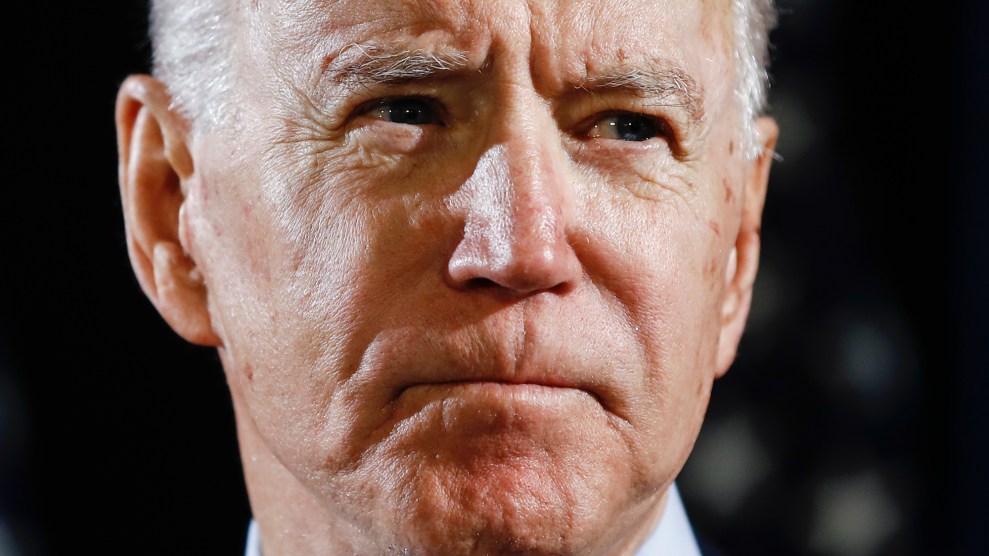

AP Photo, Matt Rourke

January 19, 2021: President-elect Joe Biden plans to sign roughly a dozen executives orders on his first day in office, including rejoining the Paris climate accord. The United States will officially be back in a month later, in February. Then comes the hard part: Not only will Biden have to resubmit a new domestic target for 2030 US greenhouse gas emissions, but he will have to back those promises with longer-term congressional action and financing for international causes.

Today, two world-changing events collide. The day after a nail-biter of a historic election, the United States became the only country to back out of the Paris climate change agreement. After the required waiting period, on Wednesday, President Donald Trump officially followed through on a threat he has been making since his first campaign to pull the United States out of the accord. This is a big deal: The Paris agreement marked a breakthrough in bringing rapidly growing nations like China and India under the same terms as the historically worst polluters, like the United States and Europe, as time is running out to contain global warming.

One silver lining: Not a single country has followed the United States’ lead yet to exit the agreement. In fact, 38 more countries have joined since Trump’s announcement in 2017. Yet many of the ominous predictions experts made when Trump first announced his intention to withdraw three years ago are holding up. I wrote then that Trump had no sense for the backlash in store for the United States for his isolationist foreign policy:

Two factors will especially hurt the US: First, the world has been dealing with the US as an unreliable partner on climate change for more than two decades, and leaders still well remember the other times the US reversed course on its promises; second, the world has never been more aligned in favor of action, making climate change a much bigger factor in the US relationship with its allies in non-climate related issues—from trade to defense to immigration—than it once was.

In a New York Times op-ed in 2017, George Shultz, a former Cabinet member of the Reagan and Nixon administrations, and Climate Leadership Council’s Ted Halstead begged Trump to remain in the accord. They predicted that Trump would create a power vacuum with global-level consequences. “If America fails to honor a global agreement that it helped forge,” they wrote, “the repercussions will undercut our diplomatic priorities across the globe, not to mention the country’s global standing and the market access of our firms.”

That has proven accurate: Without Trump, countries have forged ahead with domestic climate action. European nations and China have sought to fill the vacuum left by the United States. Now, China, India, and Europe have shown their appetite for strengthening their initial clean energy goals, while Trump has continued to talk about reviving the fast-declining coal industry.

If Joe Biden wins the election, he has promised to re-enter Paris on Jan. 20th next year, which will take effect one month later. Then, things get complicated.

“Rejoining Paris—that would be the easy part,” Alden Meyer, an independent expert who has 30 years of experience in international climate policy and science. “The harder part would be delivering the goods.” After joining Paris again, Biden would have to resubmit a new emissions target, which experts expect would initially look modestly similar to where Obama’s targets once were. But the United States needs to go even further to prove it’s serious about permanent changes to create a low-carbon economy. Biden would also need to put money where his mouth is by finally delivering on the United States’ $3 billion commitment to the Green Climate Fund, an international pot of money to help developing countries counter climate change. His first task would be to come up with the remaining $2 billion that Trump reneged on.

How much further Biden would be able to press global climate action depends heavily on which party controls the Senate. The president can pressure other countries to reduce foreign investments and exports in coal, and he can use the Environmental Protection Agency’s existing powers to slash carbon emissions. But the most ambitious, fastest timeline for doing anything requires laws passed by Congress.

“The Senate matters a lot because all the analyses shows that using existing authority under the Clean Air Act and energy legislation with executive agency action, you get the United States somewhere maybe in the 30 to 32 reduction range [by 2030],” Meyer says. “But to get closer to the 40 to 50 percent range that science and equity at a minimum demands, it would be hard for the United States to get past that benchmark through executive action alone.”

Congress matters for another reason, too: The world has understandably lost faith in the continuity of US politics on climate change. Congressional action on climate would provide some assurance, Meyer says, that “we’re not going to be on a rollercoaster of policy changes administration to administration.”