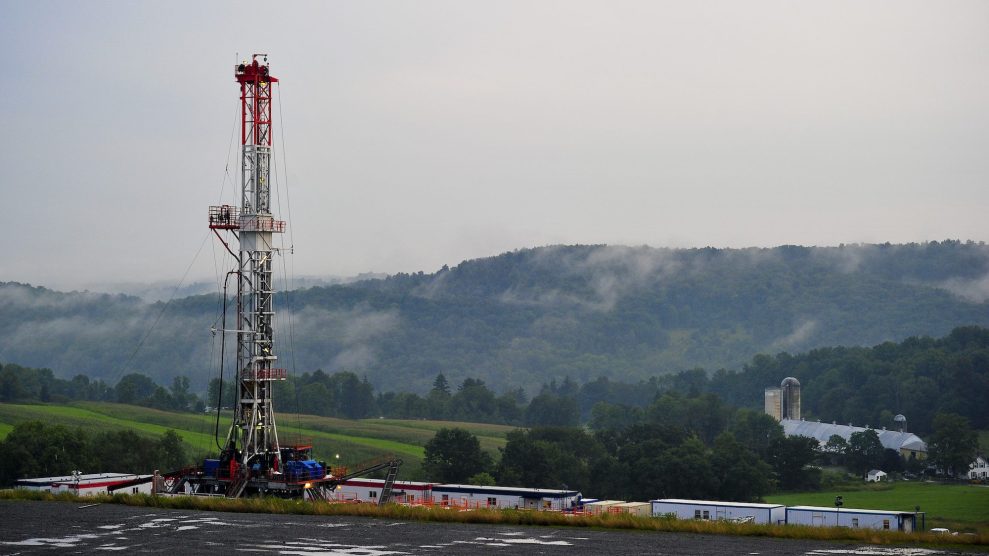

A natural gas well being drilled near Dimock, Pennsylvania.Charles Mostoller/Zuma

This piece was originally published in Grist and appears here as part of our Climate Desk Partnership.

My home state of Pennsylvania is always on the receiving end of some heavy pandering by presidential candidates: some feeble stabs at the Sheetz vs. Wawa convenience store debate, pointlessly coy hints at an allegiance with the Flyers or Penguins, a professed devotion to one hideous sandwich or another.

Generally, I can tolerate it. Part of the business of politics in general, and elections specifically, is to appeal to swing states using these kinds of caricatures. But the 2020 Pennsylvanian stereotype of choice perpetuated by Trump and Biden has not been so easy to stomach: that we Keystone State denizens are all wholehearted devotees of fracking.

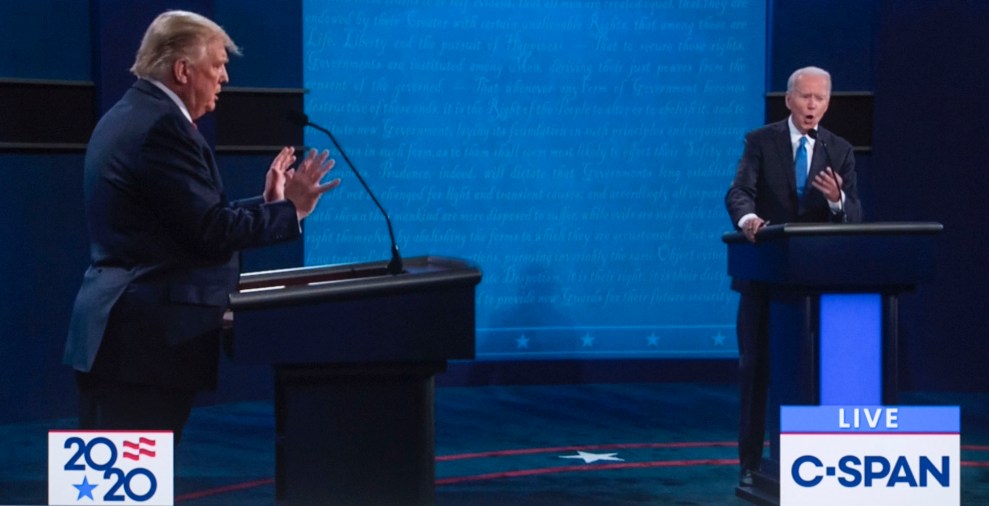

“If you want to kill the economy, kill the oil and gas industry,” Trump opined during Thursday’s final presidential debate, before launching into the usual accusations that his opponent will ban fracking. Biden denied it, but Trump warned ominously: “You know what, Pennsylvania, he’ll be against it very soon.”

You might be forgiven for assuming fracking is simply a synonym for “American industry,” as that’s how it’s used in a lot of political rhetoric. In actuality, it is a method of oil and natural gas extraction in which a concoction of chemicals and minerals are injected into tunnels drilled parallel to the ground. Pennsylvania, which rests atop the majority of the highly productive Marcellus Shale, does a great deal of it. We are the second-largest producer of natural gas in the country, after Texas. Moreover, we are the third-largest net supplier of energy, extracting more than four times what we consume.

