The village of Thule in northwestern Greenland. <a href="http://belzebub2.com/gallery?lang=en">Belzebub II</a>

This story first appeared on The Atlantic website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Every winter, like clockwork, the sea ice that covers the Arctic thickens and grows. And then every summer, the earth tilts its Northern Pole toward the sun and some of that ice melts away.

But not all of it. Even in the summer months, many of the northern channels and passages that connect the Atlantic to the Pacific are blocked off by ice. For centuries European explorers searched for a passage unsuccessfully, until 1906 when an expedition led by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen made it across. Since then, better boat and navigation technology have enabled more regular crossings, but the most northern routes have remained off-limits for all but the strongest, diesel-powered, extra-fortified, ice-breaking boats.

Until this year, when three men made the complete Northwest crossing through the M’Clure strait (the northernmost of the direct routes) in the Belzebub II—a sailboat with no fortification. Previously, the only boats that had made it through M’Clure were ice breakers, and none had been able to complete the pass through Viscount Melville Sound after shooting through M’Clure. Usually only either the sound or the straight are open to boats, but not both at once.

“This year, the fact that both were melted at the same time, and that we were able to sail through on our 31-foot fiberglass boat that’s not reinforced for ice (and even if it was, it wouldn’t do anything), is quite telling of the change taking place in the Arctic at the moment,” Nicolas Peissel, one of the three crewmembers, told me on Skype from a supermarket in Nome, Alaska, where the ship was last week.

Those changes? This summer’s unprecedented sea ice melt.

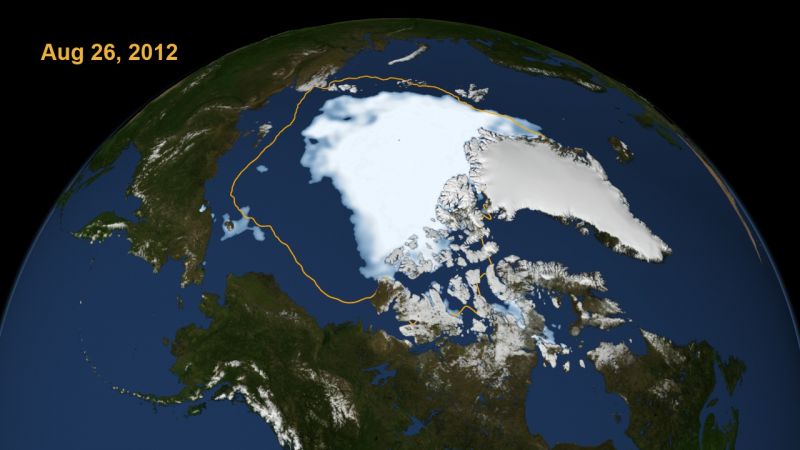

In August, the Arctic sea ice shrank to a smaller patch than at any other time humans had recorded. At the time, Alexis Madrigal wrote, “It’s only late August, several weeks before the traditional time when the sea ice melting stopped. That could mean that the melt is stopping earlier and could begin to recover earlier. Or we may have several weeks to go of melting, in which case, this year’s low could not just break but shatter 2007’s record. “

And that latter scenario is precisely what happened. Last week, the National Snow and Ice Center announced that the sea ice cover bottomed out at 1.32 million square miles—nearly 300,000 square miles fewer than the prior record, set five years ago in 2007. The lowest six years on record have all taken place over the last six years. In the next four years, the summer ice may collapse completely.

“There’s really nothing like what we’ve seen happen this year,” says Dr. Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University in the video below. She continued, “This is a big problem. This is a real problem. It’s happening now. It’s not happening generations from now.” The video, from Yale’s Forum on Climate Change and the Media, does an excellent job showing the trajectory of the change over recent years, and explaining how changes that have already happened, will bring about greater and greater changes in the years ahead.

