Joe Raedle, Getty Images

No city better embodies the challenges of climate change than the setting for the first Democratic debate in June. At least 10 candidates who meet the Democratic National Committee’s set of polling and grassroots fundraising criteria will take the stage in Miami, a city that will face the threat of encroaching seas on a daily basis over the next 25 years. Many of the climate activists who have urged presidential hopefuls to embrace the Green New Deal and reject donations from fossil fuel industries are preparing for their next battle: pushing for a presidential debate focused entirely on climate.

Environmental and progressive groups, including 350.org, Greenpeace, Sunrise Movement, Credo Action, and Friends of the Earth, plan to ramp up campaigns calling on the DNC, as well as the major TV networks and 2020 candidates, to dedicate one of the dozen official debates to a subject that has never gotten its due in primetime.

“We’re seeing a shift in people’s consciousness,” Janet Redman, Greenpeace’s climate program manager, told Mother Jones. “We need to see that starting to be reflected in our politics—that it’s not an isolated set of incidents or phenomenon. The public is craving politicians to have a conversation on this. They want to know real solutions.”

It’s not the first time activists have tried to persuade the DNC to give climate change some attention in the debates. The DNC doesn’t control the questions that are asked—that’s up to the networks that wind up partnering with the DNC for the events—but there have been debates focused on broad themes like national security and the economy. Through a combination of bird-dogging, protests, online campaigns, and the rising profile of climate change in the national conversation—plus growing evidence of its severity and grave consequences—activists have become more ambitious, seeking a full 90 minutes focused on the finer points of climate action.

The hyperpartisan nature of the climate debate tends to obscure the fact that there is a huge spectrum of proposed solutions for addressing the problem. “It’s like saying we shouldn’t have a debate on health care because all Democratic candidates agree more people should have access to health care,” says Evan Weber, political director of Sunrise Movement. In the past, when candidates are asked about this at all, the questions tend to be about whether a candidate believes in climate change, thinks of it as a priority, or has any plan for action.

Even now, it’s easy to imagine how candidates will express their commitment to a Green New Deal and deflect specifics with some applause line about climate change as an existential threat, a national security threat, or an opportunity to show American leadership. Moderately talented politicians could avoid addressing the challenges and paths forward on climate. For instance, beneath the generally universal enthusiasm for the Green New Deal, there are huge fractures about whether the traditional gold standard of a carbon tax championed by economists should be included, or how to handle nuclear power, or how to handle fracking and the continued leasing of lands for fossil fuels.

“My fear is there will be some softball climate questions that aren’t specific, aren’t digging deep, [and] therefore make it hard for us to make any candidate who is elected accountable,” Redman says. “What we’re trying to do by focusing on primaries is pulling the entire field of candidates to bolder positions.”

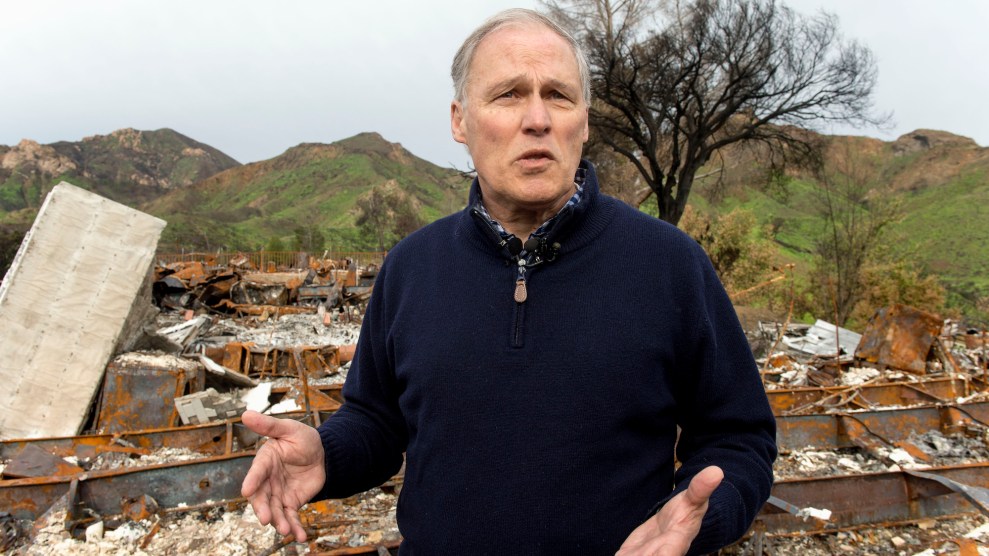

One of those bolder positions would be to force candidates to take a clear stand on where fossil fuel leasing and production fits into their climate plans. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have taken definitive positions saying they would reject new leasing on public lands, but Beto O’Rourke, Joe Biden, and Kamala Harris have not shared their opinions on the future of natural gas, despite voicing their support for the Green New Deal. Another question would be how climate fits into the candidates’ priorities. Should Washington Gov. Jay Inslee make the stage, he is likely to ask other candidates to demonstrate that it’s a priority by promising specific action during their first 100 days in office.

Climate has always faced an unnaturally high bar to make it to the debate stage, long considered a niche issue rather than a central concern, despite tens of thousands of Americans losing their homes to fires, mudslides, and floods. That was clear in 2012 when Mitt Romney and Barack Obama appeared at the CNN debate and its moderator replaced a question “for all you climate change people” with one about the national debt. There were no direct questions on solving the climate crisis that cycle, nor were there questions in the general election debates in 2016. (The Democratic primary featured some debate centered around fracking.)

But this election cycle is likely to be different. After another year of record wildfires and extreme weather, capped off by alarming headlines from the normally staid Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Democratic primary voters have never been more concerned about climate. According to a Des Moines Register, CNN, and Mediacom poll in March, 80 percent of those polled said candidates should spend “a lot” of time talking about climate change, placing this issue only second to concerns about health care. And the vision for the Green New Deal, when stripped of partisan context, has polled at astoundingly high rates across partisan lines.

The DNC has no plans yet for any issue-specific debates, other than providing a “platform for candidates to have a vigorous discussion on ideas and solutions on the issues that voters care about, including the economy, climate change, and health care,” DNC spokeswoman Xochitl Hinojosa told Mother Jones by email. Unlike Republicans stuck in climate denial, “Democrats are eager to put forward their solutions to combat climate change, and we will absolutely have these discussions during the 2020 primary process.”

Greenpeace’s Redman says this promise “absolutely falls short.”

“I think it’s night and day,” says Brandy Doyle, climate campaign manager for the progressive advocacy organization Credo Action. Grassroots activists and climate campaigners “worked really hard to inject the idea of climate change in the conversation in 2016, to even push for a question on climate change in the debates.”

For activists, the key to forcing these debates is to apply public pressure to hold the eventual nominee accountable, which becomes seemingly impossible in a general election focused on drawing a contrast to Trump. “If you can’t articulate the urgency of the climate crisis and your vision for addressing it,” Doyle says, “you’re not qualified for president.”