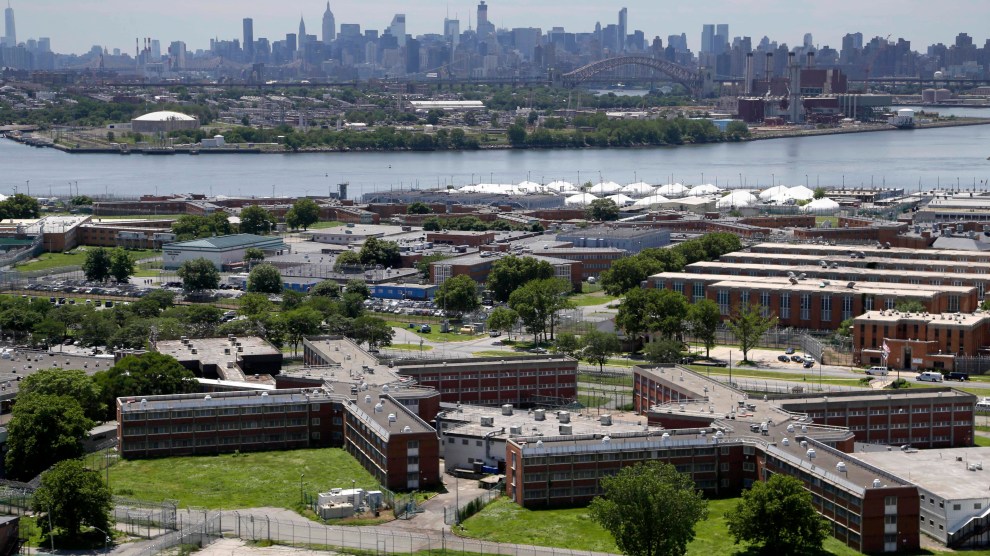

The Rikers Island jail complexSeth Wenig, File/AP

Inside a maximum-security building at the Rikers Island jail complex, Haleen, a 28-year-old man incarcerated on a parole violation, wishes he had an inhaler. At one point this week, the coronavirus was spreading through the New York City jail more than 85 times faster than the average rate of infection in the United States, according to one estimate. Haleen has asthma, which makes him especially vulnerable if he gets sick. Another guy in his unit was taken to isolation after running a high fever. “I’m praying I don’t catch it,” Haleen told me in a phone call Wednesday from the rec room, where about 20 men were watching television.

“You have officers walking around with masks—one came in today with a shower cap and a face shield and gloves, everything short of a hazmat suit,” Donald, another incarcerated man at Rikers, told me. (Attorneys for both men requested that I not publish their last names.) “And you know, we’re here with nothing.”

For weeks, the coronavirus spared US prisons and jails even as it spread through nearby cities. But that has quickly changed, and Rikers Island is at the epicenter. A week ago, on March 20, corrections officials said just one inmate at Rikers had tested positive for COVID-19; as of March 27, at least 103 inmates at New York City jails had the disease, most of them at Rikers. Public health experts are rightly concerned: People in jail are more likely to have other preexisting health conditions, putting them at higher risk for mortality from the virus. And outbreaks inside the complex will likely boomerang into the broader community, which, in New York City’s case, is already reeling from infections.

Making matters worse, inmates report a shortage of the cleaning supplies and even soap necessary to stem the spread of the virus, as many sleep in crowded, dorm-style housing units and share bathrooms, according to interviews with several people incarcerated at Rikers and their attorneys, as well as lawsuits filed by public defenders. Conditions appear to be rapidly deteriorating as jail officials impose lockdowns, delay meal schedules, and reduce access to mental health care while scrambling to deal with the pandemic. (A spokesperson from the corrections department still has not responded to my request for comment.)

On Tuesday, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced 300 nonviolent inmates would be released from Rikers to slow the disease’s spread there. But about 5,000 people are locked up in the jail complex, and public health experts say more drastic measures must be taken to keep the outbreak from growing. Public defenders are now petitioning the courts to free their clients who are still behind bars—many of whom are elderly and with preexisting health conditions. “New York cannot leave people in jails behind to suffer and die,” attorneys at the Legal Aid Society of New York City wrote in a lawsuit.

“They are not given any protection, in terms of masks,” says Laura Eraso, an attorney with the organization, who represents Haleen. “Clients are ripping their clothing and tying it around their own faces for protection, even though that wouldn’t do much. When people are suspected to be sick, they aren’t sanitizing or cleaning that person’s bed—they’re just taking that person out and putting someone else in their bed.”