For Peissel and his crewmates (his cousin Morgan Peissel and his friend Edvin Buregren), this melt presented the opportunity to sail on through, partly in the name of adventure, but more so, in the name of bringing more attention to climate change and how it is reshaping the topography of our planet. Last year they sailed from Sweden to Scotland to Greenland to eastern Canada, mostly to test how the boat fared in ice. They spent last winter preparing for their trip, and set off in June from Newfoundland.

In June, July, and August, they sailed north along Greenland’s western coast, until they reached Qaanaaq, also known as Thule, in northwestern Greenland. “This is pretty much the highest you can go on the Greenland coast, and the last village that you can stop at,” Peissel told me.

“We sailed a little farther north than that, and we reached 78 degrees latitude where we were stopped by the polar ice cap. It was a wall of ice,” he continued. A few days later they reached Grise Fiord—Canada’s northernmost settlement—where they stayed for a few days and learned about how the Inuit population there lives. From there they headed south, sailing across the Lancaster Sound until they reached Resolute, a community in the Canadian territory of Nunavut. Most people making the Northwest Passage normally head south at that point, through Peel Sound to Gjoa Haven and then to Cambridge Bay. “That is the traditional Northwest Passage,” Peissel said. “That’s what most people have done. I think there’s been 140 boats or something who have done it in history, and that’s ice breakers, sailboats, ice-strengthened ships, cruise ships, or whatever. They do the southern route. So still very few people have done the southern route. But we wanted to do the northern route through Viscount Melville and M’Clure.”

Resolute, Canada. (Belzebub II)

They waited in Resolute until just the right moment. Viscount Melville was closing up very quickly, but there was a clearing, enough so that they thought they could make it through. They rushed through so that they would be ready to take on M’Clure if it were to open. They made it through, but because of an equipment problem they had to turn around to Resolute, where they spent a week waiting for parts. (You can see this turnaround in the map at the top.)

They planned to get across Viscount Melville and anchor in the Prince of Wales Strait, where they would wait for up to two weeks for a good opening in M’Clure. But, as soon as they arrived Ice Services Canada sent them a report saying there was a two- to five-mile-wide channel following the northern shore of the island. “This was absolutely huge for us,” Peissel said. Nevertheless, Ice Services Canada strongly advised them not to go. They told them that the winds were going to shift, pushing huge pieces of ice southward and closing the channel. “But,” Peissel recalls them saying, “if you were to try this, you probably have a 48-hour window.”

They set sail, hugging the coast, right along the cliffs on the north of Banks Island. “It was land on one side, ice on the other,” Peissel described it.

When they were not even 12 hours into the stretch (a third of the way) when they learned that the ice was closing up behind them. It was impossible to turn around. They had “nowhere to go but forward.” Peissel says, “We became quite nervous. If the rest of the ice had sealed us in, we would have certainly had to spend the winter in the Arctic.” Their supplies, he said, were “probably insufficient.” The plan would have been to freeze the boat in, trek to the nearest community (which was about 500 miles away), and they would have chartered a flight in to pick them up. He says they would not have called the Coast Guard for help, knowing they were responsible for having put themselves at risk.

The next report from Ice Services Canada did not provide better news: The ice was closing in ahead of them as well. In about five hours, they would reach a point where a thick band of ice was pushing up against the land—ice so thick that their boat would not be able to go through. With no other choice, they continued along, and, miraculously, when they reached that spot, the ice was much thinner than they had expected. Not long after, “We sailed out into open waters the wind and seas died immediately transforming the churning sea to a peaceful place allowing us to travel south quickly to the Arctic Circle,” they wrote on their blog.

This journey would have never been possible in earlier summers, Peissel says. In preparing for the journey, he printed out and studied nearly every ice chart of every week of the summer months since 2000, and there are three years when both M’Clure and Viscount Melville open—2007, 2010, and 2011, he believes. In those three years they did both open, but they opened too late in the season, so late that no one was still sailing in the Arctic in any sort of pleasurecraft.

Peissel echoed to me something Jennifer Francis says in the video above: You do not need to be a scientist to see the environmental change in the climate. The ice melt is on a scale so large that you can see it not just in the charts of year-after-year scientific measurements, but right in front of you from the bow of your ship.