Antarctica was once covered in forests instead of ice. Vincent van Zeijst

This story was originally published by Atlas Obscura and appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On their way back from the South Pole in 1912, Robert Falcon Scott and his team discovered the delicate lines of plant leaves pressed into the hard rock of Antarctica. They were “beautifully traced” fossils, Scott wrote. Despite the explorers’ fatigue and dwindling supplies, they collected samples, evidence that the icy expanse around them had once been far greener. When their bodies were discovered months later, so were the fossilized leaves of Glossopteris indica, a prehistoric tree that no longer exists, along with the preserved wood of a conifer.

The samples are some of the earliest bits of evidence that the frozen continent was once lush and covered in tall, thriving forests. They date back to the Permian period, more than 250 million years ago, when the planet was warmer than it is today. Though the land that would become Antarctica was part of the supercontinent Gondwana, it was still located at same extreme latitudes , where long stretches of light are followed by months of darkness. In those conditions a forest grew and, before it disappeared, left behind some of the best-preserved evidence of prehistoric plant life. By searching for the remains of Antarctica’s forests, scientists today are trying to discover what the world looked like all those years ago, just before one of Earth’s most dramatic extinctions wiped out most of the species living on the planet.

Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition at the South Pole. The explorers did not survive the return journey.

Because Glossopteris leaf fossils had also been found in South America, Africa, India, and Australia, they provided key evidence that the continents had once been connected as Gondwana—an idea that was a new theory at the time. Today, when researchers go fossil-hunting in Antarctica, Glossopteris leaves are among the most common finds.

“If you spend three or four hours at one site and you continually pull out materials, it’s usually the same type of plant,” says Rudolph Serbet, the collection manager in paleobotany at the University of Kansas. At most of the sites that Serbet and his colleagues visit, as part of a National Science Foundation research grant led by university professor Edith L. Taylor, they have just a few hours to sample and collect, during what will likely be their only visit to that particular site. “The chance of going back there ever again is pretty slim,” Serbet says. Only when they start to find something novel among the common—parts of plants that no one has ever seen before—do they return for more extensive work.

Sometimes the researchers find fields of prehistoric stumps, fossilized by minerals deposited inside, with their internal structures preserved. “One day, I climbed over this sandstone ridge, and there’s a big black tree stump,” says Erik Gulbranson, an assistant professor at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee who has participated in collection expeditions. “I look to my right, and there’s another tree stump, preserved as they would have stood.” Then he saw another stump, which looked to have been rotten at its center, and a few more.

The trees in these Antarctic forests grew as tall as 100 feet and their stumps can be three feet in diameter. Scientists now think that evergreens would have mixed with deciduous, and the ground would have been covered with a lower canopy of ferns and shrubby plants. In some ways, it would have looked like temperate forests the world over, but with a touch of the uncanny. “When you look around, you wouldn’t recognize any of the plants that were growing in this forest,” says Serbet. “Virtually all of these are extinct now.”

