Sandy Huffaker/Getty

Toward the end of a press conference on Tuesday afternoon, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis was asked about a proposal to give the state’s prisoners early access to the forthcoming COVID-19 vaccine. Polis replied that no prisoners would be prioritized to get vaccinated before the free seniors or people with coronavirus-related health risks. “There’s no way it’s going to go to prisoners,” he chuckled, “before it goes to people who haven’t committed any crime. That’s obvious.”

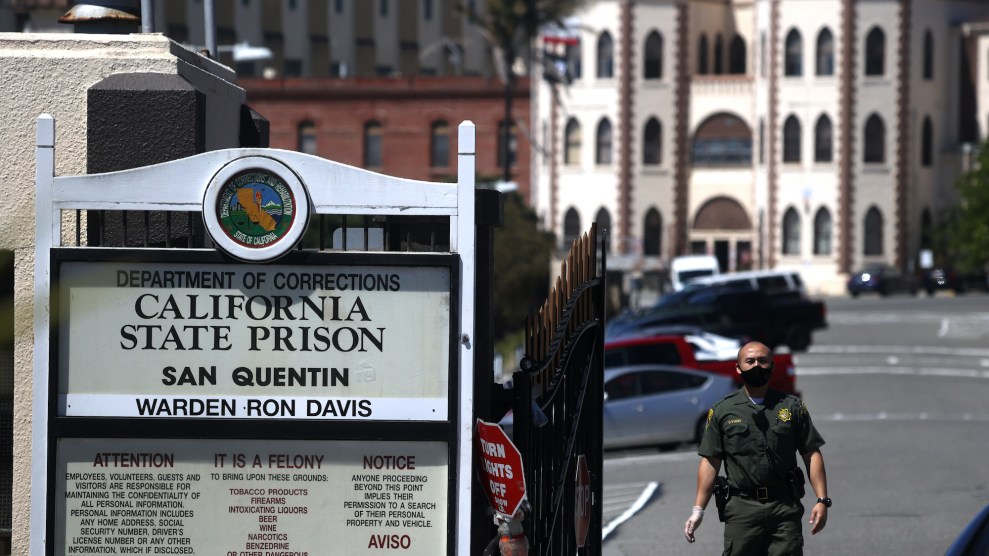

In October, Colorado’s public health department issued a draft plan that prioritized prisoners and other people in “congregate housing,” like homeless shelters and college dorms, for vaccination following health care workers, residents of long-term care facilities, and public safety personnel, including corrections officers. As in the rest of the country, prisons and jails have been the site of some of Colorado’s largest COVID outbreaks. Prisoners’ case rates are more than 550 percent higher than the state’s as a whole; rates for prison staff are 200 percent higher. The vast majority of the state’s disproportionately Black and brown incarcerated population has spent the pandemic locked up in close quarters, sharing cells, bathrooms, dayrooms, and dining halls.

As the arrival of the first COVID vaccines approaches, a political backlash has been brewing over the idea that inoculating people behind bars should be a priority. Colorado’s plan in particular has come under fire from right-wing critics. “Polis would give the life-saving vaccine to a person who puts a loaded gun to grandma’s head, before he would give it to grandma,” a Republican district attorney wrote in the Denver Post. “Killers and rapists set to get COVID vaccines before Granny,” a recent Fox News segment announced.

This pushback seems to have spooked Polis. Asked about the Denver Post column at this week’s press conference, the Democratic governor said Colorado’s public health department will deprioritize prisoners when it finalizes its vaccination plan. (Prisoners over 65, however, would likely be vaccinated around the same time as free adults of the same age.)

There is broad agreement among medical and public health experts that incarcerated people are a “critical population” for early vaccination, as the CDC’s vaccination “interim playbook” puts it. But there’s also a risk that as states finalize their vaccination priorities, they will discount the public health benefits of vaccinating incarcerated people early due to its perceived political unpopularity. “Sometimes we hear, ‘Why are we providing medical care, or doing this or that for people have committed crimes?'” says Corene Kendrick, deputy director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project. “Besides the fact that they’re human beings, and we should treat them as such, the virus doesn’t stop at the jail door.”

Last month, the American Medical Association adopted a policy that people who live and work in prisons, jails, and immigration detention centers should be prioritized to get access to a COVID-19 vaccine due to their high risk of infection. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, meanwhile, has published a framework recommending that people living and working in jails, prisons and detention centers be included in the second phase of vaccine distribution, alongside workers in high-risk settings, people in shelters and group homes, and older adults.

