MauricioFC/Getty Images

This story was originally published by Project Earth/Fusion and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Climate change is a global problem with extremely local impacts. A major new study illuminates how the effects of climate change will reverberate economically across the United States. Its findings are both a warning of challenges to come and an opportunity to recalibrate how resources are allocated to protect Americans from global warming’s negative repercussions.

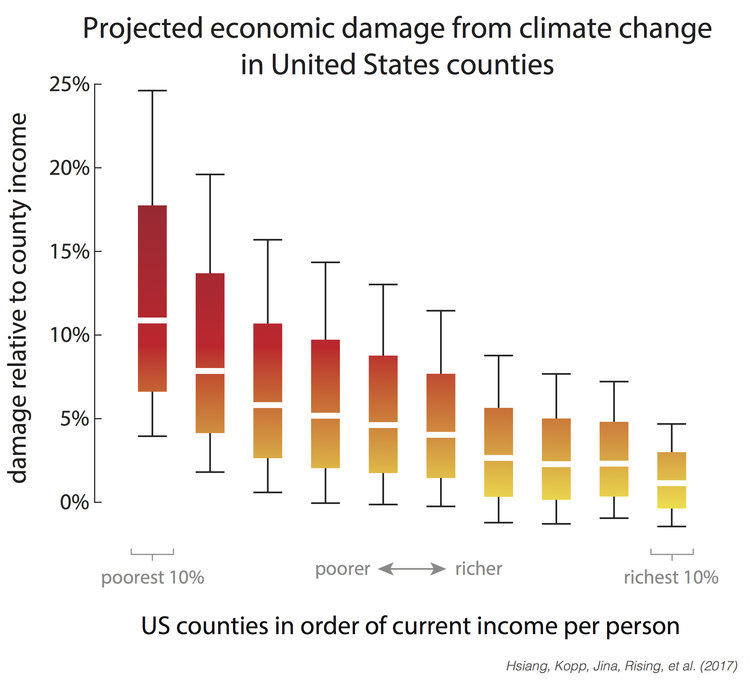

Published in the journal Science, the study found that unmitigated climate change will make the United States “poorer and more unequal,” with the poorest third of counties across the country potentially sustaining economic damages costing as much as 20% of their income. Furthermore, if emissions are not slowed and the planet warms 6-10°F (3-5°C) above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century, costs will approach those of the Great Recession—“except they will not go away afterwards and damages for poor regions will be many times larger.”

