<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FEMA_-_13316_-_Photograph_by_Bill_Koplitz_taken_on_06-21-2005_in_Virginia.jpg" target="_blank">FEMA</a>/Wikimedia

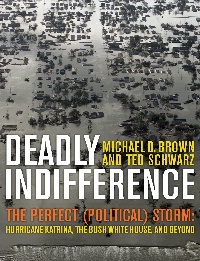

For all the Bush administration’s failures in handling Hurricane Katrina, only one person was made the poster boy for the catastrophe: Federal Emergency Management Agency head Michael Brown. Even as George W. Bush was praising him for doing a “heckuva job” in the response, Brown was on his way out; the floodwaters had barely receded when he submitted his resignation. He was later lambasted when emails he sent at the height of the storm came to light; they included lines like “Can I quit now? Can I go home?” and chatter about his clothes. But in the years since, Brown has been on a mission to clean up his image. His latest venture is a health care technology firm, Apokalyyis, Inc., and he has a new book out offering his own take on what went wrong in the wake of the worst hurricane ever to hit the US.

Deadly Indifference is one part apology and two parts passing the blame. While Brown does accept fault for the mishandling in some respects, like not being as attentive to some response details as he perhaps should have been, he spends much of the book pointing his finger up the chain of command, from others at a Department of Homeland Security mired in bureaucracy to a commander-in-chief who couldn’t be bothered to take time away from his Crawford vacation to visit the shattered Gulf region. The book’s revelations range from the not-so-revelatory—he feels he was “made the scapegoat”—to accusing Karl Rove and Trent Lott (among others) of capitalizing on the storm for political gain. Katrina “was the first time in 160 disasters that I kept smelling politics,” Brown, whose jobs since leaving the administration have included serving as a disaster-preparedness consultant and talk-radio host, told Mother Jones. “It was something I never saw anywhere else.”

One might ask why Rove had anything to do with the Katrina response at all. And that would be a good question. “Karl Rove became interested in Louisiana for the very practical reason that it had voted solidly Democratic when Bill Clinton won his two terms, and it had voted for George W. Bush in the election that followed,” writes Brown. Basically, the state had a large swath of the registered voting population that didn’t have a strong alliance to either party. Gov. Kathleen Blanco was the first female governor of the state and the first Democrat to be elected in more than a decade. New Orleans’ mayor, Ray Nagin, was a Republican before changing parties in 2002. The storm, Brown asserts, presented a “wonderful opportunity to bring Louisiana solidly with the Republicans.”

In a recent interview on ABC News, Brown accused Rove of “micromanaging” search and response efforts—stepping in and making specific requests of FEMA resources to help those identified as allies, “totally irrespective of what the overall game plan was to respond to this disaster.”

In an interview this week with Mother Jones, Brown walked back from the term “micromanaging,” but maintained that White House interference was a large part of the problem. “Now you have three-way communications going on, which make it even more difficult to make decisions and sometimes even end up making conflicting decisions,” Brown says. He has claimed to have emails from the White House demonstrating this and has said he would share them, but has not, so far, made them available.

The subject of the most scorn, though, is then-Sen. Trent Lott of Mississippi (R). The book’s most damning passages refer to his desire to move the USNS Comfort, the Navy’s medical treatment ship, to Pascagoula, Miss., rather than to New Orleans where it was needed most. Lott, one will recall, had resigned as Senate Minority Leader in December 2002 amid controversy over his remarks about Strom Thurmond, and was enjoying less political clout than he’d once held. He wanted the Comfort in Mississippi, Brown writes, simply for the “damn photo opportunity,” and was indifferent to “any reality other than his political ambitions.”

Late at night, as the Comfort was heading to New Orleans, Lott called Brown demanding that he change its course, Brown writes. “WHY DON’T YOU GROW SOME BALLS AND BE A REAL MAN?” Lott screamed, according to Brown. When Brown refused, Lott went over his head to Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff, who capitulated. This kicked off, in Brown’s words, a “full-scale clusterfuck.” The Comfort was redirected to Mississippi, and in the ensuing confusion no ships were sent to New Orleans—whose residents were desperate for shelter and medical attention.

Brown also pegs Dennis Hastert (R-Ill.), then Speaker of the House, for wanting a FEMA employee assigned to each member of Congress from the region—another political move, he says, to create the appearance of doing something rather than actually serving a purpose. Brown doesn’t spare a lot of kind words for fellow Republicans (or Democrats, for that matter, specifically Nagin and Blanco). Bush, while described as a “decent man,” is also deemed negligent at best—but generally indifferent when it came to Katrina.

While the book jacket promises that Brown won’t be “making excuses,” it’s hard to find many points in the book where he admits his own errors. Perhaps that would dampen his efforts to rehabilitate his own image. In our conversation, the best he could come up with for what he would handle differently is the “communication” side of the story—specifically, how he dealt with the press. He’s certainly counting on the book to recast his public persona. In the very least, it reaffirms that there was plenty of blame to go around, both inside and outside of the Bush administration.