Tom Williams/Congressional Quarterly/Newscom/ZUMA

This story was originally published by High Country News and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

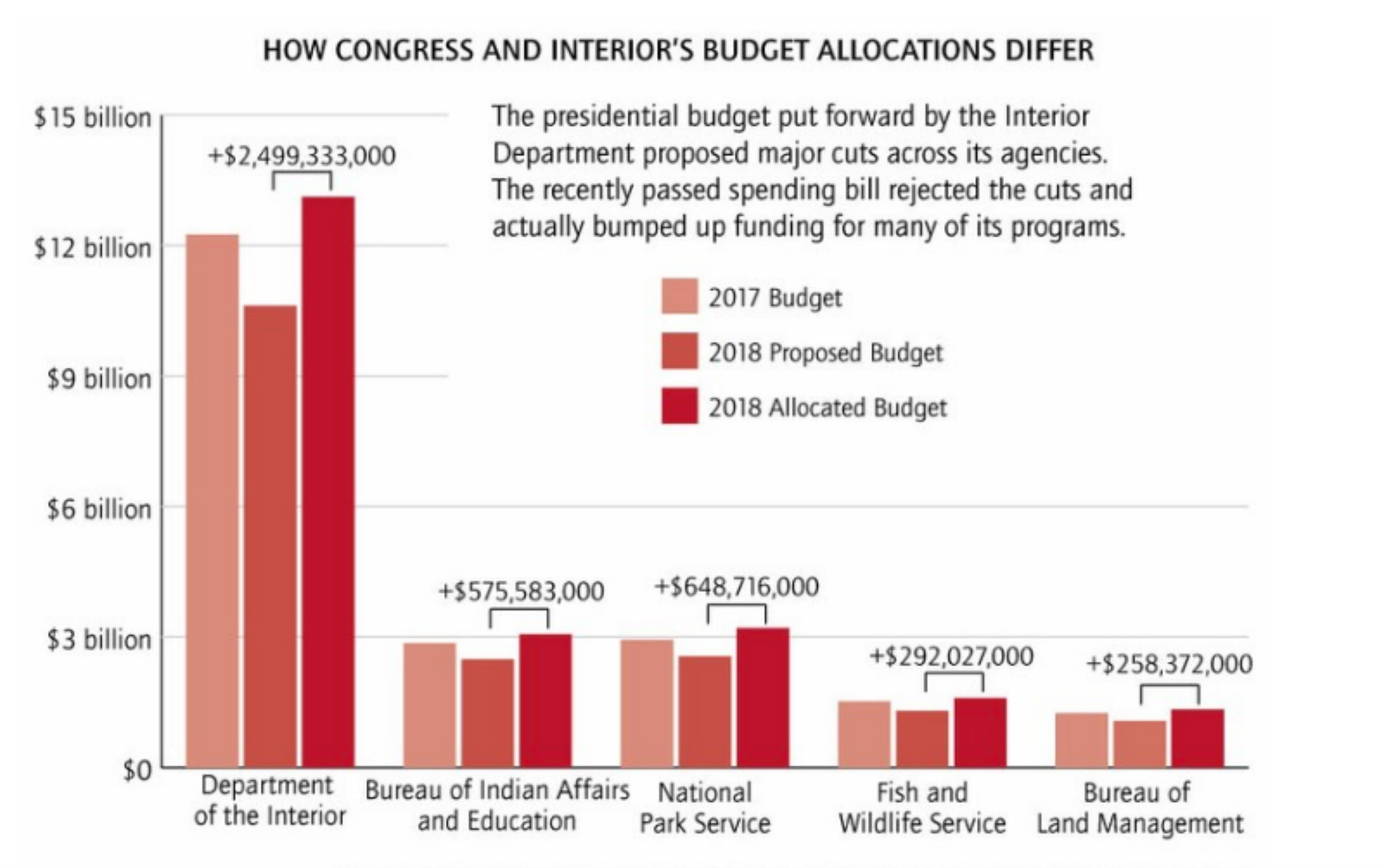

Since his confirmation in March 2017, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s push to trim the department he oversees while opening more public lands to energy development has been lauded by Republicans and denounced by Democrats. When it came to the budget, however, both sides agreed on one thing: no big cuts. In the omnibus federal budget, which recently passed with solid bipartisan support, Congress decided the Department of Interior was worth nearly $2.5 billion more than the administration had proposed.

The Trump administration had proposed substantial budget cuts at a time of record visitations to public lands, billions of dollars of maintenance backlogs, and some of the lowest staffing levels in decades at agencies like the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management. But in the appropriations bill signed March 23, the Fish and Wildlife Service and BLM each received more than a quarter billion dollars more than requested, and the National Park Service got almost $650 million more than the secretary asked for. Still, Zinke and the administration have other ways to cut back and redirect spending to bring it in line with their vision of budget cuts and bureaucratic reshuffling.

Among the programs that got a boost from Congress was the Land and Water Conservation Fund, which uses money from oil and gas leasing to support public lands access. The fund purchases land, provides grants to states and municipalities, and supports conservation easements for farmers and ranchers. Zinke’s department had proposed restructuring the program and cutting spending by over $330 million. Instead, Congress bumped up funding from $400 million in 2017 to $425 million in 2018.