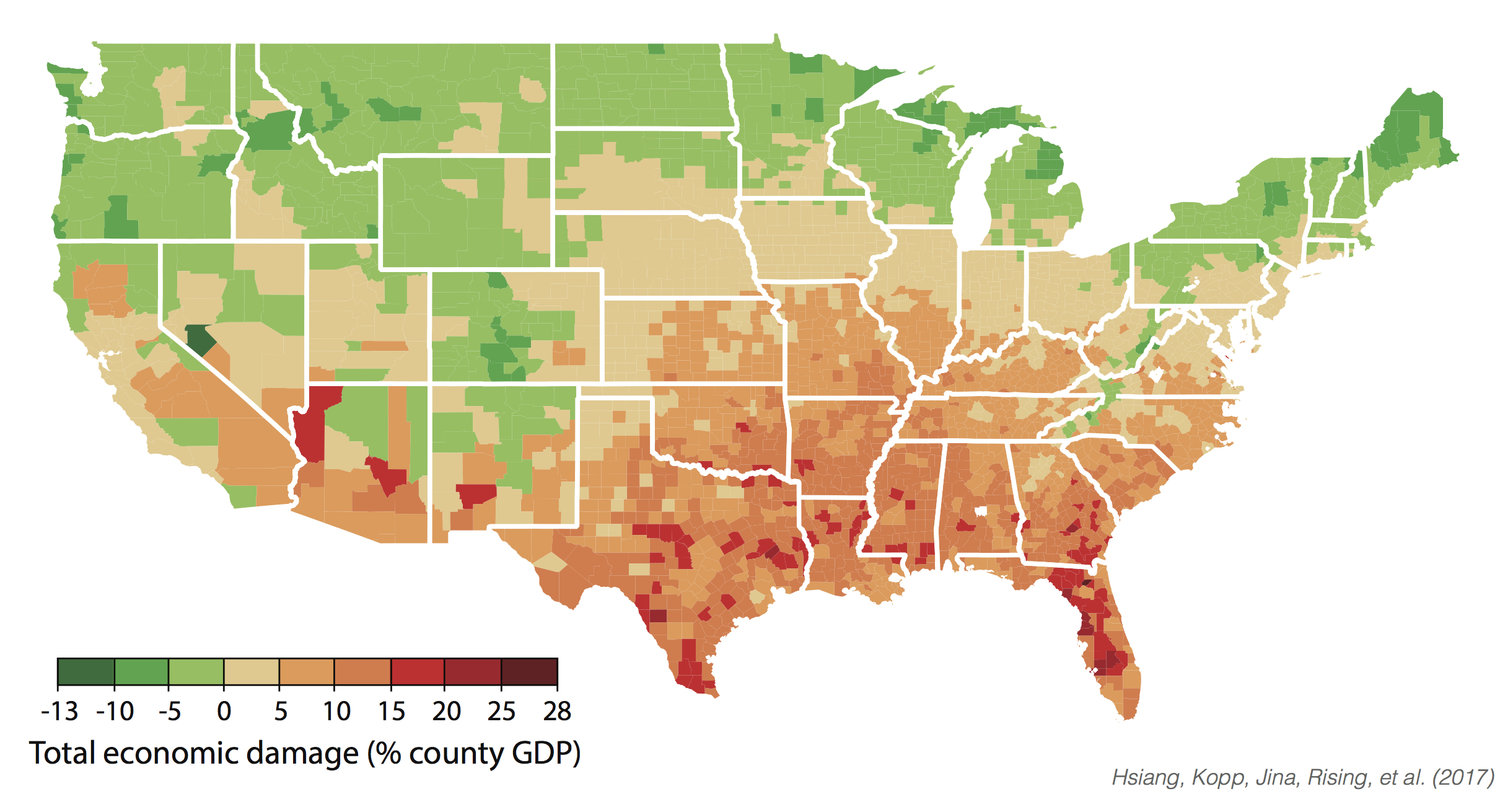

County-level annual damages in median scenario for climate during 2080-2099 under business-as-usual emissions trajectory (RCP8.5). Negative damages indicate economic benefits.

The team of economists and climate scientists looked at how six categories—agriculture, crime, health (mortality), energy demand, labor, and coastal communities—will be impacted by higher temperatures, changing rainfall, rising seas, and intensifying hurricanes.

Solomon Hsiang, the Chancellor’s Associate Professor of Public Policy at UC Berkeley and a co-leader of the study, said of the results: “If we continue on the current path, our analysis indicates it may result in the largest transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich in the country’s history.”

Amir Jina, a postdoctoral scholar in the department of economics at the University of Chicago and another co-leader of the study, told Project Earth he was very surprised by the extent of the damages being forecast.

Range of economic damages per year for groupings of US counties, based on their income (29,000 simulations for each of 3,143 counties). The poorest 10% of counties are the leftmost box plot. The richest 10% are the rightmost box plot. Damages are fraction of county income. White lines are median estimates, boxes show the inner 66% of possible outcomes, outer whiskers are inner 90% of possible outcomes.

People in the South stand to lose a lot more to climate change than those in the North in part because of temperature thresholds. The effects of temperature on different economic sectors are non-linear: the higher the temperature, the higher the damages.

“It doesn’t matter just how much you warm up, but also how close you are to the threshold where temperatures become really harmful,” said Jina. “This is the case in the South—it is already hot there, and it is going to heat up more, so people are getting pushed over those thresholds.”

Of the impacts studied, increased mortality will be the greatest direct economic cost from climate change, accounting for about two-thirds of the costs seen by the end of the century according to the study and using mortality values consistent with current U.S. government practices. Jina said this data could help inform how health care investments in infrastructure and other spending are distributed, as they will be needed more in some areas than others to offset the increased risks of climate change. For instance, the study found that warming reduces mortality in cold northern counties and elevates it in hot southern counties.

Jina hopes the study will help inform researchers and policymakers working to integrate the Social Cost of Carbon, a measurement of how rising CO2 emissions affect human welfare, into economic planning. He said he views the lack of such a cost right now to be a “huge distortion in the market” as even though we know CO2 emissions are causing damages, the cost of releasing them into the atmosphere is artificially set at zero.

Amir and others working in the intersection of climate change and the economy have started a group called the Climate Impact Lab. The team hopes to broaden the work of this study to a global scale and to calculate a social cost of carbon with as much real-world evidence as possible—perhaps for use by other government entities or future administrations.

D.J. Rasmussen, a co-author on the study and a PhD student at Princeton, told Project Earth that the detailed county-by-county analysis is in-depth enough to help decision makers at state and local levels estimate how climate change could impact their economies.

While the study paints one of the most detailed pictures of the winners and losers from the impacts of climate change in the U.S., Rasmussen cautioned that it’s far from complete, and that many other impacts still need to be studied.

“For example, in a warming world, we anticipate more unbearably humid days,” he said. “But we have yet to quantify the effect of humidity on, say, outdoor labor productivity. Anyone who has spent a summer in the mid-Atlantic or the Southeastern U.S. knows that it is not just the heat, it’s the humidity that makes you feel uncomfortable. Better quantifying the effects of humidity on the economy is on our to-do list.”