If states follow the recommendations approved by a federal panel of experts on Tuesday, certain elderly and sick prisoners could be among the very first people vaccinated for the virus. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices voted to recommend that top priority for the COVID-19 vaccine go to health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities. Amanda Cohn, ACIP’s executive secretary, said in an email that the latter group includes incarcerated people “living in what would be the equivalent of a skilled nursing facility.” That could be a fairly large group: The number of state prisoners who are 55 or older quadrupled between 1993 and 2013 and, as of 2015, they accounted for 10 percent of the state prison population. To care for those older prisoners, many states have built specialized units that are essentially locked-down nursing homes.

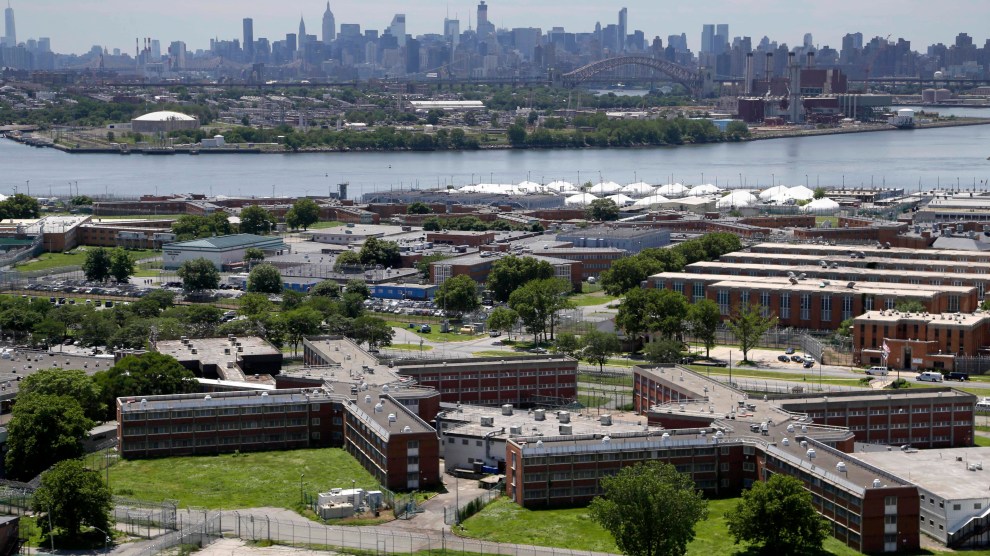

The CDC panel had considered arguments that all people living and working in jails and prisons should be included in the first tier of the vaccination schedule. “Although often considered isolated, inmates are regularly released from prisons and jails and correctional staff daily travel home to their families,” Andre Montoya-Barthelemy, a Minnesota physician investigating health hazards behind bars, told the panel during its August meeting. Without addressing these sources of infection, he said, “transmission will continue as long as the hot spots remain uncontrolled.”

David Sears, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, and a prison health consultant, concurs. “From a public health standpoint, we are not going to stop COVID-19 in the communities until we’re able to stop it in prisons and jails,” he says. According to Sears, prisoners meet the two main reasons to prioritize anyone for COVID-19 vaccination: They’re especially likely to die or suffer complications if they get sick and vaccinating them will interrupt “chains” of transmission. Prisoners’ death rate from COVID-19 is three times higher than that of the general population, controlling for age and sex. And not only can the virus spreads rapidly inside prisons and jails, they can act as a “nexus” for transmission in the wider community, Sears says, as staff members go in and out daily.

Controlling outbreaks in prisons is also important because they can overwhelm local health care systems, says the ACLU’s Kendrick. In a single California prison this summer, the coronavirus sickened nearly 2,500 people, killed 29, and sent dozens to hospitals. “They don’t have ventilators and ICUs in prisons and jail medical clinics,” Kendrick says. “They’re going to, by necessity, go to the community. And that’s a real strain.”

Last week, the Associated Press reported that the federal Bureau of Prisons is preparing to receive its first doses of the vaccine within weeks. But the initial supply will reportedly go to staff, not prisoners, potentially leaving incarcerated people exposed at the 127 BOP facilities with active cases. Similarly, the CDC advisory panel is contemplating recommending that the next priority group for vaccination include corrections officers along with other essential workers.

Sears believes vaccinating corrections staff first could create “at least some ring of protection” for people inside, but it isn’t enough, especially if prisoners with high-risk medical conditions aren’t also considered a priority. “My greatest fear,” he says, “is that with each little, small trickle of doses that come out, that correctional facilities just get bumped down to the next tier and bumped down to the next tier. There is, unfortunately, a strong historical precedent for ignoring the rights to health and health care of incarcerated residents.”