Just Stop Oil/ZUMA

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

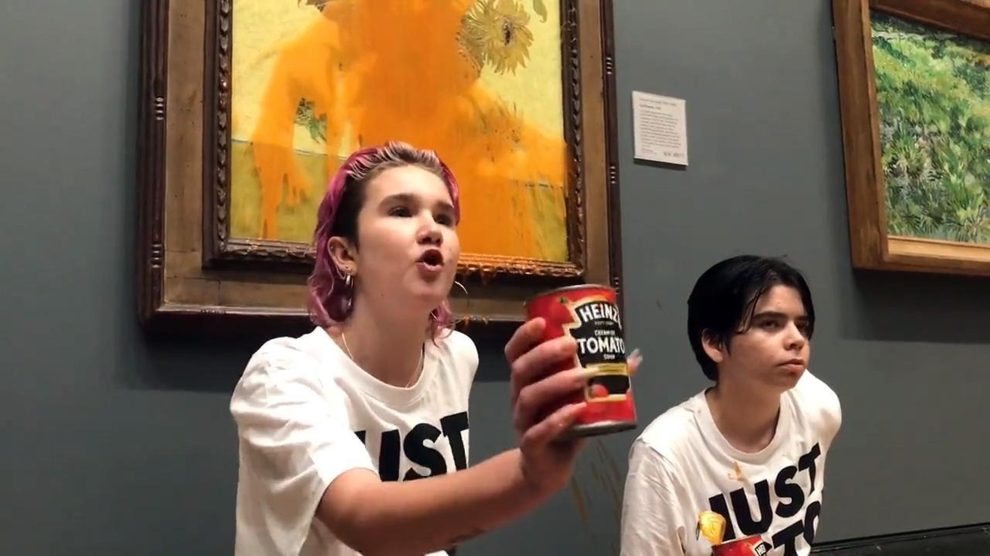

The US funders of a climate activist group that poured tomato soup over Van Gogh’s Sunflowers at the National Gallery in London have vowed similar attention-grabbing stunts will take place in various countries in the weeks ahead.

On Friday, two young activists from the Just Stop Oil group entered the gallery, opened two tins of Heinz tomato soup and hurled them over the painting, which is protected by a pane of glass. As onlookers exclaimed “Oh my gosh!”the activists glued themselves to the wall beneath the painting. “What is worth more, art or life?” said Phoebe Plummer, one of the activists.

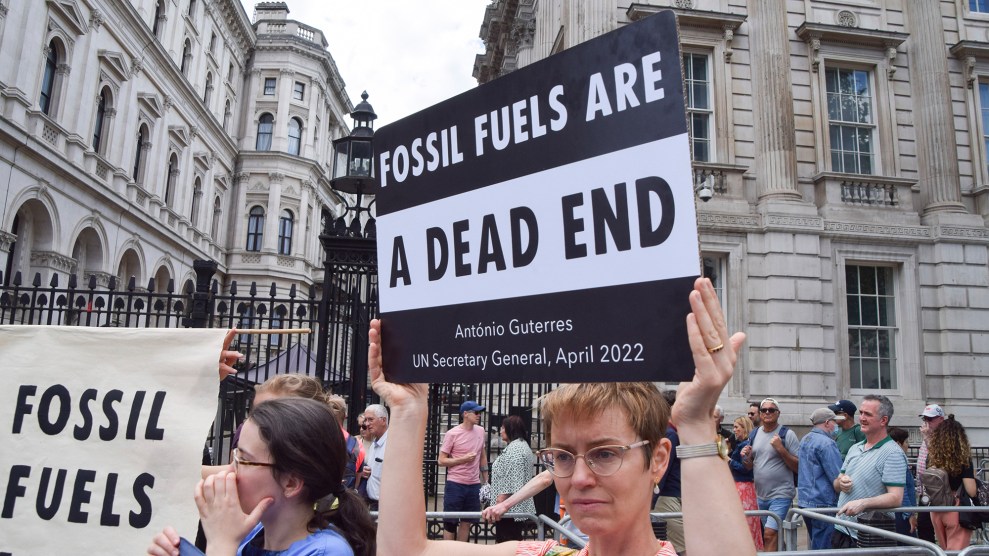

The protest, which has drawn applause and sharp criticism, is just the latest one bankrolled by the Climate Emergency Fund, a US network set up in 2019 to fund dramatic forms of protest in an attempt to spur action on the climate crisis. The organization said it will seek to build on the shock of the Van Gogh souping to support further protests across Europe and the United States.