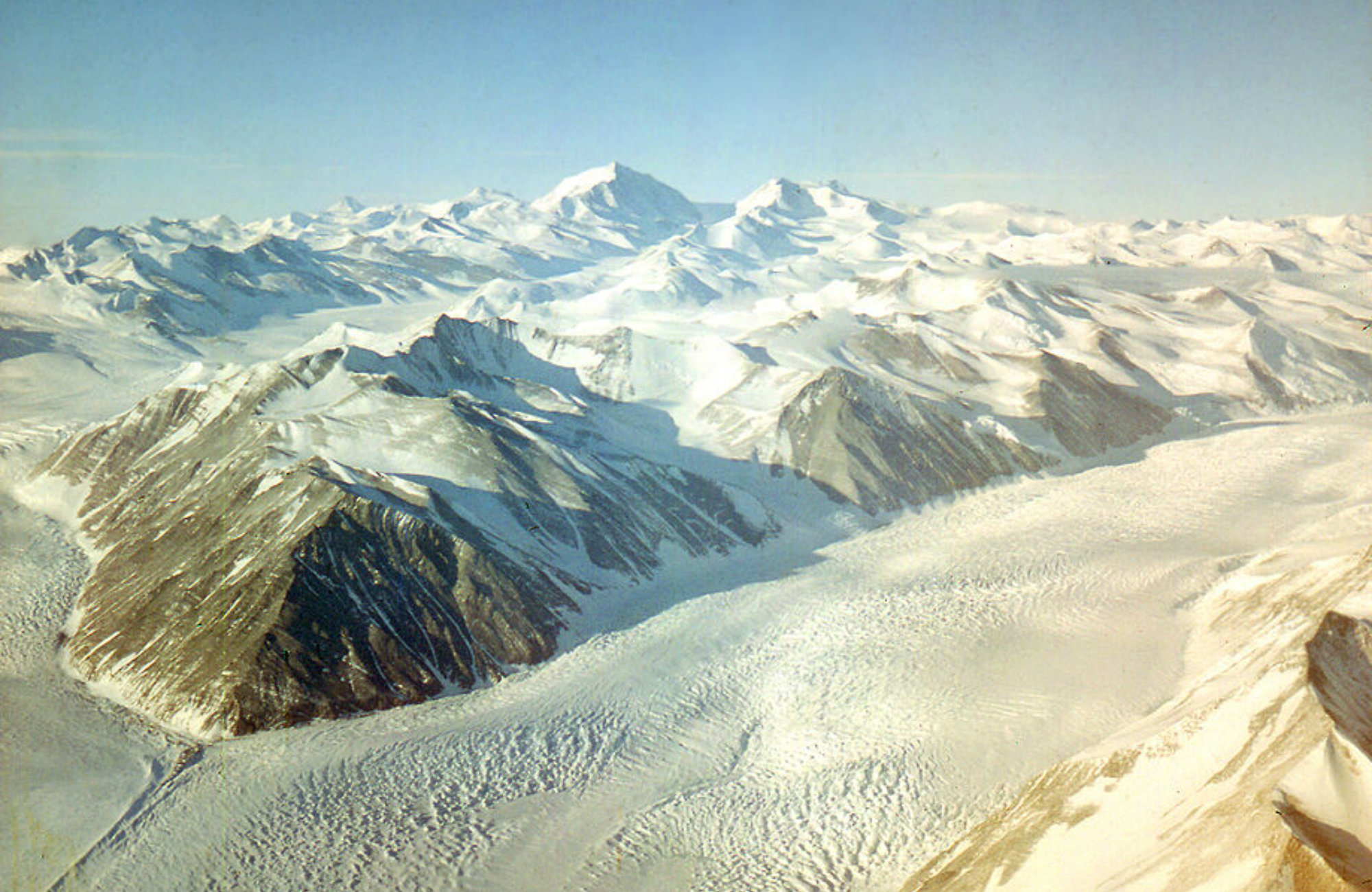

The Beardmore Glacier, one of the largest valley glaciers in the world, contains paleobotanical material.

The Permian is not the only period when Antarctica was covered in green. A mere 53 million years ago, that area of the world grew palm trees, and scientists have also discovered the mummified remains of mosses and other plants from just 14 million years ago. But the forgotten forest of 250 million years ago stands out, in part, because of the way it disappeared.

No one knows exactly what caused the mass extinction that ended the Permian, but it’s linked to a dramatic increase in carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere. The plants that lived in Antarctica had adapted to hard conditions—months in the dark, without the energy of the sun—but they were still vulnerable to change in the Earth’s climate. Understanding these ancient plants’ responses could help us understand how today’s plants will react to a replay of that atmospheric shift.

Even with the knowledge that the planet has been through major makeovers in the distant past, it takes a leap of imagination to picture the polar landscape—white, sere, inhospitable—as a forest. The image should feel like a shock. A forest at the South Pole would have a transformative effect on temperatures and weather across the globe, but imagine the condition of the rest of the world in which this is possible: different species, sea levels, rainfall, seasons—with or without us. We’re starting to see the polar march of plant species in both hemispheres even now, evidence that the forested past of Antarctica could be a window into its future.