As more inmates become infected, corrections officials looking for quarantine space made the rare move of reopening a Rikers facility that closed earlier this year as part of the city’s attempt to eventually shut down the jail complex. “We are using every available tool to keep people safe and prevent COVID-19 from spreading,” Peter Thorne, a spokesperson for the Department of Correction, said in a statement. But public defenders say the jail may not be quarantining enough people. In early March, the department stated that newly admitted inmates would be isolated only if they showed flulike symptoms, even though people can carry the virus for two weeks before feeling sick, or without showing any symptoms at all.

Elsewhere in the jail complex, inmates have reported varying degrees of upheaval over the past week as officials respond to the public health emergency. In a maximum-security building, Haleen has his own cell, which allows him to keep some distance from other inmates when he sleeps. But there have been other disruptions: His housing unit went on lockdown, requiring inmates to spend most of their day in their cells, likely as a precaution against the virus. On the second day of lockdown, a sewer line burst and toilets overflowed; feces and urine spewed across the floors, remaining there for more than a day, he says. When the lockdown ended, jail officials tried to slide meals to inmates under their cell doors, but the floors hadn’t been bleached. Haleen and other inmates refused to eat. “We’ve been asking for disinfectant—they don’t give us any of these things,” he says.

In a lower-security building, Donald, who is also incarcerated for a parole violation, says it’s impossible to keep the six-foot distance from other inmates that health experts recommend. He sleeps in a dorm with 60 other men, their beds just a couple of feet apart. At meals, they’re told to sit at separate tables, but they all share sinks and toilets. “Social distancing doesn’t work here,” he says. He reports that his housing unit has been out of toilet paper for days, and sometime there’s no soap. “I’m emotionally a wreck,” he told me earlier this week. “I want to get out, but my wife has asthma, my daughter has asthma. If I get it, I’m concerned I can transmit it to them.”

Some inmates have serious illnesses that could put them at risk of death if they catch the virus. One man, housed in an infirmary building on the island, recently recovered from pneumonia, but says he’s still sleeping in a dorm with 20 people and doesn’t have hand sanitizer or cleaning supplies to wipe down the phones they share. “He’s recovering from just having his lungs drained, so if he catches this, it’s fatal for him,” says Eraso, his attorney. “If I catch it, God forbid, I could be one of those people that goes out for the count,” says Philip, another man locked up on a parole violation, who is older than 50 and has hypertension and other health issues. “The anxiety level is extreme.” Kenny, 31, also locked up on a parole violation, and with asthma, puts it another way: “This feels like a death sentence.”

And for inmates who need routine medical care, nurses and doctors are in short supply. Several incarcerated men at the jail complex told me that visits with medical staffers had been postponed. “Guys will go a whole day without getting their medicine,” says Haleen, who is still anxious to get an inhaler. “I think medical staff is so inundated caring for people in quarantine and ensuring people who come down with a fever are receiving proper care that things like this fall through the cracks,” says Eraso. Dozens of correctional staffers have also tested positive for the virus, stretching the workforce even thinner.

Meanwhile, some of the hearings that would determine whether people can leave the jail have stalled. “Because of corona, guys are not being called for court; that’s making everyone go crazy,” says Haleen, whose hearing for his parole violation was scheduled for this Friday. “Are they gonna call me? If they don’t, am I gonna be stuck in here?”

Public defenders are working around the clock to free inmates at the jail, especially those who have health conditions and are locked up pretrial or for nonviolent crimes or technical parole violations. “This is something that keeps me up at night,” Melanie Robinson, another attorney at the Legal Aid Society, tells me. She has been inundated with phone calls from her clients seeking help. Some have tested positive, she says as she begins to cry.

Mayor de Blasio’s decision to release 300 people from the New York jail complex pales in comparison to the actions taken in some other places. Los Angeles has freed more than 1,700 inmates from jail early to prevent the virus from spreading. Iran let 85,000 people out of prison as a public health measure. On Friday, in response to the Legal Aid Society lawsuit, a court in New York ordered the release of about 100 more people from Rikers, including Donald, who was staying in the crowded dorm. But thousands more remain. City officials “have the power to save incarcerated people’s lives, or they have the power to take their lives,” Eraso says. “By their inaction, they will take people’s lives. It’s only a matter of time.”

The chief medical officer for New York’s jail system, Ross MacDonald, agrees. “A storm is coming,” he tweeted last week. “Please let as many out as you possibly can.”

March 30: A Department of Correction spokesperson says the jail complex has an adequate supply of cleaning products, and that all housing units provide access to soap and water and are cleaned at least once daily. The department says it has no record of a sewer line backup in the maximum-security unit a week and a half ago. “The Department of Correction is doing everything we can to safely and humanely house people in our custody,” says Peter Thorne, the spokesperson, adding that the jail complex has tried to facilitate social distancing, has implemented additional sanitation protocols, and provides masks to inmates who are in quarantine areas or who have symptoms of the virus.