Students stage a halftime sit-in at the 2019 Yale-Harvard football game to protest their schools' oil and gas investments.Associated Press

This story was originally published by Slate and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Harvard University’s September decision to stop investing in fossil fuel companies, and to let its current investments in the sector expire without renewal, was widely hailed as one of the biggest climate victories in recent history. And for good reason—it was the most significant win yet for the climate divestment movement, a decade-old initiative that’s applied a popular anti-apartheid activist tactic to get colleges, banks, charitable foundations, and religious organizations to stop funding oil and gas firms. Harvard has the largest endowment of any university in the world—totaling $53 billion—meaning a deep pool of money is now out of Big Oil’s reach. This mission was also primarily driven by Harvard’s students; campus group Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard employed moves from meeting directly with administrators to storming the field during the annual football game against Yale. It’s all quite literally paid off.

Yet, as is the case with any successful social initiative, there’s now an institutional backlash. As Kate Aronoff has reported in the New Republic, the American Legislative Exchange Council—a Koch-linked nonprofit that helps state legislators craft right-wing policy—is writing model bills to protect fossil fuel investments, in essence making divestments like Harvard’s illegal. Their framework prohibits “discrimination” against fossil fuel companies by requiring state treasurers and comptrollers to withdraw government funds from banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and other financial institutions that “boycott” investing in oil and gas firms. Texas is the only state so far to have such a policy on the books, but states like West Virginia have considered similar legislation.

At this point, numerous institutions have already successfully disinvested in fossil fuels, yanking a total of $40 trillion from the industry’s reach so far. But if ALEC has its way, with the support of sympathetic red states and conservative legal scholars, it could strike a blow to one of the climate movement’s most effective tools. For now, the bills at play seem to target private businesses, but scholars have outlined ways universities’ divestment efforts could hypothetically face legal trouble, as well. Other academic institutions, like Boston College, are putting up fights to resist divestment pressure.

To take stock of the successes of climate divestment so far, and to assess the challenges that lie ahead, I spoke over Zoom with Connor Chung, a Harvard Class of 2023 student who was on the field for that famous football game and has been closely involved with Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard ever since. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Nitish Pahwa: How did you get involved in Harvard’s divestment campaign?

Connor Chung: As I got situated on campus my first year, it was both amazing to be part of the Harvard community and really quite painful to learn that the school was actively working against my and my peers’ future through its multitude of investments in the fossil fuel industry. To make matters worse, it wasn’t clear that they even wanted to meaningfully listen to young people. It’s in part with that in mind that I decided to get more involved, my freshman year, in the fossil fuel divestment movement.

The divestment movement works on two key prongs. There’s the economic prong of cutting off the flow of money that the fossil fuel industry needs to finance the status quo—and there’s clear evidence that this works. Even fossil fuel companies have admitted it in disclosures to regulators. The other prong is as a social tactic, mobilizing people, raising awareness, revoking the industry’s social license. It’s the idea that, if it’s wrong to wreck the planet, it’s wrong to try to profit from that destruction.

Divestment has emerged as one of the most potent material threats to the fossil fuel industry. For years, the fossil fuel industry has sought to diffuse the divestment movement by claiming that it doesn’t work, that it makes no material difference whatsoever. Yet despite the confidence of their public pronouncements, these very industry workers have been freaking out behind the scenes and spending ungodly sums of money to defeat the movement. For a while, whenever our group would put out a press release to the rest of Harvard, there’d be a website run by an industry trade group and a PR firm that would issue a response to us. We found it absolutely hilarious to imagine some poor person spending their day at the office having to respond to a bunch of things some college students wrote at 3 a.m.

Is there a particular tipping point you think that is convincing institutions to finally get behind divestment? Or, in your experience, did you find there was one particularly persuasive argument that got Harvard on the side of divestment?

One reason the divestment movement has proved so successful is because it forces powerful institutions to choose which side they’re on. Around the world, young people are demanding environmental justice and climate action, and they’re following the money to see who’s serious. These past 10 years, the moral and the financial arguments have become all the more clear. Back then, activists were warning that fossil fuel investments posed a profound and unmitigable risk to a portfolio, that they were not a good way to make money, and that it was deeply misguided to invest in the arson as the planet burns, so to speak. Those predictions have borne out: Fifty years ago, fossil fuels were, I believe, about a quarter of the S&P 500. Today, they’re under 3 percent. Over the past decade, it’s proved to be one of the worst sectors you could have invested in.

Just on the economics, oil prices did go subzero at one point in 2020, but then they sharply rebounded through 2021.

Some of the fluctuation is expected, but it’s simply not reversing long-term trends. If you had invested a buck in the fossil fuel industry 10 years ago, versus in pretty much any other sector of the S&P 500, that fossil fuel dollar would be among the worst-performing, even taking into account recent fluctuations.

Broad swaths of these companies’ assets stand to be rendered unburnable if we are to meet global climate agreements, meaning that what we’re seeing now may be only the tip of the iceberg.* When it comes to climate risk, financial actors have moral and legal requirements to act responsibly and judiciously. Fossil fuels are simply hard to square with this.

Recently, the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, which does fascinating research on the energy transition, produced a report that shows divestment has no negative financial consequences—it oftentimes leads to financial gain for those who take that path. So I think we’re seeing that being a dinosaur does not pay. So the financial argument for divestment is exactly where activists said it would be 10 years ago.

There’s been some recent reporting about how ALEC, which has countered environmental action for decades, is now working on establishing legislative frameworks for bills that would punish institutions that try to divest their funds from fossil fuels. Those are in the beginning stages, but the anti-climate movement, as always, is looking at the long game here. I’m wondering what you think is the best path forward in addressing this move.

