Old Faithful at sunset. As water reserves decline, the geyser is expected to erupt less frequently.Neal Herbert/National Park Service

This story was originally published by Yale E360 and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In 1872, when Yellowstone was designated as the first national park in the United States, Congress decreed that it be “reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, and sale and … set apart as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” Yet today, Yellowstone—which stretches 3,472 square miles across Montana, Wyoming and Idaho—is facing a threat that no national park designation can protect against: rising temperatures.

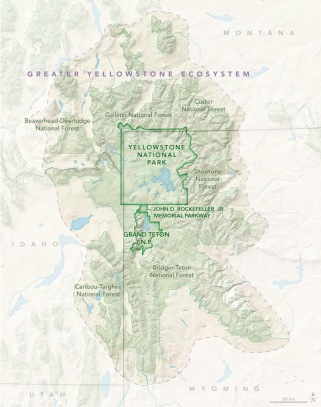

Since 1950, the iconic park has experienced a host of changes caused by human-driven global warming, including decreased snowpack, shorter winters and longer summers, and a growing risk of wildfires. These changes, as well as projected changes as the planet continues to warm this century, are laid out in a just-released climate assessment that was years in the making. The report examines the impacts of climate change not only in the park, but also in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem—an area 10 times the size of the park itself.

The climate assessment says that temperatures in the park are now as high or higher as during any period in the last 20,000 years and are very likely the warmest in the past 800,000 years. Since 1950, Yellowstone has experienced an average temperature increase of 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit, with the most pronounced warming taking place at elevations above 5,000 feet.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

NASA Earth Observatory map by Joshua Stevens, using data from the National Park Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service

Today, the report says, Yellowstone’s spring thaw starts several weeks sooner, and peak annual stream runoff is eight days earlier than in 1950. The region’s agricultural growing season is nearly two weeks longer than it was 70 years ago. Since 1950, snowfall has declined in the Greater Yellowstone Area in January and March by 53 percent and 43 percent respectively, and snowfall in September has virtually disappeared, dropping by 96 percent. Annual snowfall has declined by nearly two feet since 1950.

Because of steady warming, precipitation that once fell as snow now increasingly comes as rain. Annual precipitation could increase by 9 to 15 percent by the end of the century, the assessment says. But with snowpack decreasing and temperatures and evaporation increasing, future conditions are expected to be drier, stressing vegetation and increasing the risk of wildfires. Extreme weather is already more common, and blazes like Yellowstone’s massive 1988 fires—which burned 800,000 acres—are a growing seasonal worry.

The assessment’s future projections are even bleaker. If heat-trapping emissions are not reduced, towns and cities in the Greater Yellowstone Area—including Bozeman, Montana and Jackson, Pinedale, and Cody, Wyoming—could experience 40 to 60 more days per year when temperatures exceed 90 degrees F. And under current greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, temperatures in the Greater Yellowstone Area could increase by 5 to 10 degrees F by 2100, causing upheaval in the ecosystem, including shifts in forest composition.

At the heart of the issues facing the Greater Yellowstone Area is water, and the report warns that communities around the park—including ranchers, farmers, businesses and homeowners— must devise plans to deal with the growing prospect of drought, declining snowpack and seasonal shifts in water availability.

“Climate is going to challenge our economies and the health of all people who live here,” said Cathy Whitlock, a Montana State University paleoclimatologist and co-author of the report. She hopes “to engage residents and political leaders about local consequences and develop lists of habitats most at-risk and the specific indicators of human health that need to be studied,” like the connection between the increase in wildfires and respiratory illness. Sounding the alarm isn’t new, but the authors of the Yellowstone report hope their approach, and the body of evidence presented, will convince those skeptical about climate change to accept that it’s real and intensifying.

The report describes a scenario that is now all too common across the American West and in the region’s renowned national parks, from Grand Canyon in Arizona, to Zion in Utah, to Olympic in Washington state. Record warming and extreme drought mean there is not enough fall and winter moisture, leading to steadily declining mountain snowpack. Many iconic venues may soon lose the very features they were named for. Most striking is Glacier National Park in Montana, where, since the late 19th century, the number of the park’s glaciers has declined from 150 to 26. The remaining glaciers are expected to disappear this century.

In Joshua Tree National Park in California’s Mojave Desert, extreme heat—coupled with a prolonged drought—has wreaked havoc on the eponymous species. Because of drought and wildfire, the park is poised to lose 80 percent of its renowned Joshua trees by 2070.

Swaths of Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado have suffered massive die-offs of white pine and spruce as warming-related bark-beetle infestations have killed an estimated 834 million trees across the state. And in Yosemite National Park in California, the rate of warming has doubled since 1950 to 3.4 degrees F per century. Yosemite is experiencing 88 more frost-free days than it did in 1907. The park’s snowpack is dwindling. Its remnant glaciers are fast disappearing. And wildfires are becoming more common. In 2018, the park was closed for several weeks because of dense smoke from a fire on its border. The National Park Service says that temperatures could soar by 6.7 to 10.3 degrees F from 2000 to 2100, with profound impacts on the Yosemite ecosystem.

