The Dixie Fire burns in Susanville, California, on August 17, 2021.Ty O'Neil/SOPA

When a forest is torched by wildfire, what’s left behind is something resembling a dystopian hellscape. There are no green things, just a carpet of scorched earth and telltale piles of ash and debris: Here was a house, here a garden, here the shell of a car—and thousands of trees, stripped and blackened. It feels postapocalyptic, this flora-less wasteland. When the skies turn a burnt orange, Blade Runner 2049 doesn’t seem off base.

California’s runaway wildfires have been a harbinger of climate change that’s impossible to ignore—the heartbreak of each new season’s losses of homes and communities, the months of tainted air in portions of the state, the shattering of records for acreage burned. Fire has disrupted life for many residents and has raised questions about the longevity of the state’s iconic landscapes.

Already, California trees are threatened by drought and warming temperatures. By 2100, according to one projection, Joshua Tree National Park could lose the ability to host its Seussian namesake. California’s soaring redwoods and sequoias, too, face habitat loss. To save imperiled trees in California and elsewhere, scientists are even looking to assisted migration—the movement of organisms beyond their usual habitats—to help various tree species survive changing climate conditions.

But while recent fires have been more severe than those in the past, the associated harm has more to do with human priorities than the health of the forests themselves. Fire generally isn’t damaging to forests. On the contrary, it plays a restorative function. The perception that fire is bad originated with colonialism, when forests became a source of profit, and fire suppression disrupted the natural processes of forest ecosystems.

“California forests are fire-adapted, which means they need fire to thrive,” says Crystal Kolden, an assistant professor of fire science at the University of California, Merced. “Precolonization, much of California’s forest would burn every five to 20 years.”

What we’re seeing now is the reintroduction of fire to forests that haven’t been allowed to burn for more than a century. These megablazes, Kolden says, are “doing the work that fire has done for millennia—taking out a lot of old dead material, thinning out the forest naturally and reinitiating that biogeochemical cycle that breaks down all the vegetation and returns those nutrients to the soil.”

The threat isn’t so much the destruction of trees as the impacts on human communities, says Chad Hanson, director and ecologist at the John Muir Project: “In a nutshell, what I can tell you is that our forests have always had a mix of fire intensity—low, moderate, and high—that’s natural, and it’s good. You need that.”

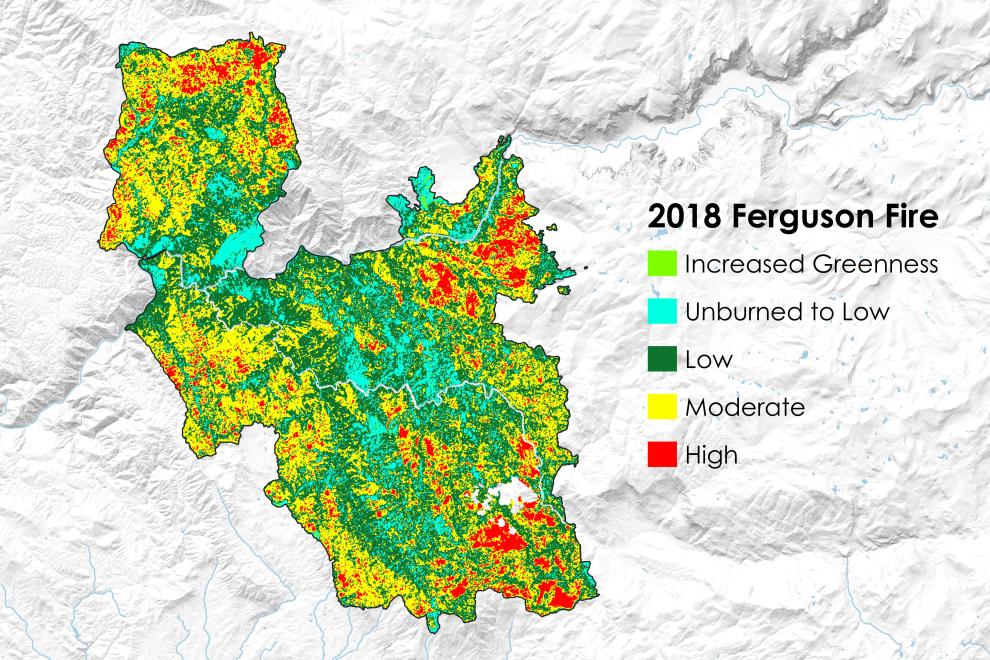

Map of the 2018 Ferguson Fire’s burn severity.

Bryant Baker/Los Padres ForestWatch

Policymakers and people who live in fire-prone areas are only recently catching on to what Native Americans have understood for centuries. Some scientists and foresters have been pushing for decades to incorporate fire into the process of land management, but bureaucratic gridlock has largely prevented it. “The key thing to understand,” Hanson says, “is that even when we have big fire years, like this year and last year, sometimes we still have less fire overall in our forests than we did naturally before fire suppression.”