Source: Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Appropriations Act, 2018

Brooke Warren/High Country News

The bill touted the importance of the Land and Water Conservation Fund for promoting recreational access and instructed the agencies to continue designating important lands that could be acquired through it. In a statement following the bill, the Nature Conservancy praised the program and the spending levels it set. “The passage of today’s spending bill demonstrates that bipartisan cooperation can lead to significant progress for conservation in America,” said Nature Conservancy CEO and President Mark Tercek in a press release.

Congress also increased spending on agencies that serve tribal nations. The administration’s proposed budget included more than $370 million in cuts to the Bureaus for Indian Affairs and Education and more than $100 million in cuts to BIA education programs. “These reductions are untenable and absolutely break the trust responsibility to Indian tribes,” the National Congress of American Indians stated in its analysis of the proposed budget.

Instead of going along with the proposed cuts, Congress voted to boost spending for the bureaus by more than $200 million over last year’s budget. Sen. Tom Udall (D-N.M.), who chairs the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, said after the bill’s passage that it “rejects the president’s dangerous proposed budget cuts and instead provides funding increases that will lead to healthier communities and better outcomes across Indian Country.”

Still, the administration is eyeing ways to work around the spending increases. Federal law prohibits agencies from not spending the allocated funds, but the executive branch can still ask for cuts and influence how money is spent through reviews of grants by political appointees and staffing shake-ups.

The relationship between the power of purse held by Congress and the executive’s authority to spend money can be traced to the Nixon administration. After Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972, President Richard Nixon decided that the price tag for the new legislation was too high. Nixon directed the Environmental Protection Agency not to allocate more than $10 billion in Clean Water Act grants between 1972 and 1974, much to the appropriators’ chagrin.

In response, Congress passed the Impoundment Control Act of 1974. The law created the Congressional Budget Office, a bipartisan office that advises Congress on budgeting matters, and led to the formulation of dedicated House and Senate appropriations committees that are responsible for crafting the federal budget. The law also required agencies to spend all the funds they’re allotted and established a formal process for the president to request reductions, called rescissions.

The Trump administration is currently working on a rescissions package with House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif). Matt Sparks, McCarthy’s communications director, confirmed that the representative is working on a package to trim the bill, but wouldn’t comment on possible cuts. If the administration asks for rescissions, Congress has 45 days to grant or deny its requests.

Since the Impoundment Act was put into place, the popularity of rescissions has ebbed and flowed. Presidential rescissions were popular during the Reagan administration, when Congress agreed to reduce spending levels by hundreds of millions of dollars. Recently, the tactic has fallen out of favor; neither George W. Bush nor Barack Obama made rescission requests.

The Trump administration seems to be examining all avenues in its pursuit of lower spending. Since the 2018 budget bill passed last month, President Donald Trump and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin have suggested that Congress should give the president the power to make line item vetoes, something that was ruled unconstitutional in 1998 after President Bill Clinton had been temporarily vested with the authority. Overturning the funding priorities set in the bipartisan spending bill would likely be a tough sell in the Senate, where Republicans hold a slim 51-49 majority.

Absent reductions to spending levels, Interior can stall funding for staffing and programs that don’t fit the vision of department leadership and redirect grants through a new process. Under Zinke’s leadership, the department has developed a political review process for grants doled out by its agencies, intended to make sure departmental grants match the administration’s political priorities. According to documents obtained by the Washington Post, many discretionary grants above $50,000 are subject to review by political appointees in Interior’s leadership. The memo specifically notes grants to nonprofit organizations and higher education institutions as being subject to review by Steve Howke, a lifelong friend of Zinke’s, who had a 30-plus-year career at credit unions before he joined Interior.

The agency can also plot its own course by moving around senior staff and pursuing buyouts, which can stall spending by creating vacancies in hard-to-fill positions. There are few ways to not spend money in congressional budgets, but “agencies can say they’re having a hard time finding people to fill jobs and drag feet on spending that way,” says Richard Kogan, a senior fellow with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a progressive economic policy think tank in Washington, DC. The department touts the moves as an effort to get more staff in field positions. But former Interior officials warn that losing senior staff could mean the loss of valuable experience, including knowledge of how the agencies work and of who their most important partners are.

Even as Interior comes to terms with the spending levels set by Congress, the budget hearings for the 2019 budget are already underway. And the second budget from the administration and Zinke looks similar to the first one, with major cuts to land management agencies and tribal programs. The response to Zinke’s trips to Capitol Hill to defend next year’s budget offers a clear indication of the partisan reaction to the administration’s vision for Interior. In a budget hearing before the Senate Energy and Natural Resource Committee, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Ala.) broadly praised the direction being set by Zinke and his willingness to open up new drilling sites in her state, while Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) called his tenure an unprecedented attack on public lands and an “abandonment of the secretary’s stewardship responsibility of our public resource.”

In this year’s budget, Congress rejected the slimmed-down version of the Interior Department proposed by Zinke and the Trump administration. With more time to evaluate the agency’s progress and direction, Congress will have the opportunity to set its own priorities for it again with the 2019 budget. How the department spends the 2018 budget will influence the amount and types of appropriations made for the next fiscal year. Moving forward, Congress can fund Zinke’s vision of a slimmer, reorganized Interior Department or, if lawmakers decide the administration is moving in the wrong direction, craft a more prescriptive budget that forces Interior to reflect the priorities of a Congress that has thus far rejected cuts to the department.

Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly identified New Mexico Sen. Tom Udall as chair of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. He is the vice chair.