Yellowstone River. Snowpack in the Yellowstone area is melting earlier, leading to a decline in summer streamflows.

Jacob W. Frank/National Park Service

The Yellowstone assessment paints a detailed portrait of the past, present and future impacts of climate-related changes.

“This is one of the first ecosystem-scale climate assessments of its kind,” said co-author Charles Drimal, water program coordinator for the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. “It sets a benchmark for how the climate has changed since the 1950s and what we are likely to experience 40 to 60 years from now in terms of temperature, precipitation, stream flow, growing season and snowpack.” Researchers from the US Geological Survey, Montana State University and the University of Wyoming were the lead scientists on the report.

The report’s study of snowpack and its link to water offer the biggest takeaways for Westerners who might question how or why they’re impacted. Rocky Mountain snowmelt provides between 60 to 80 percent of streamflow in the West, and hotter temperatures mean reduced snowfall and less water for cities as far afield as Los Angeles. For the millions of people living in cities across the West, many of whom are reliant on runoff from the snowpack in the Rocky Mountains, these trends jeopardize already insufficient supplies. The dangers are starkly evident this summer, as years of drought and soaring temperatures have left the West facing a perilous wildfire season and water shortages, from Colorado to California.

“All that snow becomes water that goes into the three major watersheds of the West—some of it goes as far as L.A.—and that comes together in the southern edge of Yellowstone National Park,” said Bryan Shuman, a report co-author and geologist at the University of Wyoming. “Looking at projections going forward, that snowpack disappears.”

The Yellowstone, Snake and Green rivers all have headwaters in the Greater Yellowstone Area, feeding major tributaries for the Missouri, Columbia and Colorado rivers that are vital for agriculture, recreation, energy production and homes. Regional agriculture—potatoes, hay, alfalfa—and cattle ranching depend on late-season irrigation, and less snow and more rain equals less water in hot summer months.

Then there are the rapidly growing tourism and hospitality industries that rely on Yellowstone’s world-class rivers and ski areas for angling and black diamond runs. Fishing is now regularly restricted because of high water temperatures that stress fish.

“Even mineral and energy resource extraction need to be part of this discussion,” said Whitlock, referring to Wyoming’s oil and gas industry, heavily reliant on large amounts of water. Industry may be the slowest to evolve, but it’s among the most at-risk, she said.

Many locals do quietly acknowledge the reality of what’s happening, she said, but community buy-in remains tough in this culture war hotspot, where many farmers and ranchers have long opposed government land intervention.

The land in the Greater Yellowstone Area, comprising 34,000 square miles, is among the last, largely intact temperate ecosystems in the United States and includes two national parks (Grand Teton in Wyoming is the other), five national forests, and half a dozen tribal nations. It’s also home to 10,000 hydrothermal features, including 500 geysers. Recent research has shown that in periods of extreme heat and drought, geysers such as Yellowstone’s renowned Old Faithful have shut down entirely.

The current conditions do have some historical precedent. In the last 10,000 years, Yellowstone has experienced periods of dryness equal to or greater than present, said Whitlock.

Electric Peak in Yellowstone National Park. Snowfall in the Yellowstone region has declined as a result of climate change.

Neal Herbert/National Park Service

“That’s a lens to look at the past,” said Shuman, who once trekked the 3,000-mile Continental Divide Trail to get a sense of the land. “If you add just a few degrees, you fundamentally alter things. When you walk across these high mountains, you can see they used to be covered in glaciers. It’s like walking in the ruins of Ancient Rome. That Ice Age world was only 5- to 7-degrees F colder than the pre-industrial era.”

“The water in those mountains is the water supply of the West and it’s drying up,” said Shuman.

In Yellowstone, the threat to human health and livelihoods may be the strongest incentive to take steps to soften the blows from climate change.

“Water is the thing everyone is most concerned about, and in general, people are receptive,” said Shuman. “Our economic future depends on adjusting.”

Just how the residents of the Greater Yellowstone Area will adapt is an open question, but researchers say that acknowledging the myriad problems that are now daily realities for many, from ranchers to anglers, is the first step toward a productive dialogue.

As the West experiences a growth surge, Cam Sholly, Yellowstone National Park’s superintendent, writes in the report that “the strength of local and regional economies” hangs in the balance if no steps are taken to rein in global warming.

Said Whitlock of Montana State, “When you think about the temperature curve that looks like a hockey stick, my parents pretty much lived on the flat part of the curve, I’m on the base, and my grandkids are going to be on the steep part. Our trajectory depends on what we do about greenhouse gases now. By 2040, 2050, we can flatten the curve. But the business-as-usual trajectory, 10 to 11 degrees of warming in Yellowstone and much of the West—what we do in the next decade is critical.”