Illustration: John Hersey

The fast-food marketing wizards are at it again. Popeyes recently introduced Dip’n Chick’n—fried chicken pieces shaped to better spoon up sauce. Not to be outdone, McDonald’s has come out with Chicken McBites—this one in a “container that fits in a car’s cup holder with a slot for dipping sauce,” the Wall Street Journal reported.

Although Americans’ meat consumption has dropped in recent years, we still eat more meat per capita than any other nation (except tiny Luxembourg). And many consumers know that our meat habit is a major contributor to heart disease and deforestation. But it’s even worse for something few people think about when they pull up to a drive-thru: the oceans.

The marine world is one of our oldest sources of sustenance. In his 2012 book The Ocean of Life: The Fate of Man and the Sea, British scientist Callum Roberts marshals strong evidence to argue that our leap from ape to larger-brained Homo species was driven by access to coastal shellfish, which are rich in brain-boosting omega-3 fatty acids. Now we’re close to polishing off that feast. In a landmark 2006 study in the preeminent journal Science, a global team of researchers found an “ongoing erosion of diversity” in sea life that, if left unchecked, would lead to the collapse of all fisheries by 2048. The situation is barely improving. I recently spoke with one of the paper’s authors, ecologist Boris Worm of Canada’s Dalhousie University. “The loss of [oceanic] biodiversity continues at a pace that’s not slowing down,” he said. “On average, the condition of the oceans continues to get worse.”

What does that have to do with deep-fried chicken scraps? The answer lies in what we feed the billions of farm animals we raise and consume each year. Corn and soy, which supply most factory farm feed, are grown with intensive use of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers. In the Gulf of Mexico, runoff from Midwestern fields feeds a Beijing-size dead zone each year, a massive algae bloom that blots out sea life in what should be one of the globe’s most productive fisheries.

Over in the Chesapeake Bay region, 523 million chickens generate 42 million cubic feet of waste each year, the Pew Environment Group reports, enough to fill the Capitol dome 50 times over. The result is a recurring dead zone that spans from Baltimore Harbor to south of the Potomac River.

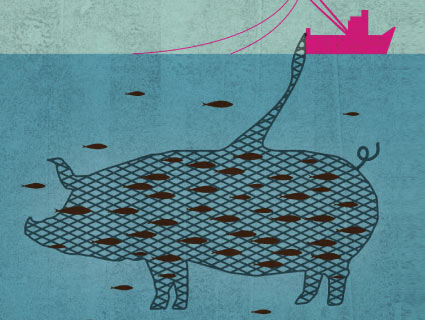

But the connection between cheap meat and the decline of the oceans runs even deeper. The livestock we eat can’t be sustained on corn and soy alone, and that’s where we run into what I’ll call the anchovy problem. Every year, about a third of all the fish humans pull out of the ocean consists of small species known as “forage fish”—anchovies, sardines, and other oily fish that feast on plankton and are in turn feasted on by larger fish. An astounding 90 percent of the forage catch is ground into fish meal and fish oil, and at least a third of that is devoted to feeding chickens and pigs.

When we pull huge amounts of forage fish out of the oceans to meet livestock’s protein needs, we leave their predators—top-feeding species like sharks, tuna, and salmon, as well as a range of seabirds—wanting. According to a recent report by respected marine and fishery scientists, three-quarters of the oceans’ major ecosystems contain at least one predator that relies on forage fish for half of its diet.

Ultimately, those scientists concluded, keeping those predators alive and thriving is worth more to humanity than keeping fish meal flowing to factory farms. Just as cows can convert something humans can’t digest—grass—into high-quality digestible protein, forage fish are the key pivot of the oceanic food chain. They eat tiny sea organisms that, say, sharks can’t, and in turn become the primary food for a dizzying array of larger species. Take them away, and those larger species suffer—and fisheries decline, meaning less fish for us to eat. On the East Coast, overfishing of a small, bottom-feeding fish called menhaden has resulted in a population nosedive of 88 percent in the last 25 years. About four-fifths of all menhaden caught go to fish meal.

What’s an ocean-loving snacker to do? The answer isn’t “buy organic chicken”—even those birds are fed fish meal. Instead, consider this: It takes about two pounds of feed to produce a pound of chicken—instead, we could eat those two pounds of plants in the form of falafel, that delicious, ancient convenience food based on chickpeas. (Indeed, in Egypt, McDonald’s has carried the McFalafel.) When you crave protein of the animal variety, consider forage fish, rather than the chicken that ate them. In southern European countries like Portugal and Spain, bars serve grilled sardines so regularly that they almost qualify as fast food. Dip’n Sardines, anyone?