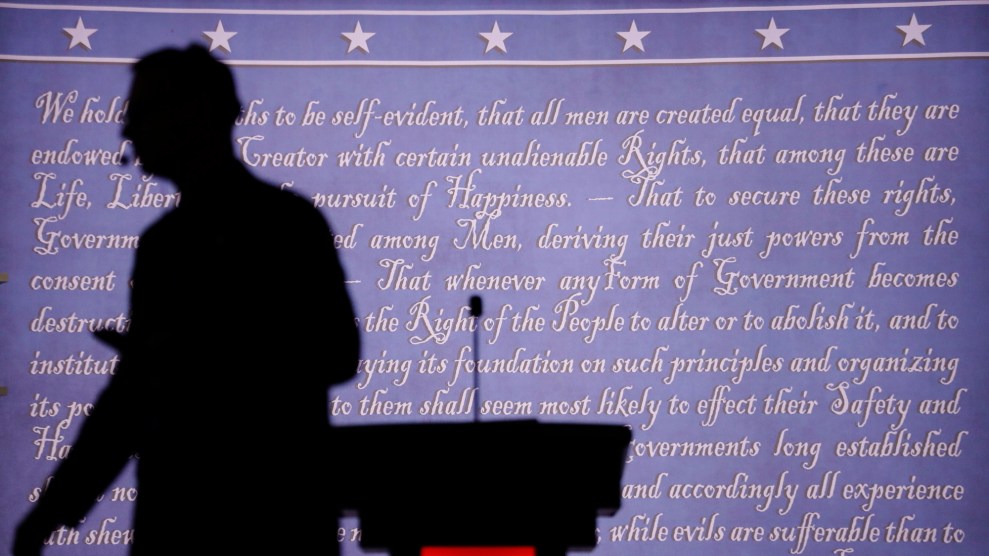

No questions about climate change were asked at last week's presidential debate.David Goldman/AP

It’s been nearly eight years since American presidential candidates were last asked about climate change during a general election debate. Lester Holt didn’t ask Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump about the issue when they met last week at Hofstra University. Bob Schieffer, Jim Lehrer, and Candy Crowley never asked about global warming during the 2012 debates. Nor did Martha Raddatz, who moderated that year’s vice presidential showdown.

As it turns out, though, the problem goes well beyond presidential debates. During the first 10 general election debates in competitive Senate and gubernatorial races this year, moderators asked no questions about global warming, according to research released last week by the liberal group Media Matters for America. Candidates occasionally brought up climate change on their own—that happened briefly in last week’s presidential debate—but the moderators simply ignored the issue. That meant zero questions about rising seas; zero questions about how devastating floods, heat waves, and wildfires are becoming more likely; and zero questions about the threat that the changing climate poses to our food supply and to our military operations and to international stability.

Finally, on Friday—the day after Media Matters published the initial installment of its debate scorecard—a moderator got around to asking about climate change. During a debate broadcast by WMUR (a Manchester ABC station), New Hampshire Sen. Kelly Ayotte (R) and her challenger, Gov. Maggie Hassan (D), were both asked whether global warming is real and what the government should do about it. Ayotte is somewhat unique among GOP politicians: She embraces climate science and even supports the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan—a set of regulations designed to cut greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector. The result was a pretty informative exchange. You can watch it below:

The Media Matters scorecard is an impressive undertaking—one that the researchers plan to update daily until the election. According to Andrew Seifter, the group’s climate and energy program director, the project involves constant news and database searches to track dozens of upcoming debates across the country, the videos and transcripts of which the researchers obtain and analyze. (Full disclosure: I used to work at Media Matters. Seifter is a friend and former colleague.)

In addition to showing what (if anything) was said about climate change at debates that have already taken place, the scorecard lists the broadcasters and moderators in charge of those that are coming up. The goal, says Seifter, is to empower concerned citizens to pressure moderators into addressing the issue. Rather than waiting until after the election season to release the results, he says, the scorecard will serve as a “living, research-based resource” that people can use to “demand change.”

The debates, Seifter argues, are the “best opportunity for the voters to learn about where the candidates stand” on climate change. So let’s hope more moderators start asking about it.