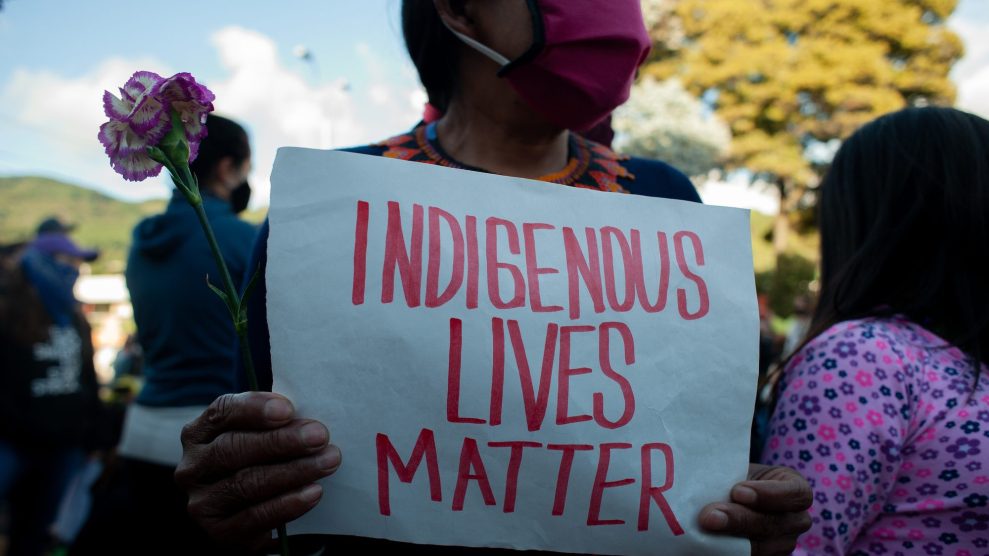

An indigenous woman demonstrating.Sebastian Barros/Getty

This piece was originally published in High Country News and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

As US government scientists work to understand how COVID-19 affects the human body, tribal nations are still struggling with the impacts of the federal government’s inadequate response to the pandemic. Now, through a National Institutes of Health program called “All of Us,” tribal nations across Indian Country are pushing federal scientists to conduct disease research that serves Indigenous peoples in a meaningful way. Developing research practices in accordance with tribal consultation takes time, however, meaning that for now, tribal citizens are missing out on the program’s coronavirus antibody testing.

The All of Us study aims to collect, sequence and catalog DNA representative of the United States’ diverse communities. This vast project will enable research such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes and autoimmune diseases from across the country. But tribal nations are concerned about the ownership and control of this data, which can affect a number of things: patents and intellectual property rights, the privacy of tribes, future research and even access to basic information and health care.

“We’re concerned about access to data as well as release of data without tribal permission,” said Dr. Stephanie Russo (Ahtna-Native Village of Kluti-Kaah), University of Arizona public health professor. “What the pandemic has shed a light on is the need for tribes to have access to external data.”

The coronavirus pandemic has given the Indigenous data sovereignty movement a new sense of urgency. As pharmaceutical companies, researchers and governments scramble to create COVID-19 tests and vaccines, many tribal leaders and Indigenous data and public health experts are wary of participating in research that may have little benefit for their communities.

The Indigenous data sovereignty movement emerged in 2015, when Indigenous researchers convened in Australia to discuss research on Native peoples and Indigenous rights under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. They concluded that Indigenous nations retain ownership over their citizens’ data, as well as the power to decide how that data is used. All this made news earlier this year, when the US was widely criticized for a major data breach that leaked the financial data of tribal nations that had submitted applications for COVID-19 relief.

What’s more, in the past, medical researchers have stigmatized and harmed Indigenous communities. In some cases, they did not report their findings to the tribes who participated. A 1979 study on an Inupiat community in Alaska resulted in widespread publicity on the community’s alcohol use, encouraging harmful stereotypes. Researchers who took blood samples from the Havasupai Tribe in 1989 conducted a diabetes study and allowed other researchers to access the samples without the tribe’s knowledge or consent. The federal government’s past use of ancestry, such as blood quantum, to terminate tribal nations and limit tribal sovereignty, means there is little trust today for government-funded genetic research. This is why tribes insist on sharing ownership of the data collected by All of Us. It would empower them to have input regarding future research that makes use of Indigenous data.

“Understand: Data is a resource,” said Keolu Fox (Kanaka ‘Ōiwi), assistant professor of anthropology at University of California-San Diego who studies genome science and Indigenous communities. Fox has argued that unrestricted access to genome data by state governments and pharmaceutical companies is a threat to tribal sovereignty and may have little direct benefit aside from individual test results—meaning tribes will likely not receive subsidized medications, intellectual property rights or royalties in return for their data. During a May National Institutes of Health tribal consultation, NIH researchers recognized the minimal benefits of Indigenous participation, as Fox noted, stating that the primary gain would be those individual test results.

After tribes and Indigenous experts began voicing their concerns about All of Us over a year ago, NIH prohibited researchers from collecting data on tribal lands. It has also halted release of data results from participants who identify as American Indian or Alaskan Native. The researchers also agreed not to publish tribal affiliations of participants without the consent of the tribal nations. This means that All of Us is currently prohibited from studying tribal citizens—at least until it finishes consulting with tribes—even for coronavirus antibody testing.

Given the tragic realities of this pandemic, health experts say addressing past ethical concerns and securing data rights in federal research institutions is crucial for both NIH and tribal nations to propel disease testing and research. Russo, who has been watching NIH’s tribal meetings closely, says institutions like NIH need to build better relationships and partnerships with tribal nations to help repair the damage of history’s mistakes. “The onus is on researchers and institutions, which fund them and support them, to change practices.”