The Trump-Pence campaign refers to fracking as if it were a sort of sacred ritual deeply meaningful to the identity of Pennsylvanians (and our 20 electoral college votes)—as if babies here are born with a drill clutched in one tiny fist and a seismograph in the other before being baptized in gasoline and Yuengling. On the national stage, fracking is celebrated via monologues by various working-class characters in ads, defended breathlessly by top-level Republicans who insist that Biden will ban it (again, he won’t), and praised at rallies in the heart of gas country.

But, like so many policies framed as concessions to swing states in the general election, neither candidate’s stance on fracking bears any strong resemblance to the complicated lives of people who actually have to confront it. Which was why, over several months last year, I headed out to talk to people who live near a proposed fracking well, on the site of the last functioning steel mill in the county.

The Edgar Thomson Steelworks is massive; it spans roughly a mile along the banks of the Monongahela River, and in doing so it touches four municipalities on the outskirts of Pittsburgh: Braddock, North Braddock, East Pittsburgh, and North Versailles (pronounced Ver-SALES, and you’ll get a puzzled look if you say it otherwise). Old mill towns run all up and down the Monongahela Valley, once considered extensions of the city, and this particular cluster sits just southeast of the city.

From an energy efficiency standpoint, the mill is an ideal site for a fracking well: Natural gas produced on-site could directly power the operation. But the bigger draw for residents of the region, of course, is a financial one. Whereas “fracking” has taken on all kinds of significance in the national conversation about everything from climate change to the economy, in a lot of Pennsylvania towns that never recovered from the loss of manufacturing or mining jobs, it just means “money.”

Unlike nearby Pittsburgh proper, there are no new, shiny condo developments and tech incubators in these chopped-up old mill towns. While the more affluent downtown neighborhoods of Lawrenceville, Bloomfield, and East Liberty are flush with employees of tech, medicine, and academia (and the money they bring with them), Monongahela Valley towns don’t have the kind of tax base or customer cash flow that Pittsburgh has increasingly enjoyed over the years. That’s why the lure of tax revenue from Merrion Oil and Gas, the company that’s proposed to put in a well on the site of the mill, is so appealing.

Allegheny County’s mostly urban makeup has spared it a lot of well development to date; you need specific zoning that’s rare in such a dense area to be able to drill. And these towns on the border of Pittsburgh don’t look much different from some of the neighborhoods within the city itself. The whole metro area is a hodgepodge of rusting warehouses and factories, lovely mansions, falling-down brick duplexes, new-ish taupe and neon strip malls, grand old libraries, museums, and schools—with so much lush greenery exploding out from the cracks in between.

One of the landowners that stands to benefit from the proposed well is the Grand View Golf Course, which is perched on the hillside overlooking the mill and the river, mostly because of the size of the property. Underground laterals from the well would extend under the expansive greens, yielding leasing revenue. The golf course itself has seen better days—by its own admission—but its high vantage point affords it a rather spectacular perspective of the little hillside houses across the river; the rollercoasters of Kennywood, the amusement park, on the opposite shore; and the mill itself, smoke billowing endlessly from its stacks.

Tom Beeler, manager of the golf course, expressed his support for the well in an email to Grist. “That money quite frankly is desperately needed to help keep the golf course—which is a centerpiece of the community and one of its biggest taxpayers—in business. Like many golf courses, we have been struggling for the past few years hoping that this project can help to turn us around.”

But for most residents, it’s not as straightforward a benefit: While income from oil and gas leasing has completely transformed the circumstances of some families in the region, it’s not likely to do the same for private property owners in North Braddock or East Pittsburgh. Lease agreements tend to be structured in terms of quantity of gas obtained per acre, and the small parcels of an essentially urban area don’t offer much of a payout. And to make matters worse, gas companies famously prey on cash-strapped families who will be too eager for an income stream to worry much about the terms of the lease.

“Some people are like, ‘Are you crazy? We need the money. This is our new and improved roads. New and improved infrastructure will bring income to the communities,'” explained Vicki Vargo, who’s on the borough council of North Braddock, in an interview last summer. “And other people go: ‘Yeah, are you crazy? Who in their right mind is going to want to live here?'”

In August of last year, Rep. Summer Lee, who represents North Braddock in Pennsylvania’s state congress, wrote in a letter opposing the development to the county health department: “This proposal would be the most urban setting that we have ever seen for a fracking well in Pennsylvania, exacerbating the aforementioned health effects.” The proposed well at Edgar Thomson would threaten the integrity of the (already flawed) drinking water, Lee alleged.

Disturbing clusters of rare cancers and birth defects have popped up in fracking-heavy regions of the state. The environmental historian Joel Tarr wrote that natural gas and oil wells polluting water sources in western Pennsylvania dates back to the 1800s, as sediment from the drilling process infiltrated water tables and abandoned wells were allowed to leak into the surrounding ecosystem.