First of all, it’s deeply counterproductive. Conservative states are some of the ones that’ll bear the greatest burdens from climate impacts. So by pushing policies that’ll lead to hurting people’s pocketbooks, hurting state’s bottom lines, and exposing everyone to more climate risk, they’re shooting themselves in the foot.

There’s a long history of fossil fuel companies being anti-divestment because they know what kind of a threat to their vision for the future. ALEC has of course taken funds from many of the largest fossil fuel companies, it’s long been responsible for trying to avoid climate action, and, by pursuing this course of action, it’s only providing more proof that divestment works. So, this is nothing new.

But to your broader question, what is the fossil fuel divestment movement doing to make sure things stick? One answer is that it’s increasingly turning to the legal system to push for change. In March, our campaign worked with attorneys at the environmental protection nonprofit Climate Defense Project, to file an official complaint with our state attorney general, arguing that Harvard’s fossil fuel investments weren’t just immoral but also illegal. There’s a law, the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act, that lays out the fiduciary expectations for a nonprofit investor like Harvard.

We argued that these mandates are simply failed by fossil fuel investments. Our complaint was backed by everyone from former Harvard governing board members to one of the legal scholars that helped write the state law in question. That was absolutely influential in winning divestment at Harvard. When our university announced divestment, in their email, they all quoted the language of our complaint about the fiduciary needs for divestment.

There have been more complaints filed, against the University of New Mexico, Boston College, Johns Hopkins, and others. The beauty of these complaints is not just that they’re putting significant pressure on these schools, but they’re also working to create a shift in the law nationwide. The laws governing fiduciary duties and prudent investor standards are remarkably similar across states. So precedent is beginning to reflect the fact that fossil fuel investment is not just immoral but also unacceptably risky from a fiduciary perspective.

Do you foresee any trouble for the divestment movement taking the legal route, since the conservative legal movement has captured courts at the state and federal level?

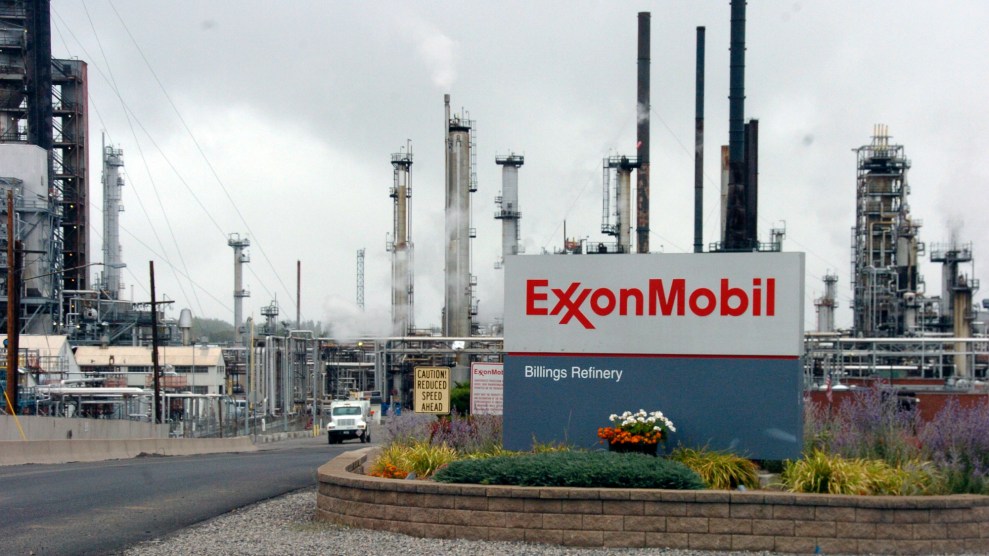

I think anti-climate interests have done a remarkably good job over the years of understanding the inner workings of powerful institutions, whether the legal system or universities, and, as a result, have gotten really good at exploiting them. It’s not just the court system that’s stacked with fossil fuel lawyers, for example. Look at Harvard’s own governing board—one of its members is Ted Wells, one of Exxon’s top lawyers.

So I think it’s really important that those seeking a more just and stable future rise to the challenge and not let these institutions’ paths solely be dictated by fossil fuel interests. This fight for the future is and should be taking place on all fronts, as I see it. Not using any tool at our disposal would be a shame. The good news is: The climate movement is increasingly recognizing this and working to take back that power and deploy it for good.

Speaking of, your group wrote a report about how the next step now is addressing other Harvard staffers, board members, and various affiliates who have fossil fuel ties, and who are in any sort of position to influence Harvard’s stance on climate action.

Our group remains committed to continuing to end Harvard’s fossil fuel ties. For one, that looks like holding Harvard accountable to its commitment and pushing for reinvestment of the endowment as an active force for good. Two, talking about the conflicts of interest between Harvard and the fossil industry. Out of the momentum created by the success of divestment, we’ve seen movement in recent years to push beyond investors—to get Big Law and Big PR, for example, to sever their fossil fuel ties. The financial sphere is one of only many ways in which entrenched interests prop up fossil fuels.

A talking point that has been emerging with the success of divestment, and with the rise in so-called climate finance and shareholder activism, says private action will be the solution to the climate crisis, versus public policy, which has been stalling, and administrative action, which has been mixed. I’m wondering what your thoughts are on that.

I think you’re right in that there are a lot of entrenched interests that are holding back climate action. The climate crisis is, in many ways, a crisis of democracy. It’s not that people don’t want climate action—people want things like clean air and good jobs. It’s that there are interests dedicated to holding that back. Ultimately, I think action via public channels and action via private channels are mutually complementary: An environment in which public policymakers are more willing to take dramatic climate action enables others to make a difference, and a world in which private interests are held to account and forced to pick which side they’re on builds support for things like public policy. Climate activism sits in the middle of all of this. As regular people, we’re in the public interest and private interest and everything in between.