A woman pays respect to George Floyd at a mural at George Floyd Square in Minneapolis.Julio Cortez/AP

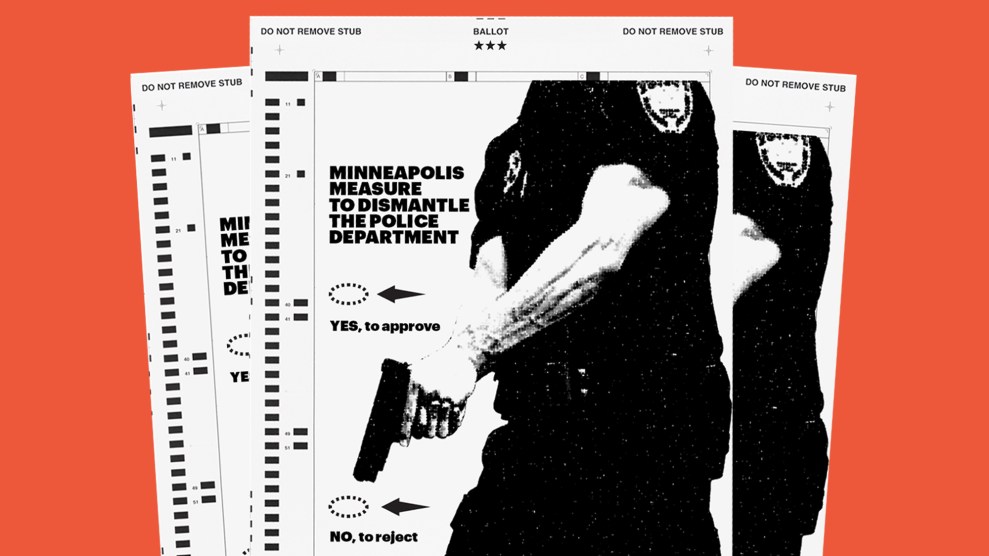

Nearly a year and a half after a white Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, voters in the city have decided not to replace their police department with a new public safety agency that would have relied less on armed officers.

Fifty-seven percent of voters rejected the proposed Department of Public Safety, which would have likely included a smaller number of cops, along with unarmed social workers, violence interrupters, traffic safety responders, and homeless outreach coordinators who would have tried to prevent crimes by helping people access housing, jobs, education, and health care. The election was seen in some ways as a test case for the movement to reimagine public safety and reduce funding to traditional law enforcement.

“We all agree that we can’t sustain as we are now with the way policing has been,” Brian Herron, the pastor of a church on the city’s North Side and an opponent of the ballot measure, told the New York Times. But he added that dismantling the police department made him nervous because he worried about crime. “We don’t have time to reimagine. We got bodies dropping in the streets. We got innocent folk being killed.”

The question of whether to create the new public safety agency deeply divided the city: In one September poll, 49 percent of residents favored the ballot measure, while about 41 percent did not. Rep. Ilhan Omar, who represents Minneapolis in Congress, and Keith Ellison, the state attorney general, both supported the measure. Minnesota Sens. Amy Klobuchar and Tina Smith did not.

Voters in Minneapolis are also deciding whether to reelect or replace Mayor Jacob Frey, who has faced intense pressure from progressive organizers over his stance on policing. Frey, a Democrat, also opposed the ballot measure to create the new public safety agency, arguing that the city could not safely reduce its police force at a time when gun violence has risen locally and around the country. The outcome of the mayoral race was not yet clear when the results of the public safety ballot measure were announced Tuesday night; 17 candidates are vying for the position.

Since Floyd’s death, Minneapolis has become a focal point in the national conversation around how to reimagine public safety, as progressive organizers across the country press officials to downsize or defund police departments. Hundreds of volunteers went door to door in Minneapolis to share information about their proposed Department of Public Safety, and out-of-state donors chipped in to the cause: The DC-based Open Society Policy Center, the lobbying arm of the Open Society Foundations founded by billionaire George Soros, gave Minneapolis organizers $500,000 for their canvassing.

Along with creating a new public safety agency, the ballot measure would have amended the city’s charter, removing a provision that requires officials to fund a minimum number of police officers. Supporters of the measure wanted to make the number of cops more proportional to the percentage of 911 calls that require an armed response. A study last year of 10 cities around the country (not including Minneapolis) found that only about 1 percent of calls for police service were related to serious violent crimes. Other calls might instead be handled by substance abuse counselors, paramedics, or other medical workers.

Opponents of the ballot measure worried that the public safety agency would leave communities more vulnerable to gun violence, which has surged during the pandemic. According to recent estimates from the FBI, homicides rose 30 percent last year across the country, largely because of shootings in under-resourced neighborhoods of color.

In Minneapolis, a group of residents on the North Side sued the city last year over police staffing, arguing there weren’t enough officers to keep people safe. The pro-police group All of Mpls, led by Steve Cramer of the Minneapolis Downtown Council, raised more than $100,000 to campaign against the ballot measure. “It is a major challenge,” Steve Fletcher, a Minneapolis City Council member who supported the public safety agency, told me recently. “Anytime you try to change the system of policing, the first time anything goes wrong, the first time there’s a crime, there are people who point to that and say, ‘You see, we need police.’”

But the idea that ramping up police presence is the best way to improve public safety continues to be debated. As I recently explained in a piece debunking myths about crime, the uptick in shootings last year was widespread, including in municipalities led by Republicans that gave police departments more money.

And in some ways, the fact that 43 percent of people voted to dismantle and replace the police department is a sign of shifting attitudes. “While this is not the result that we hoped for, the story of our movement must be told,” Corenia Smith, who helps lead Yes 4 Minneapolis, a coalition of activists that canvassed in support of the Department of Public Safety, said in a statement. “We changed the conversation about what public safety should look like…Now we will work to hold leaders and the system accountable. We will work to heal our city and create safer streets for all our communities.”

This article has been updated.