“More protests are coming. This is a rapidly growing movement and the next two weeks will be, I hope, the most intense period of climate action to date, so buckle up,” said Margaret Klein Salamon, executive director of the Climate Emergency Fund. “In terms of press coverage, the Van Gogh protest may be the most successful action I’ve seen in the last eight years in climate movement. It was a breakthrough, it succeeded in breaking through this really terrible media landscape where you have this mass delusion of normalcy. It’s time to wake up.”

The Climate Action Fund has handed out more than $4 million to dozens of climate organizations this year (Just Stop Oil is the biggest recipient, receiving $1.1 million), helping trigger a wave of unusual protests across Europe. Activists have glued themselves to The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci in London and an Umberto Boccioni statue in Milan, damaged fuel pumps, rushed on to the track of the British Grand Prix, and even been zip-tied to a goal post during a Premier League game between Everton and Newcastle.

These striking protests are even more remarkable in that they have been funded in part by an oil heiress. Aileen Getty, a philanthropist whose grandfather was the tycoon J Paul Getty, co-founded the Climate Action Fund and has gifted it $1 million to be used by activists. Among thousands of other smaller donors to the fund, several other prominent figures have made major contributions—Abigail Disney, scion of the Disney family, has given $200,000 and Adam McKay, director of the darkly satirical climate film Don’t Look Up, has pledged $4 million.

The money is used to pay and help train people via the activist groups, seeding acts of civil disobedience that Salamon argues are echoes of previous eras, such as the civil rights movement or the suffragettes. “We are helping wealthy people who are freaked out by climate change, because we all live on this planet, to fund the most effective activism possible,” she said. “The activists have forced millions of people who don’t want to think about the climate emergency to think about it. No one is protesting art or sports, but the point is the house is on fire, this is an emergency. We can’t just enjoy beauty and fun and continue as we are while doing nothing about it, because at the moment we are accelerating off a cliff.”

Just Stop Oil’s dousing of Sunflowers has attracted plenty of criticism, with some decrying it as vandalism (although only the frame was slightly damaged) or questioning the relevance of the painting to the need to shift away from fossil fuels. Tucker Carlson, the right-wing Fox News host, called the protestors “radicals” and “religious extremists”.

“Merely getting publicity for a cause doesn’t automatically translate into generating support for it,” tweeted Paul Graham, the prominent investor. “If you get publicity for a cause in an obnoxious way, you’ll generate opposition to it.”

Theories have even been spread on social media that the stunt was aimed at discrediting climate activists, as part of an elaborate ruse concocted by Getty. “That just seems unfair to me,” said Salamon of Getty’s involvement. “You can’t hold someone responsible for the sins of their deceased grandfather. She’s doing everything to make it right—what would you rather her do, just go off and live a life of luxury?”

Supporters of this funded activism point to research showing that disruptive tactics can motivate those more moderately supportive of a cause, while causing little backlash from others, a so-called “radical flank effect” that has seen a youth climate movement blossom amid everything from school strikes, spearheaded by the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, to the mass deflation of SUV tires.

“This was the tomato toss heard around the world,” said Dana R Fisher, a sociologist at the University of Maryland who studies climate protest. “The target wasn’t art. It was using art as a platform, and it caught the attention because it used a tactical innovation: tomato soup.”

Fisher said it was uncertain yet how effective the protest will be. “I’m sure it will turn some people off,” she said. “But the idea isn’t to win over hearts and minds, it’s to grab media attention and mobilize people who are sympathetic to the cause.”

Climate campaigners often complain that holding the public’s focus on global heating can be challenging, despite a growing parade of climate-driven disasters and an increasing sense of despair, particularly among younger people, over inaction by governments. Since 2019, two American men have self-immolated in separate incidents aimed at raising awareness of the climate crisis, although neither act gained as much attention as the Van Gogh incident.

The latest stunt by Just Stop Oil has “revealed that a huge number of people feel more outrage at a painting getting splattered with soup than they do with the irreversible and intensifying destruction of life on Earth,” according to Peter Kalmus, a Nasa climate scientist who handcuffed himself to a bank in Los Angeles earlier this year.

“It’s really quite remarkable,” he said. “It shows the huge strength of social norms of business as usual, and it shows that the reason we aren’t treating this as an emergency is because people still don’t think it’s an emergency, despite the clear science and despite recent catastrophic climate events.”

Salamon said she is optimistic, however, that activists could help rouse voters for the US midterm elections, or force countries such as the UK to call an end to oil and gas drilling. “I just want everyone to think about climate,” she said. “Even those who are mad at the climate activists. It’s better to be mad than to just keep ignoring them.”