A farmer climbs out of a salt-caked dry irrigation canal on a farm near Stockton, Calif, in 2015, during California's worst drought in recorded history. Rich Pedroncelli/AP

The Trump administration’s department of agriculture has apparently settled on its strategy for preparing the food system for an uncertain future: ignore climate change.

This wasn’t always the agency’s tactic. Back in 2017, as Politico’s Helena Bottemiller Evich recently reported, the USDA was set to release a big plan on how to “help the agriculture industry understand and adapt to climate change.” But “top officials chose not to release the report, and told staff it should be kept for internal use only,” Bottemiller Evich wrote. Weeks before, Bottemiller Evich reported about how the USDA’s top decision makers have systematically “refused to publicize” its own scientists’ research on the impact of climate change on farming.

In the meantime, farmers have already started to feel that impact. A disastrously wet spring in the Midwestern farm belt—consistent with the types of storms that are expected to become more prevalent—delayed planting by weeks and led to the loss of millions of tons of soil. As a result, a huge swath of the US corn and soybean crops are in “poor or very poor condition,” American Farm Bureau Federation economist John Newton told the trade journal Brownfield last week. He says the 2019 harvest is shaping up the be the worst since 2012. That year, a historic drought, combined with hotter-than-normal temperatures, slashed yields in key corn growing states like Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Missouri.

A 2018 report called the Fourth National Climate Assessment confirms that climate change is already having a dramatic impact on farms, and is only getting started. The National Climate Assessment is a collaboration among 13 federal agencies that was mandated by Congress back in 1990 and is obliged to deliver reports every four years, so the the Trump administration could not squash the release outright. Instead, it made a brave effort to to bury the assessment, literally releasing it without fanfare on the Friday after Thanksgiving.

The report, along with one released around the same time by the state of California, outlines the massive challenges faced by farms as the climate warms. Here are three major issues that are worthy of hair-on-fire attention by USDA researchers.

• Fruit and vegetable farms get parched. California farms are American’s main source for a roster of the foods we’re always being urged to eat more of: Altogether, they churn out more than a third of vegetables and two-thirds of both fruits and nuts grown in the country.

The state’s $50 billion agricultural behemoth would be impossible without billions of dollars worth of infrastructure conveying melted snow from mountain ranges to California’s hot, dry Central Valley and the even hotter, drier Imperial Valley.

Snowmelt sources for both regions are already under pressure from climate change, and the trend line points downward. The Central Valley relies on irrigation water from the Sierra Nevada; but “as a result of projected warming, Sierra Nevada snowpacks will very likely be eradicated below about 6,000 feet elevation and will be much reduced by more than 60 percent across nearly all of the range,” the California Climate Assessment warns. Imperial Valley farmers draw their water from the Colorado River, which carries snowmelt from the Rocky Mountains. Hotter temperatures both reduce the snowpack and cause more water to evaporate on the long journey from the northern Rockies to southern California. The report warns that Colorado River flows will drop by as much as 30 percent by mid-century and 55 percent by the end of the century.

As the Colorado dwindles, Imperial Valley farmers will also face severe political pressure to cede more of their allotted water to booming metropolises like San Diego, the report adds. In short, California-made desert valleys blossom into our national fruit and vegetable garden during times of plentiful snowmelt, but that era is on its way out.

• The corn belt gets deluged. The Midwest’s brutal spring may have been less an anomaly than the shape of things to come, the Fourth National Climate Assessment suggests. And that’s bad news for farmers in the region that supplies the food system with the corn and soybeans that drive meat production and provide cheap sweetener and fats for processed food.

