Grand Cayman Island is a speck of white sand about twice the size of Manhattan floating in the Caribbean Sea halfway between Cuba and Belize. It’s known mainly as an offshore tax haven—”Wolf of Wall Street” Jordan Belfort spoke to a gathering of business leaders there recently—and as a stopover for cruise ships packed with sunburned Americans sipping bright blue cocktails with paper umbrellas.

It’s also a key haven of marine biodiversity, sporting 36 different coral species (corals are tiny animals that build rock-like reef structures) and 350 kinds of fish. Generally speaking, coral reefs are some of the most ecologically rich habitats on Earth, supporting 25 percent of marine life in less than one percent of the ocean environment. They’re a first line of defense for coastal communities against devastating storm surges. In Cayman, as in many small island nations, reefs are the backbone of the local tourism and subsistence fishing industries. And they’re rapidly dying off.

A study published last October found that on reefs around Little Cayman, a kind of suburb island adjacent to Grand Cayman, coral cover fell from 26 to 14 percent just between 1999 and 2004. Since the early 1980s, coral cover across the entire Caribbean has plummeted 80 percent, so that living corals now cover only 10 percent, on average, of available surface area. And a 2011 report from the World Resources Institute that labeled reefs around Grand Cayman as highly threatened found that what’s happening there is a microcosm of a global trend: 90 percent of the world’s coral will be at risk of disappearance by 2030, thanks primarily to ocean acidification and global warming, both products of greenhouse gases released by human activity.

Tim Austin, an ecologist with the Cayman Department of Environment, has seen this transformation first-hand. In April, Austin, who was born and raised on Grand Cayman, took me on a snorkeling trip to some of the island’s hardest-hit reefs (watch the video above for an under-the-waves tour). He recalled that as a kid it was nearly impossible to navigate boats into docks because of the dense forest of living coral just below the surface.

“Anybody who’s been diving in Grand Cayman for a long time would agree that it’s very different today,” he said. “But it’s a very slow death. These things are dropping apart and no one is really aware of it.”

When I jumped off the boat with Austin, I expected to see a postcard-perfect scene with mounds of vibrantly-colored coral. Instead, the ocean floor looked like a boneyard. When corals die, they leave behind a calcium carbonate skeleton, known as a “framework,” that retains the basic shape of the reef but with the bright colors of the living coral faded out. (The colors come from symbiotic algae, called zooxanthellae, that live inside the corals’ cells and photosynthesize sunlight to produce nutrients the corals need.) Living corals stood out here and there, and fish darted from one to the next.

So what’s causing the die-off? Corals everywhere are fragile and obviously unable to run away from adverse conditions; they can be smashed by severe waves and boats and poisoned by polluted runoff from the land. Overfishing is a major problem; fish graze on the algae that live on reefs, keeping it trimmed down and allowing sunlight to reach the zooxanthellae. Without help from the fish, the coral get out-competed by the algae and can die. Austin said his office is in a constant battle to keep people from fishing algae-grazers, and the government recently passed a sweeping conservation law that will set aside up to half of the island’s coastal waters as no-fishing zones for this reason (only about 15 percent are so designated today).

More importantly, corals are squeezed between two impacts of rising greenhouse pollution that local officials like Austin are powerless to regulate: Ocean acidification and warming. The oceans absorb roughly a third of humans’ carbon emissions. By mid-century, this will make surface waters worldwide twice as acidic as they were prior to the Industrial Revolution, according to NOAA. Acidic water can erode the corals’ framework and impede their ability to reproduce.

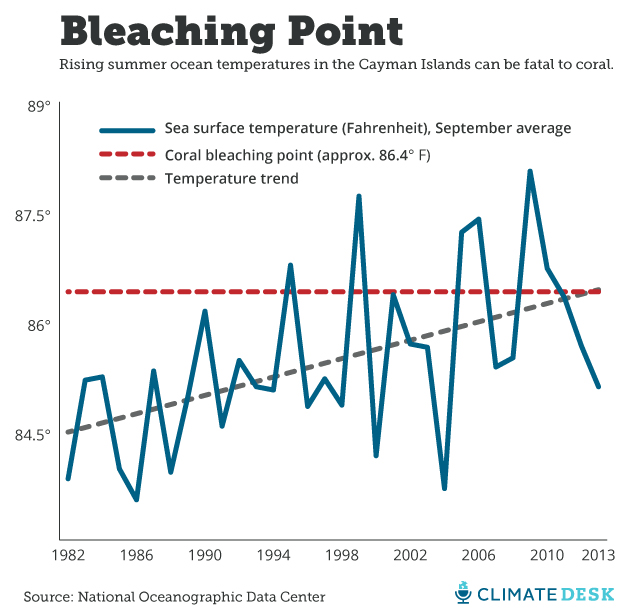

Meanwhile, warming ocean water pushes the corals closer to the “bleaching threshold”—roughly 86.4 degrees Fahrenheit in the Caribbean. That’s the temperature at which heat stress causes a coral to spit out its zooxanthellae, a move that is usually fatal. (One biologist I spoke to compared it to a person having a massive heart attack without medical attention). The graph below shows average sea surface temperatures at Grand Cayman for the month of September, typically the island’s warmest month, when coral are most at risk. The last peak on the graph corresponds to the island’s last major bleaching event, in 2009, when widespread bleaching was documented nearly 200 feet below the surface. The last few Septembers haven’t been quite as extreme, but the trend is clearly going up; in fact, NOAA data indicate that 2014 is already shaping up to be one of the warmest years in over a decade.

The silver lining to bleaching events is that they allow conservation-minded scientists like Austin to gauge the effectiveness of local protective policies; after the 2009 event, local scientists found that coral cover was roughly seven percentage points higher—and suffocating algae 14 points lower—inside protected no-fishing zones. Having a healthy fish population helped the coral better cope with warming water; in other words, local conservation provided an effective roadblock against global climate change.

More good news: Last month, new evidence emerged that corals may be able to adjust over time to warmer waters, in effect raising the bleaching threshold. In a study published in the journal Science, marine biologist Stephen Palumbi of Stanford University found that corals placed in warm water baths were able to adjust to the new conditions in a matter of years, not over multiple generations as previously thought. Some species fared better than others, and Palumbi suspects these species may have unique genes that account for the difference; he’s currently working to identify the genes so they can be bred into other species and then used to seed climate-resistant reefs.

But Palumbi cautioned that both the speed at which warming is taking place and the unprecedented highs it could reach might prove too much for even the hardiest corals.

“The question is how far can they go, and will they poop out?” he said. “I don’t think they’ll be able to keep up with us.”