Olivier Polet/Zuma

This story was originally published by CityLab and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Gotham Greens’ boxed lettuces have been popping up on the shelves of high-end grocers in New York and the Upper Midwest since 2009, and with names like “Windy City Crunch,” “Queens Crisp,” and “Blooming Brooklyn Iceberg,” it’s clear the company is selling a story as much as it is selling salad.

Grown in hydroponic greenhouses on the rooftops of buildings in New York and Chicago, the greens are shipped to nearby stores and restaurants within hours of being harvested. That means a fresher product, less spoilage, and lower transportation emissions than a similar rural operation might have—plus, for the customer, the warm feeling of participating in a local food web.

“As a company, we want to connect urban residents to their food, with produce grown a few short miles from where you are,” said Viraj Puri, Gotham Greens’ co-founder and CEO.

Gotham Greens’ appealing narrative and eight-figure annual revenues suggest a healthy future for urban agriculture. But while it makes intuitive sense that growing crops as close as possible to the people who will eat them is more environmentally friendly than shipping them across continents, evidence that urban agriculture is good for the environment has been harder to pin down.

A widely cited 2008 study by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University found that transportation from producer to store only accounts for 4 percent of food’s total greenhouse gas emissions, which calls into question the concern over “food miles.” Meanwhile, some forms of urban farming may be more energy-intensive than rural agriculture, especially indoor vertical farms that rely on artificial lighting and climate control.

An operation like Gotham Greens can recycle water through its hydroponic system, but outdoor farms such as the ones sprouting on vacant lots in Detroit usually require irrigation, a potential problem when many municipal water systems are struggling to keep up with demand. And many urban farms struggle financially; in a 2016 survey of urban farmers in the US, only one in three said they made a living from the farm.

Although cities and states have begun to loosen restrictions on urban agriculture, and even to encourage it with financial incentives, it has remained an open question whether growing food in cities is ultimately going to make them greener. Will the amount of food produced be worth the tradeoffs? A recent analysis of urban agriculture’s global potential, published in the journal Earth’s Future, has taken a big step toward an answer—and the news looks good for urban farming.

“Not only could urban agriculture account for several percent of global food production, but there are added co-benefits beyond that, and beyond the social impacts,” said Matei Georgescu, a professor of geographical sciences and urban planning at Arizona State University and a co-author of the study, along with other researchers at Arizona State, Google, China’s Tsinghua University, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Hawaii.

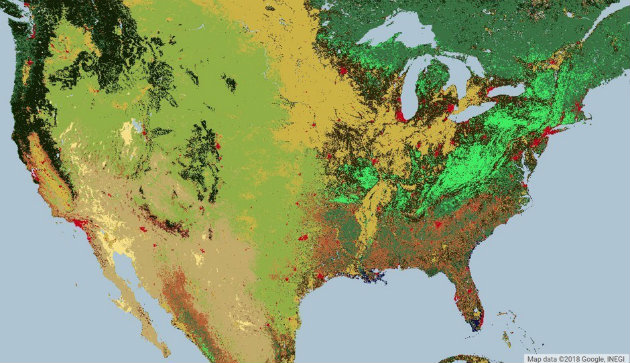

A MODIS Land Cover Type satellite image of the United States, similar to imagery analyzed by the researchers. Different colors indicate different land uses: red is urban; bright green is deciduous broadleaf forest.

Obtained from https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/ maintained by the NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center, USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science Center

Using Google’s Earth Engine software, as well as population, meteorological, and other datasets, the researchers determined that, if fully implemented in cities around the world, urban agriculture could produce as much as 180 million metric tons of food a year—perhaps 10 percent of the global output of legumes, roots and tubers, and vegetable crops.

Those numbers are big. Researchers hope they encourage other scientists, as well as urban planners and local leaders, to begin to take urban agriculture more seriously as a potential force for sustainability.

The study also looks at “ecosystem services” associated with urban agriculture, including reduction of the urban heat-island effect, avoided stormwater runoff, nitrogen fixation, pest control, and energy savings. Taken together, these additional benefits make urban agriculture worth as much as $160 billion annually around the globe. The concept of ecosystem services has been around for decades, but it is growing in popularity as a way to account, in economic terms, for the benefits that humans gain from healthy ecosystems. Georgescu and his collaborators decided to investigate the potential ecosystem services that could be provided through widespread adoption of urban agriculture, something that had not been attempted before.

The team began with satellite imagery, using pre-existing analyses to determine which pixels in the images were likely to represent vegetation and urban infrastructure. Looking at existing vegetation in cities (it can be difficult to determine, from satellite imagery, what’s a park and what’s a farm), as well as suitable roofs, vacant land, and potential locations for vertical farms, they created a system for analyzing the benefits of so-called “natural capital”—here, that means soil and plants—on a global and country-wide scale.

Beyond the benefits we already enjoy from having street trees and parks in our cities, the researchers estimated that fully-realized urban agriculture could provide as much as 15 billion kilowatt hours of annual energy savings worldwide—equivalent to nearly half the power generated by solar panels in the U.S. It could also sequester up to 170,000 tons of nitrogen and prevent as much as 57 billion cubic meters of stormwater runoff, a major source of pollution in rivers and streams.

Robert Costanza, a professor of public policy at Australian National University, cofounded the International Society for Ecological Economics and researches sustainable urbanism and the economic relationship between humans and our environment. He called the study (in which he played no part) “a major advance.”“We had no notion of what we would find until we developed the algorithm and the models and made the calculation,” Georgescu said. “And that work had never been done before. This is a benchmark study, and our hope with this work is that others now know what sort of data to look for.”

Costanza said he would like to see the researchers’ big data approach become standard in urban planning, as a way to determine the best balance between urban infrastructure and green space—whether it’s farms, forests, parks, or wetlands. That is the researchers’ hope as well, and they’ve released their code to allow other scientists and urban planners to run their own data, especially at the local level.

“Somebody, maybe in Romania, say, could just plug their values in and that will produce local estimates,” Georgescu said. “If they have a grand vision of developing or expanding some city with X amount of available land where urban agriculture can be grown, they can now quantify these added co-benefits.”

That could be very valuable, said Sabina Shaikh, director of the Program on the Global Environment at the University of Chicago, who researches the urban environment and the economics of environmental policy.“

Ecosystem services is something that is very site-specific,” she said. “But this research may help people make comparisons a little bit better, particularly policymakers who want to think through, ‘What’s the benefit of a park vs. food production?’ or some combination of things. It doesn’t necessarily mean, because it has the additional benefit of food production, that a farm is going to be more highly valued than a park. But it gives policymakers another tool, another thing to consider.”