Exxon's new climate report says the company plans to extract all its proved fossil fuel reserves. J. Scott Applewhite/AP Photo

ExxonMobil has 25.2 billion barrels worth of oil and gas in its current reserves, it’s going to extract and sell all of it, and isn’t expecting any meddling climate regulations to get in the way.

That’s the main takeaway of a report the company released this week to its investors, examining the risk that greenhouse gas emissions rules in the US and worldwide might pose to its fossil fuel assets. Exxon made headlines a couple weeks back when it promised to issue the report after facing pressure from shareholders led by Arjuna Capital, a sustainable wealth management firm.

If stricter limits on carbon pollution or high carbon taxes force energy companies to keep their holdings buried underground, the thinking among environmental economists goes, it could topple the companies’ value and leave investors holding the bag. The result, economists warn, would be a collapse of the so-called “carbon bubble.”

Some big energy companies (including Exxon) have already nodded to this problem, by building a theoretical carbon price into their projected balance sheets. But this report is the first time a large oil and gas company has published a detailed assessment of its own climate risk exposure, according to the New York Times.

The report doesn’t present a very optimistic view of the prospects for aggressive climate action by world leaders.

“We are confident that none of our hydrocarbon reserves are now or will become ‘stranded’,” the report says. “Stranded assets” is a term climate economists use to refer to fossil fuel reserves that could be stuck in the ground if countries around the world implement sufficiently stringent carbon regulations to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels—a threshold agreed to at the 2009 UN climate summit in Copenhagen. The amount of carbon humans can release without exceeding this limit—roughly 485 billion metric tons of carbon beyond what we’ve already emitted—is often called the “carbon budget.”

Exxon’s report suggests that its planners don’t believe serious carbon limits will be on the books anytime soon, leaving the company free to burn through its reserves of oil and gas. That’s a disconcerting vision to come just on the heels of Sunday’s new Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, which predicted a nightmarish future if greenhouse gas emissions aren’t slowed soon.

“The reserves are going to be able to turn into money, because they’re assuming there isn’t going to be a policy change,” said Natural Resources Defense Council Director of Climate Programs David Hawkins. “They’re definitely saying that no matter how bad it gets, the world’s addiction to fossil fuels will be so overwhelming that the governments of the world will just suck it up and let people suffer.”

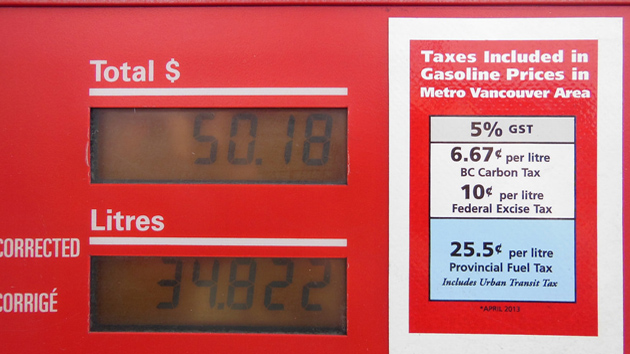

In other words, Exxon’s report finds, no matter what happens with climate change, the economics of fossil fuel production are likely to stay favorable for the foreseeable future. The price of carbon would need to rise past $200 per metric ton by 2050 to make burning it so expensive that greenhouse gas concentrations would level off at 450 parts per million, according to the report. That’s orders of magnitude beyond the roughly $9 price that currently exists in Europe’s cap-and-trade market. The price is a little higher in British Columbia, where it’s set by a carbon tax, but even there it’s nowhere near the $200 threshold.

So just how much fossil fuel is Exxon sitting on? Government filings show that at the end of last year, the company’s total proved reserves were the equivalent of 25.2 billion barrels of oil, which the report says the company will go through in the next 16 years. (This doesn’t mean they’ll run out of reserves at that time; the amount of proved reserves changes frequently as the company adds more to their holdings all the time.) But just that amount—from one company in a limited timespan—could produce carbon emissions equal to roughly half a percent of the total remaining budget for all carbon emissions for the rest of time, if we’re to keep the planet within the agreed-upon warming limit.

That’s a pretty scary outlook, but Hawkins cautioned not to read too deeply into the report, which comes with a caveat that the way things will actually pan out in the future “could differ materially” from what’s presented in the report. In other words, Exxon isn’t bound to anything presented here. If the IPCC’s latest predictions for climate impacts hold true, the kind of fossil fuel restrictions Exxon is hoping to avoid could still be in the offing as governments take steps to intervene.

“They may have convinced themselves that this is a reasonable scenario,” Hawkins said. “But I think they’re absolutely wrong.”