Angel Chevrestt/Zuma

This story was originally published by CityLab and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The fifth anniversary of Superstorm Sandy happens to fall just on the other side of a summer bookended by devastating storms.

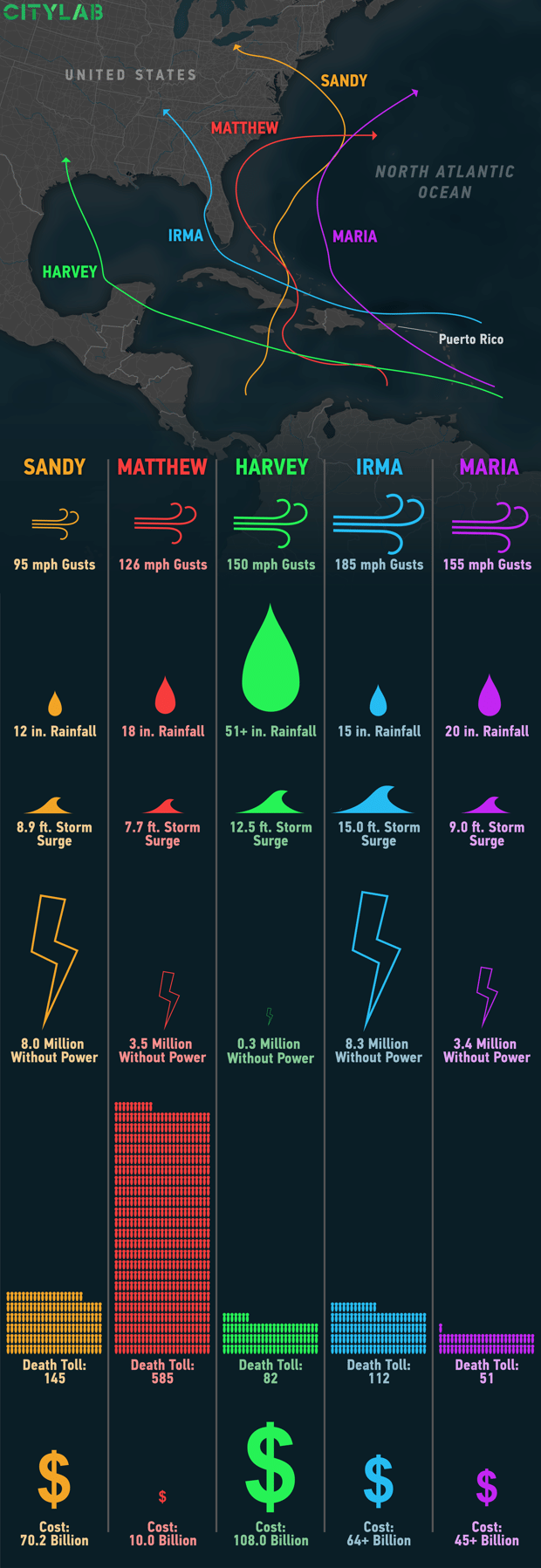

Below, we’ve collated damage reports to estimate how Sandy figures relative to the recent spate of disasters to strike U.S. shores, and to Hurricane Matthew, which knocked into solid ground this time last year.

Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Hurricane Center, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Weather Prediction Center, Department of Energy, National Weather Service, NASA.

Soren Walljasper/CityLab

A note about methodology: Whenever possible, we compared data collected by the same agencies over time. For all of the storms (Sandy, Matthew, Harvey, Irma, and Maria), we consulted bulletins and impact reports from the National Hurricane Center, a division of the National Weather Service at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In the case of the most recent storms, the latest NOAA data we consulted did not always include all of the variables. In those instances, we turned to other agencies within those parent institutions: We drew some rainfall, wind gust, and storm surge data for Harvey and Irma, for instance, from the Weather Prediction Center, which is nestled within NOAA. To pinpoint rainfall estimates for Maria, we used NASA data. To estimate power outages, we drew from event reports produced by the Department of Energy.

It’s worth noting that no single storm packed the strongest wallop on all fronts. While Sandy didn’t have the wildest gusts, the most rain, or the highest storm surge, the storm throttled infrastructure, grinding populous cities along the Eastern Seaboard to a halt. These numbers don’t tell the whole story. The comparatively modest power outages attributed to Harvey, for instance, belie the degree to which the storm disrupted the country’s existing energy infrastructure. (The week the storm lashed the Texas coast, petroleum inputs across the region plummeted 34 percent below the previous week, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.) Moreover, sheer numbers sometimes obscure the question of scope and scale: While the power outages caused by Hurricane Maria were fewer than those left behind by other storms, they represent vast devastation, with nearly every resident in Puerto Rico severed from the grid.