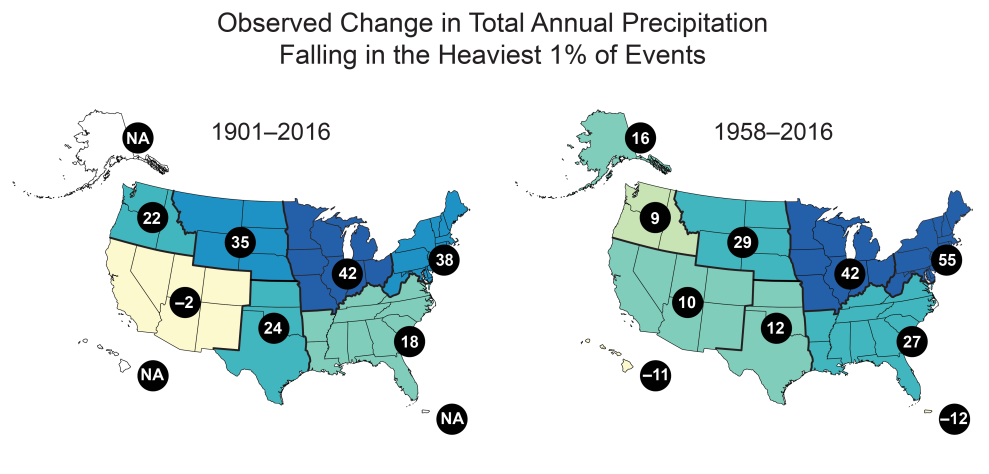

The report found that the Midwest’s precipitation patterns have already shifted dramatically. More and more rain and snow comes in the very kind of brief, violent spasms that caused so much trouble in 2019. To measure increasing storm intensity, the researchers looked at changes in the portion of annual precipitation that falls in the top one percent most-intense storms over the course of each year since 1901 and 1958. Here’s what they found in each region:

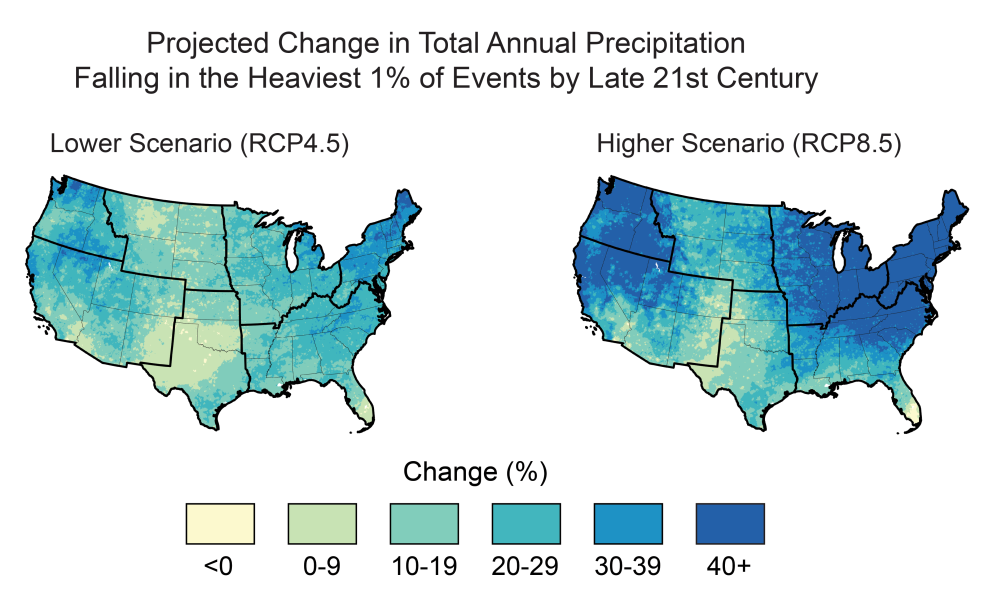

Note that for the Midwest, the entire 42 percent jump in storm severity took place after 1958—suggesting that today’s farmers are encountering a weather regime radically different from that of their grandparents. The Climate Assessment researchers also looked at what warming trends portend for the next several decades, using an optimistic scenario for cuts to global greenhouse gas emissions going forward as well as a business-as-usual outlook. Both point to a continued rise in storm severity, and thus ever-heavier pressure on the Corn Belt’s soil.

As for farming, “increases in humidity in spring through mid-century are expected to increase rainfall, which will increase the potential for soil erosion and further reduce planting-season workdays due to waterlogged soil,” the report found.

