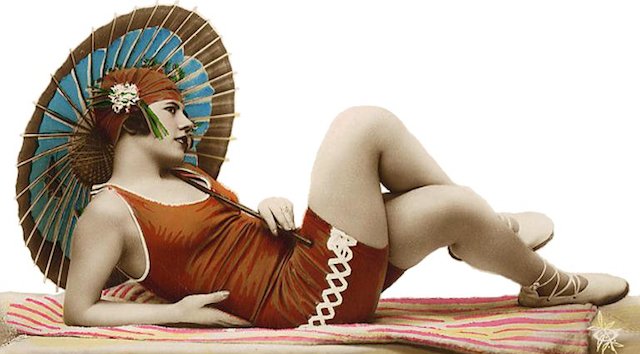

1920s bathing suit <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swimsuit#mediaviewer/File:BathingSuit1920s.jpg">Wikimedia Commons</a>

These days, drinking more water seems to be the solution for everything from weight loss to youthful skin. In fact, we’ve taken our obsession with water so far that the medical community is actually warning people that drinking too much water can be poisonous. What most of us take for granted, however, is that water (in reasonable quantities) is safe to drink—a notion that was absolutely not true 100 years ago.

The innovations that gave us clean drinking water don’t seem as sexy as self-driving cars or a rover on Mars. But author Steven Johnson argues that these types of technological advances have changed our world in profound ways—impacting everything from life expectancy to women’s fashion (more on that below).

Seemingly mundane scientific breakthroughs can create what Johnson calls a “hummingbird effect,” a reference to the great evolutionary leap that species made when it began to mimic the flight patterns of insects in order to extract nectar more efficiently from flowers. Johnson coined the phrase while writing his latest book—How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World—in Marin County, California, where hummingbirds were frequent visitors in his garden. What started out as a distraction provided him with an apt metaphor for the often unpredictable and far-reaching effects that a simple innovation can have on society. “You think you’re inventing something that just involves flowers and insects, but it ends up changing the anatomy of birds,” says Johnson on this week’s episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast. “We see that again and again and again in the history of technology.”

So how does Johnson link clean drinking water with female fashion? The story begins with a 19th-century problem. As American cities grew larger, contamination of drinking water by sewage was becoming a serious health hazard. For John Leal, a doctor based in New Jersey, the problem was personal: His father had died a slow and agonizing death after drinking contaminated water during the Civil War. He wasn’t alone. “Nineteen men in the 144th Regiment died in combat,” writes Johnson, “while 178 died of disease during the war.”

In addition to his work as a physician, Leal was a health officer and inspector for the city of Paterson, New Jersey. His duties included understanding and curtailing communicable diseases and disinfecting the homes of people who died from them. He was also in charge of the city’s public water supply and the safe disposal of sewage. This combination of interests and responsibilities ensured that he spent a lot of time thinking about how to improve water safety. Whereas other doctors rejected the notion of using chemicals to kill noxious bacteria in water, Leal began to consider chlorine—in the form of calcium hypochlorite—which was commonly used to disinfect houses and neighborhoods affected by typhoid and cholera outbreaks.

Chloride of lime, as it was called back then, smelled terrible and was known to be toxic, so the idea of putting it in drinking water seemed ludicrous. But Leal realized that in small doses, it was essentially harmless to humans and yet still effective at destroying deadly bacteria. “Leal understood [this] in part because he had access to very good microscopes,” explains Johnson. “In the old days, if you had a hypothesis about how to clean the water, you would kind of do it, and then you’d wait for a month and see if anybody died.”

But putting what is essentially poison into the city’s water supply was still an unpopular suggestion, to say the least.

And so, a few years later, when Leal was put in charge of Jersey City’s water supply, he added chlorine to the city’s reservoirs “in almost complete secrecy, without any permission from government authorities (and no notice to the general public),” writes Johnson. And not surprisingly, once people realized what he had done, Leal was called a madman and even a terrorist. He had to appear in court to defend his actions, where he testified that he believed his chlorinated water was, in fact, the safest in the world.

The case was settled in his favor and, unlike many of his contemporaries, Leal gave away the recipe for chlorination for free to whomever wanted it. “Unencumbered by patent restrictions and licensing fees,” writes Johnson, “municipalities quickly adopted chlorination as a standard practice, across the United States and eventually the world.”

Mass chlorination had some predictable effects, reducing the mortality rate in the average American city by 43 percent. According to Johnson, parents of infants benefited even more significantly, as the death rate for babies dropped by 74 percent. And while reducing mortality is perhaps the most important consequence of Leal’s innovation, there is also a lighter side to the story.

As World War I came to an end and chlorination spread across the country, some 10,000 public baths and pools were opened in the United States, giving women a new forum to show off their figures. As pools became safe and swimming became the norm, swimsuit fashions exploded. Or compressed, more accurately. “At the turn of the century,” Johnson writes, “the average woman’s bathing suit required 10 yards of fabric; by the end of the 1930s, one yard was sufficient.”

“Hanging out at a pool and seeing people in swimsuits” became a major driver of fashion, says Johnson. And while Hollywood glamor, fashion magazines, and other cultural changes had an effect, “without the mass adoption of swimming as a leisure activity,” he writes, “those fashions would have been deprived of one of their key showcases.”

How We Got to Now‘s publication also coincides with a six-part PBS and BBC television series airing Wednesdays at 10 p.m. EDT, from October 15 to November 12. You can watch a preview below:

Click here to listen to our full interview with Steven Johnson:

Inquiring Minds is a podcast hosted by neuroscientist and musician Indre Viskontas. To catch future shows right when they are released, subscribe to Inquiring Minds via iTunes or RSS. We are also available on Stitcher. You can follow the show on Twitter at @inquiringshow and like us on Facebook. Inquiring Minds was also singled out as one of the “Best of 2013” on iTunes—you can learn more here.