While Pennsylvania has historically been a “fossil fuel state,” it’s not so clear that its actual residents want that cycle to continue. Approval and disapproval of the practice is split relatively evenly in the state, with a slightly higher percentage of the state in the latter camp. One might look at these divided numbers and simply attribute it to Pennsylvania’s cultural makeup, which tends to be split along geographical divides: “Philadelphia and Pittsburgh with Kentucky in the middle,” as the adage typically goes. (Sometimes people say “Alabama in the middle,” but you can really substitute any region that pundits might consider a “backwards,” truck-driving, tobacco-spitting, Republican-voting part of America.)

But the realities of fracking—from its geological impact to the jobs it might create—defy many of the themes hyped up by our current political system: urban vs. rural, jobs vs. nature, liberal vs. conservative. All kinds of borders blur when it comes to the impacts fracking has on a community. After all, municipal borders do not extend to air and water.

Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh and many of its abutting mill towns, is already in the top 2 percent of cancer risk from air pollution in the country. It’s important to note that this is not tied directly to fracking, but to the industry that fracked gas powers here. There is pollution from the steelworks, to be sure, as well as sometimes criminal particulate emissions from the Clairton Cokeworks in a town just a few miles down the valley. Even in high-rent Lawrenceville, there’s a steel foundry that can bring air quality down to very retro levels.

There’s conflict among the towns themselves about the virtues and risks of the well: North Braddock, for example, is less affluent than East Pittsburgh, and the latter has filed complaints against Merrion Oil and Gas, the company proposing to put in the well, for its failure to observe regulations. The town also just voted to reject an extension of the company’s permit; Merrion has declared that it will appeal the decision. And residents from all over the county gathered at a community meeting a year and a half ago to loudly resist the proposal — because, in the end, it’s more than just the towns that host the well that stand to be affected.

Even the most fervent environmentalist can end up drinking water tainted by the “slurry” of chemicals used in the drilling process one town over; a boutique farm-to-table restaurant in Pittsburgh can benefit from the patronage of a well-paid field engineer; and the perceived treasure trove of gas reserves lying underfoot might tempt any cash-strapped municipality or property owner, blue or red, into issuing a fracking permit of their own.

Trump and Biden have each tapped into one partial truth: There is an allegiance to old industry in some Western Pennsylvania families, a belief that the wealth that steel and coal and gas brought to the region, albeit years and years ago, is owed a certain respect. That no one’s family would be here, would have been able to establish homes and raise generations, without the jobs provided by the mills and the mines.

You can find a logical descendent of that allegiance in support of fracking, even though the modern incarnation of that industry is less magnanimous than the old, which isn’t saying much. There are no pensions provided by a year-long gig drilling a well, there are no promises of any semblance of security once that well inevitably dries up. Even for those who own enough land to benefit from oil and gas royalties, they are not worth as much as they were five-ish years ago, before a lot of wells were tapped and energy prices dropped. But in the absence of other opportunities, there is always a temptation to lean on the old crutch of the region’s prodigious fossil fuel reserves, even though all the risks of dredging up those old dinosaur bones are better known now.

“I just can’t get over this feeling that we cannot keep digging out the inside of the Earth without some consequence,” says Vargo. “I’ve been here all my life. I understand where people are coming from when they say, ‘Oh, so now all of a sudden the mill is bad.’ You know, my family benefited from a job at the mill, it’s not like I don’t appreciate that. What I don’t appreciate is the fact that at least three people in my family have bladder cancer.”

It’s the classic Faustian bargain of selling off any natural resource; you can have the money for the community, but there’s a chance you might taint the water and air and land so much that you drive the whole community away. That is, those who can afford to leave.

“My family grew up in Dooker’s Hollow, which is right by the mill,” Vargo said. “I’ve seen pictures of the early days before they were able to control some of the emissions and there was no vegetation. The hillsides were bare. What does that tell you? I mean, if even weeds don’t grow. What does that tell you?”

When the Western Pennsylvania gas wells drilled at the end of the 19th century began to run dry (as they inevitably do), a lot of homes and industries quickly returned to coal, which was how we ended up with the “hell with the lid off” black skies for which Pittsburgh is infamous. Today, natural gas is held up by many self-proclaimed “climate realists” as a “bridge fuel” in the opposite direction: part of the transition away from coal toward fossil fuel-free sources of energy, and that’s its own heated debate. It’s impossible to silo even the supporters of natural gas ideologically.

It’s a necessity of political campaigns, particularly national ones, to deal in generalities. You are trying to appeal to the most people possible in the fewest words. But when you describe Pennsylvania, with its population of 12 million individuals, as a monolith, referring to something as complex as fracking as a simple issue of good and bad, you fail to understand how fossil fuel development may have formed a backdrop for life in Pennsylvania for centuries now, but never defined it.

Election Day is nearly upon us, and while it may bring change, it is unlikely to mark a truly meaningful moment in the fracking debate for states like Pennsylvania. So it is here, at the juncture of four towns with different and increasingly pressing needs, on the edge of a city that wants little to do with them, that the very lengthy saga of siphoning gas from the Earth will continue as a real, living thing.