A man beats the heat at the Logan Square fountain in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto via ZUMA Press

This story was originally published by the Guardian. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

On yet another day of roasting heat in Phoenix, elderly and homeless people scurry between shards of shade in search of respite at the Marcos De Niza Senior Center. Along with several dozen other institutions in the city, it has been set up as a cooling center: a free public refuge, with air conditioning, chilled bottled water, boardgames and books. Last summer a record 155 people died in Phoenix from excess heat, and the city is straining to avoid a repeat.

James Sanders, an 83-year-old who goes by King, has lived in the city for 60 years and considers himself acclimatized to the baking south Arizona sun. “It does seem hotter than it used to be, though,” he says as he picks at his lunch, the temperature having climbed to 107 degrees Fahrenheit outside. “Maybe it’s my age. Maybe the wind isn’t blowing. It can’t get much hotter than this though. Can it?”

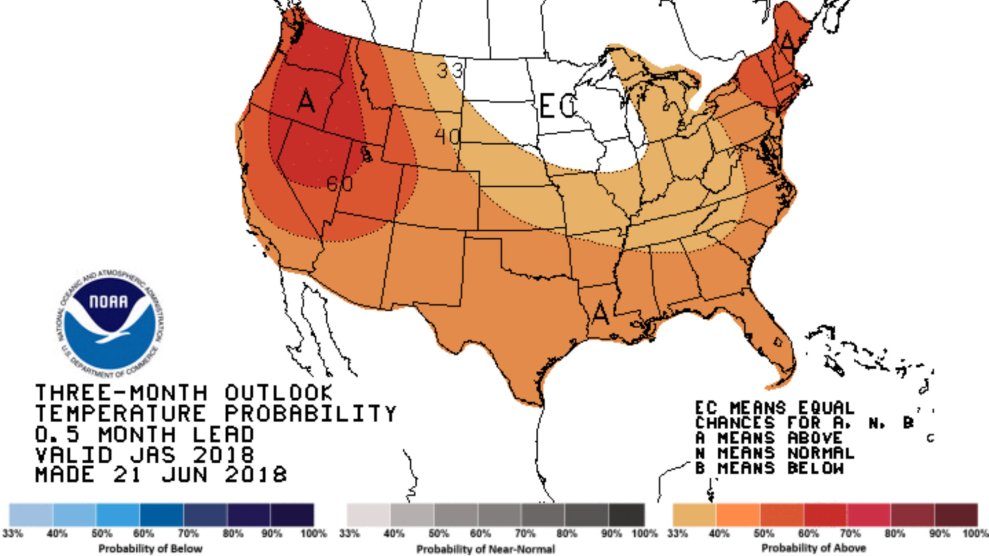

The heat wave that has recently swept the US has put 100 million Americans under heat warnings; caused power cuts in California where temperatures in places such as Palm Springs approached 122 degrees; and resulted in deaths from New York to the Mexican border, where people smugglers abandoned their clients in the desert. Further north, in Canada, more than 70 people perished in the Montreal area after a record burst of heat.

Record temperatures raise wrenching questions about the future viability of cities such as Phoenix, where taking a midday jog or doing a spot of gardening can pose a deadly risk. Climate change is spurring increasingly punishing heat waves that are projected to cause tens of thousands of deaths in major US cities in the coming decades.

“There’s a point where the human body can’t cool itself, which means you are either in an air-conditioned space or you’re having serious health problems,” says Gregory Wellenius, an epidemiologist at Brown University. “Some places in the US will get to that point. The way we live, work and play will be altered by rising temperatures.”

Heat already kills more Americans than floods, hurricanes or other ecological disasters. That puts sweltering cities like Phoenix – where flights were cancelled last year because it was simply too hot— under growing pressure. But heat is rapidly becoming a national problem.

Recent research suggests warming conditions are leading to suicides, as rising nighttime temperatures deprive Americans of sleep and respite from scorching days. A new study, released last week, predicts that a warming climate will drive thousands to emergency rooms for heat illness. The very hottest days experienced in the US could be a further 15 degrees warmer this century if greenhouse gas emissions aren’t curbed.

A national plan to deal with heat, however, remains a distant prospect, as the Trump administration attempts to demolish almost every measure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. It has also outlined deep cuts to climate programmes, and steered federal agencies away from adapting to more frequent and more extreme weather events such as heat waves, flooding and stronger storms. For the most part, US cities are facing burgeoning heat waves on their own.

The Center for Disease Control states that around 650 deaths occur a year due to heat but Wellenius argues that this is too conservative, as heat isn’t always explicitly cited on death certificates; with related mortality the total swells to around 3,500. Crucially, the death toll is afflicting US cities that haven’t previously had to spend much time fretting about heat.