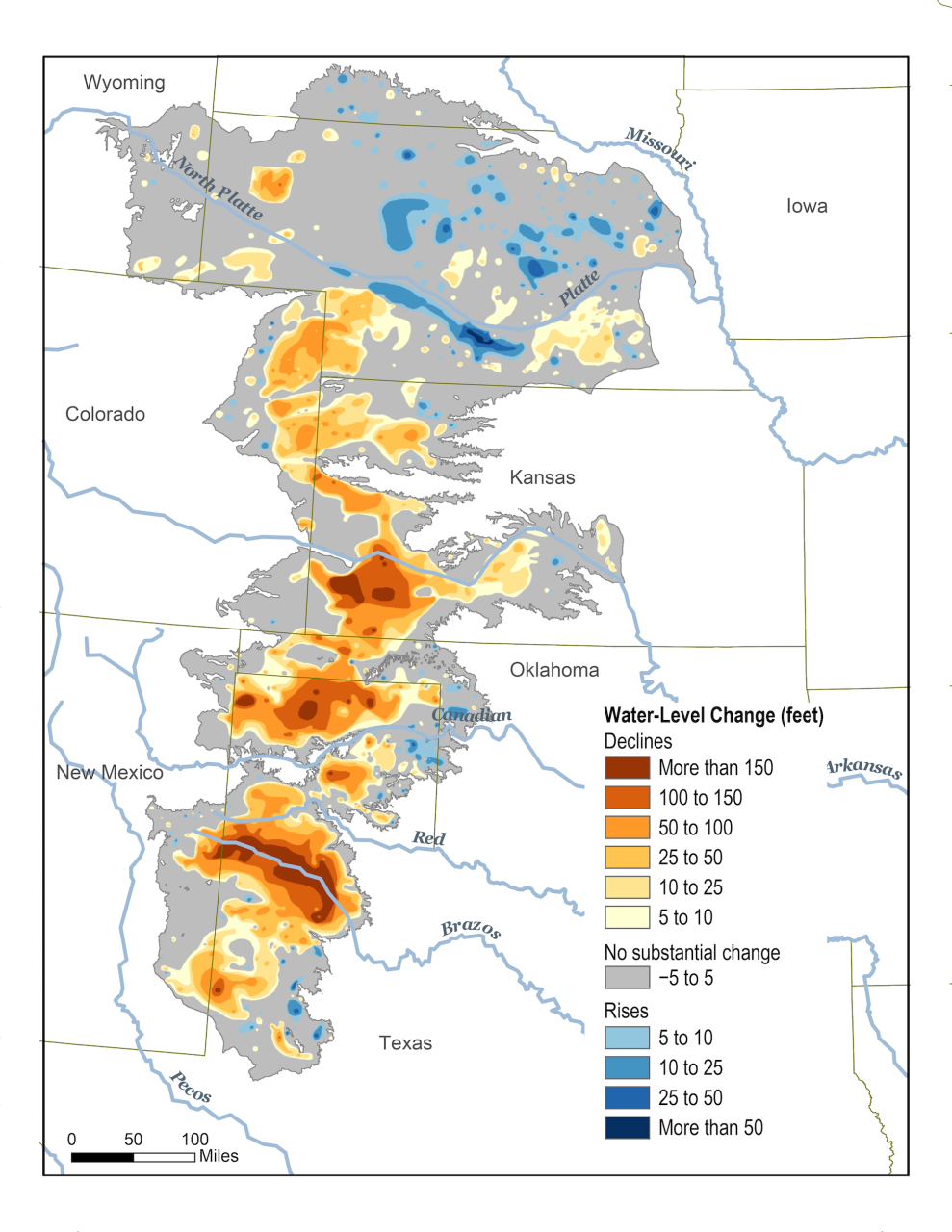

• The breadbasket withers. While the Midwest struggles with an overabundance of rain, especially in the spring, the much more arid Great Plains region just to the west has the opposite problem. A large swath of the area, from the Kansas-Colorado border to the Texas panhandle, sits atop the Ogallala Aquifer, a kind of vast underground lake that supplies irrigation for the “most productive farm belts in the world,” the climate assessment reports. The region’s farms produce $35 billion worth of goods annually, including “one-fifth of the Nation’s wheat, corn, and cotton, and the southern half of the region accounts for more than one-third of the beef cattle production.”

Now the bad news: “current extraction for irrigation far exceeds recharge in this aquifer,” and farmers in many areas are already seeing “reduced well outputs due to excessive pumping,” which has triggered “recent dust storms that were similar to those of the 1930s and 1950s.”

As the graphic above shows, large swaths of the Ogallala have seen water depths drop by at least 50 feet since settlers first established irrigated agriculture in the region. A projected increase in summer droughts will ramp up pressure on this already-shriveling jewel of agriculture, the report adds.

In short, farmers in these key regions are grappling with the challenge of producing enough food while preserving soil and water resources in an era of climate chaos. It would be nice if the department of agriculture would acknowledge the difficulty of task, and call on its research apparatus to hunt for—and publicize—solutions.