Superstorm Sandy

The storm caused deaths in the Caribbean, Haiti, and U.S. in October 2012, and devastated communities along the Eastern Seaboard. It vanished New Jersey beach towns, and sent water rushing into the New York subway system. Power outages extinguished electricity in 17 states. Five years later, repairs are ongoing in the hardest-hit areas. New York and New Jersey continue to shore up transit infrastructure ruined by seawater; repairs on some lines are not even forecast to begin until 2019. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration places the total cost of the storm at $70.2 billion.

Hurricane Matthew

Millions of residents lost power across Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia when the storm made landfall in October 2016, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. A buoy installed in the Chesapeake Bay by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers recorded a peak gust of 110 kh (126 mph). Gusts were even higher in the Bahamas (127 mph) and in Cuba (173 mph), where and rain exceeded 26 inches. The National Hurricane Center places the total damages at $10 billion.

Hurricane Harvey

A confluence of factors, including sprawl and development along the urban-wild interface, sharpened Harvey’s bite in August 2017. But the destruction was also due the fact that it held steady over Texas, instead of blowing through. As it hovered, the storm let loose more than 50 inches of rain in some parts of the state. Winds gusted above 130 mph in Port Aransas. The National Weather Service reported one storm surge cresting at 12.5 feet, as well as widespread flooding that drenched entire neighborhoods. A local meteorologist estimated that at one point, 70 percent of Harris County—which includes Houston and is one of the most populous in the entire country—was drowned in 1.5 feet of water.

Between August 27 and 28, there were 306,058 customers without power in Texas, and 8,215 in the dark in Louisiana, according to the federal Department of Energy. In total, that’s 2.5 percent of customers in Texas, and less than 1 percent of customers in Louisiana.

Estimates for Harvey’s total cost are in flux. (This is the case for other recent storms, too.) Though the true totals remain to be seen, they’re sure to be sizable, accounting for repairs, lost wages, and the storm’s disruption to the country’s energy sector. President Trump signed a bill allocating more than $15 billion in relief after Harvey and Irma.

Hurricane Irma

When the storm tore through the U.S. Virgin Islands in September 2017, it left catastrophic damage in its wake. General Deborah Howell of the U.S. National Guard told NPR that, in some places, towns had been leveled to rubble. “It almost looks like a bomb had exploded in the area,” Howell said, referring to damage in St. Thomas. Moving forward, Howell added, would entail rebuilding entire communities “from scratch.”

On September 8, the U.S. Virgin Islands Water and Power Authority reported that all of their customers on St. Thomas and St. John had lost power, since they were supplied by a single grid. That same day, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) reported that 870,403 people (more than 55 percent of their customer base) had been severed from the grid.

Irma pelted Florida with strong gusts of wind and, in Fort Pierce, more than 15 inches of rain. By September 11, 6,117,024 customers in Florida were without power. (This counts outages from Florida Power & Light plus other utility providers including Duke Energy Florida Inc. and Tampa Electric). The following day, millions of other customers across Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina saw outages.

Estimates of recovery costs vary widely, from about $45 billion to $200 billion. Many analysts revised initial estimates to reflect lower totals when the storm proved to be less destructive in Florida than experts had feared it would be.

Hurricane Maria

When the storm swept through Puerto Rico last month, it cut a wide swath of destruction, swamping roads and farms and stranding residents in hot, humid conditions with limited ways to cool off.

NASA measured widespread rainfall exceeding 20 inches. The power grid, which was fueled mostly by diesel, went offline, leaving nearly the entire island in the dark once again, soon after it had flickered back after Irma. Energy companies including Tesla and Sonnen have chimed in with offers to help transition the island to renewable sources, with a focus on solar—but PREPA, the bedraggled utility company that filed for bankruptcy in July, has already enlisted the Montana-based Whitefish Energy to rebuild the former grid. (Though these plans may come to a screeching halt: After many officials raised concern about the company’s small staff and modest-scale experience, Governor Ricardo Rosselló announced at a Sunday press conference that he had asked PREPA to rip up the contract.)

Last week, the Senate passed a bill that will funnel an additional $36.5 billion to recovery efforts. This bill, which is now awaiting President Trump’s signature, also earmarks $4.9 billion in low-interest loans for rebuilding efforts in Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Bloomberg reports that Puerto Rico’s governor, in addition to officials from recently drenched Texas and Florida, voiced concerns that the funding was insufficient. The full scope of damages, and the cost needed to repair them, has yet to come into clear view, but numerous estimates put the most conservative figure around $45 billion.

Meanwhile, the death toll will likely continue to rise. Since most of the island remains without cellular service and much infrastructure has been demolished, relief groups have been slow to reach regions far from urban centers. In the meantime, burials and cremations may not be added to the official tally—and the road to recovery will be long and steep.

Amanda Kolson Hurley, Teresa Mathew, and Alastair Boone contributed reporting.