The media zeroes in on the disaster aspect of big blazes, a habit that has cemented the idea that fire is bad. “Often what the public sees in the media is a completely destroyed landscape where it’s basically a moonscape with some black sticks sticking up. That’s high severity fire. And there is some of that on all of these fires,” Kolden tells me.

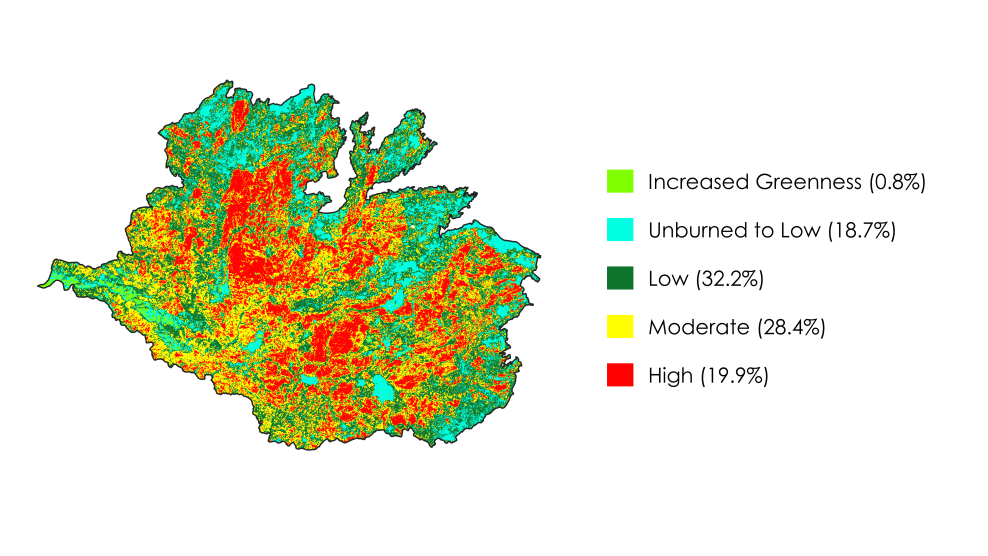

High-severity fire—which burns hot enough to consume more than 75 percent of trees in a given area—is also part of the forest ecosystem. Typically, those portions of a fire leave behind “snag forest habitat”—which Hanson says is such an abundant ecosystem that it rivals old growth forest in the richness of biodiversity and wildlife. While you want some high-severity fire, you don’t want most or all of a given conflagration to look like that, he says. About 20 percent of the typical wildfire burns hot enough to create snag forest. (High-severity fire can cause other problems, such as landslides and watershed pollution.)

Snag forest 8 years after the 2013 Rim Fire.

Bryant Baker/Los Padres ForestWatch

But with rising temperatures and chronic drought in the West, “very, very high severity” burns make the landscape’s future less certain, Kolden says. A hotter climate might prevent trees from regenerating in some areas; researchers are keeping an eye on burn zones in places like the southern Sierra Nevada and the Cascades to see how those forests respond.

Some forest will never recover, Kolden adds. But that doesn’t mean they will remain barren and lifeless. There’s a myth that fire burns so hot in some places that it prevents life from regenerating—destroying soil and plants and leaving a wasteland behind. But fire ecologists deny this. “That’s a narrative that’s out there,” Hanson says. “I can tell you that doesn’t exist. I’ve been researching large high-intensity fires in the western United States for 20 years, and I’ve never found a single acre where that’s true. Not a single acre.”

California may look different in the future, however. We can expect to see fewer of some species of trees and more of others. “Conifers that are better able to withstand drought and deal with these drier conditions—those may become more dominant,” says Bryant Baker, conservation director at Los Padres ForestWatch. “Hardwood species that are a little bit hardier, like oaks—you may see that those become a little bit more prevalent. You may see that the ecosystem starts to become a little bit more spread out.

Map of burn severity on the 2013 Rim Fire.

Bryant Baker/Los Padres ForestWatch

These shifts are how nature adapts, he says. “We have got to get climate change under control, we’ve got to reverse what is happening. Until then, there are going to be things that we just simply have to recognize. These ecosystems are going through their own adaptive processes. And there’s not much we can do about that.”

But the future isn’t set in stone. “The thing I always do when I start to sort of lose hope is I go talk to my Indigenous colleagues,” Kolden says, “and they’re like, ‘No, you know what, we can fix this problem. We have the knowledge to fix this problem passed down to us through the generations.’”

The complicated truth is that forests still need fire—so we need it, too, Kolden says: “Now it’s our job to go in and say, ‘We screwed up for 100 years. Now we’re going to look at this differently and try and manage this forest to be resilient going ahead.’”