Research published by Wellenius and colleagues last year found the burden of these deaths is shouldered by unlikely places, far from the parched cacti and canyons of the west. The relatively cooler eastern cities of Philadelphia and Baltimore jointly have the most excess deaths due to heat in the entire US, at 37 fatalities per million people each year, the research found. July temperatures in Baltimore and Philadelphia have a long-term average of around 77 degrees; in Phoenix it’s 93 degrees. In all three cities, as elsewhere on the planet, the average is climbing.

Beyond setting up the cooling centers, mainly in libraries, so far the response in Philadelphia has focused on raising public awareness, with city officials bombarding residents with advice in English and Spanish to “Stay Cool Philly!”, avoid the sun, drink water, and check on elderly neighbors.

“I think some of the other things people are in the west may be a little more attuned to the issues – like don’t jog your five miles at noon, do it at 5 a.m.,” says Dr. Caroline Johnson, a senior official at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. “Some of that may come as a surprise to people around here.”

Improvements in treating heat exhaustion and heat stroke mean that spikes in hospitalizations— around 40 people were taken to hospital in Philadelphia for heat in the first week of July—don’t necessarily lead to a surge in deaths. But older cities in the US northeast, like Philadelphia, were built at a time when rapid change into a new climate was virtually unimaginable.

Much of Philadelphia’s older housing is packed tightly together in terraces, with little air circulation and no air conditioning. Roofs are still slathered in tar, rather than more expensive reflective materials, trapping more heat. “They’re like little ovens in there,” says Johnson.

Clusters of these houses, largely found in poorer, minority areas in the north and east of the city, can be as much as 8 degrees hotter than the Philadelphia average, according to city officials. Leafier, wealthier suburbs can be as much as 14 degrees cooler than the average. Being poor often means hotter homes, waiting in the sun at bus stops rather than sitting in air-conditioned Ubers, and being unable to escape to cooler climes on vacation.

“When it gets real hot I try to keep an eye on the older residents,” says Joann Taylor, who has lived in the largely black and Latino district of Hunting Park for 47 years. “They don’t have air conditioning, so I just tell them to keep the blinds closed. The houses could do with some updates to cope with the heat.”

Philadelphia has embarked upon a mission to slash its greenhouse gas emissions, plant hundreds of thousands of new trees, and upgrade its parks in order to provide a haven from the warmth. But the specter of a particularly deadly summer—perhaps a repeat of July 1993 when 118 people died in Philadelphia due to heat—feels ominously close. Without a severe drop in emissions, Philadelphia will spend around 100 days a year above 90 degrees within 30 years, double the number of hot days experienced in 2000.

“I think what scares me is that the projections are that things are only going to get worse,” says Christine Knapp, director of Philadelphia’s office of sustainability, sitting in her mercifully cool office as the city endured the latest in a string of days over 86 degrees.

“This heat wave is very emblematic of what we will likely continue to have. My aunt lives in Arizona where it’s hot all the time. They set up [Phoenix] knowing that was a desert; you go from your air-conditioned car between air-conditioned spaces. They are hotter but they’re better prepared than we are.”

But while Phoenix’s buildings are newer and largely air conditioned, any power outage can cause an emergency situation. And familiarity with the burning sun doesn’t provide any protection from it—of the 155 people who died in the Phoenix area last summer, all but three were from Arizona.

“We encounter this feeling from the populace that perhaps once you’ve acclimated to the weather here or you’ve lived here for a certain amount of time, you’re no longer really as vulnerable to the heat,” says Kate Goodin, an epidemiologist at the health department of Maricopa County, in which Phoenix sits. “Obviously, that’s not true socially or biologically.”

Phoenix is looking to create long corridors of shade-providing trees to allow people to venture out of their homes and cars during the day.

But the future warmth will be brutal and lengthy. Maricopa County will spend two-thirds of the typical year in heat of more than 100 degrees by the time today’s preschoolers are drawing a pension. Further adaption will be possible, but the ability to carve out a comfortable life in the desert is being gradually dismantled.

Those wealthy enough to move have an escape route. Disadvantaged communities face starker realities. “There’s some system changes that we need to be making so that people can live within this community if they so choose,” Goodin says.

Though the federal government is currently trying to extricate itself from the scientific reality of climate change, at some point it will have to deal with the societal implications of huge swathes of the country requiring expensive modifications to support a human populace.

“It’s only a matter of time until the west is completely insufficiently prepared for climate change,” says Brian Petersen, a climate change and planning academic at Northern Arizona University. “If we really wanted to be prepared we would be doing a lot of different things that we’re not doing.

“The fact is, there’s not going to be enough refuge for everybody.”