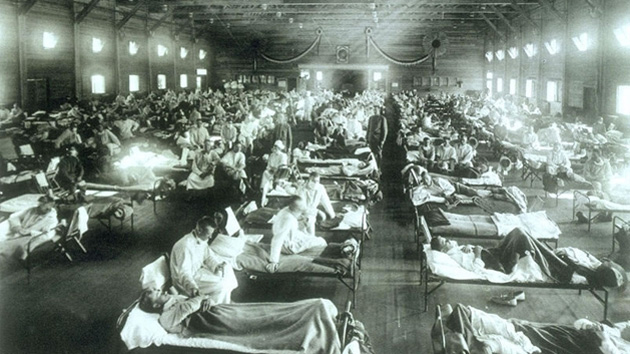

The spread of a highly infectious strain of avian influenza is killing wild birds and has prompted the culling of domesticated animals.PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo via Hakai Magazine

This story was originally published by Hakai Magazine and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Bernie sniffs the disembodied wing, picks it up in his jaws, and runs away. Four years after we adopted him, our dog’s recall is generally a point of pride. A sharp blast on a pea whistle helps when his mind drifts. But even that will fail when he’s found something disgusting or rotten. A bloated seal carcass to rub himself on. A catshark washed up in the surf. The remains of a seabird.

After 20 seconds or so, I manage to tempt Bernie away from the wing, mostly sinew with a few cream-colored feathers, probably a gull of some kind. Kittiwakes, little gulls, herring gulls: they all frequent the shores of southwest England that my family and I call home. All told, Bernie is acting like a typical dog—an opportunistic scavenger. In my head, however, this banal scene flashes into a dire vision: another pandemic.

For months, I have been following the media coverage of the devastating outbreak of avian influenza as it’s killed thousands of seabirds in Scotland. In the summer of 2022, gannets and skuas on Scotland’s remote isles started behaving oddly. They walked in circles as if intoxicated. Their heads swelled. They dragged their limp wings at their sides, feathers grazing the ground. At a time when they should have been breeding and raising new life, they were dying. Scientists and birdwatchers had a front-row seat to an ecological disaster. More than two-thirds of the world’s gannets and great skuas—birds that migrate across the Atlantic Ocean from eastern North America to western Europe—are feared to have been lost.

As the influenza tore through seabird colonies near my home, it also spread over the Atlantic into eastern Canada, through the United States, and, most recently, into South America, jumping into new hosts as it went. Eagles, pelicans, and even mammals such as red foxes, seals, and bears have died after coming into contact with infected birds.

The avian flu outbreak has killed thousands of birds. This one was spray-painted orange by scientists.

Danni Thompson/Alamy Stock Photo via Hakai Magazine

All of this is incredibly unusual. Seabirds shouldn’t die from the flu. The type of influenza virus that infects birds—known as influenza A, or bird flu—is traditionally mild; most birds don’t show any sign of sickness. Its natural habitat is within the digestive systems of seabirds and waterfowl, such as ducks and geese. It spreads through bodily fluids and fecal matter in the water. It’s a natural part of wetland and coastal ecosystems.

But this outbreak has killed thousands of seabirds. It has also survived through the summer, a season usually free from influenza in the northern hemisphere. And it jumps into mammals, an entirely new host, with aplomb. The situation has scientists wondering: Is this the new norm? And if so, should we be concerned that it will adapt to, and spread through, humans next?

There are four main types of influenza: A, B, C, and D. While all are capable of causing illness in humans, types A and B cause the majority of infections in flu season. One of the predominant strains we have vaccines for, known as H1N1, was responsible for the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic that killed more than 50 million people. Only influenza A viruses are known to cause pandemics.

The flu currently circulating through bird populations up and down Atlantic coastlines is a type of influenza A known as H5N1. That’s the virus’s short name. The only people who use its full name—H5N1-HPAI-clade 2.3.4.4b—are typically scientists who study emerging viruses, such as Nichola Hill at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Hill wishes influenza scientists had come up with a simple nomenclature, like the Greek alphabet used to name COVID-19 strains, “but we just didn’t,” she says. A pain to say aloud, which Hill does often (“… clade two point, three point, four point, four B”), this name nonetheless explains the virus’s backstory: where it originated and why it’s so deadly.

Let’s start at the end—2.3.4.4b—which is the virus’s clade. A clade is a group of organisms with a common ancestor. For example, humans are in the hominoid clade along with apes. Clade 2.3.4.4b first emerged some time around 2015 through the merger of a virus found on poultry farms and a virus that circulates in wild birds. It’s a hybrid, which is not unusual: the whole family of influenza A viruses trades and mixes its genes whenever it meets, trying out new combinations of H and N proteins (H5 with N1, or H3 with N2) just as we change our clothes.

Working backward, the next part of the virus’s name, HPAI, stands for highly pathogenic avian influenza, a form of bird flu that kills more than 75 percent of chickens in a laboratory setting in less than 10 days. That kind of lethality, Hill says, “never, ever, ever, ever [evolves] in wild birds.”

H5N1-HPAI-clade 2.3.4.4b started out as a milder influenza, a so-called low pathogenic avian influenza circulating in the wild. For its own survival, a virus shouldn’t kill its host, at least not quickly. If it were only spreading through waterfowl and seabirds, such virulence would be an evolutionary dead end. The virus would burn itself out. Only when the virus spread from domestic geese into industrialized chicken farms did it become such a killer.

Poultry farms are constantly replenished with near-identical chickens, meaning a virus can keep spreading with ever-greater ferocity. “The virus doesn’t mean to, it doesn’t want to, but that’s the pathway that allows for the virus to replicate successfully in that population,” says Hill.

Industrial poultry production has shaped the types of bird flu that surround us and increased the possibility that viruses can spill over into human populations. Most infectious diseases, author David Quammen writes in Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic, “are not simply happening to us; they represent the unintended results of things we are doing.”

Viruses multiply in their hosts’ cells and spread to new hosts when an opportunity arises. Time is crucial. Unlike previous avian influenzas, H5N1-HPAI-clade 2.3.4.4b has had more time than usual to replicate. The virus has been infecting birds throughout the summer in the northern hemisphere, a period once thought to be too hot for its survival.

Paul Digard, a virologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, wonders if the virus evolved to be more environmentally stable. “That might explain also why we’re getting so many more poultry infections, because [the virus] is just hardier,” he says. “It takes longer to die.”

Digard is digging into that possibility, but the answer may be more complex. “It could also just be chance,” he says. The virus may have infected two neighboring birds at just the right time to jump into a new type of host. “Two spinning wheels have intersected at the wrong point of the virus life cycle,” Digard says. For the virus, however, it was the right point—an opportunity.

The actors in this chance event are hard to pin down. Since 2018, this virus has been circulating widely through wild bird populations in the vast European melting pot. The virus may have made multiple incursions into seabirds. Great skuas are scavengers, and sometimes cannibalistic, and could have eaten an infected bird close to their breeding colonies in Scotland, Iceland, and Norway. Once there, the virus would have found the perfect environment in which to replicate. Dense populations, all pooping and jostling for space, shedding their viral loads to their neighbors. The fact that it was warm might have been an insignificant brake on the proceedings.

By infecting migratory seabirds at the right time and in the right place, clade 2.3.4.4b was able to make a journey no HPAI we know of has made before: crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Historically, HPAI influenzas in North America have either emerged locally or crossed the Pacific. Yet in December 2021, the virus was found in domestic birds in St. John’s in Newfoundland and Labrador, likely caught from infected seabirds that flew over through Iceland, Greenland, and the Canadian high Arctic. The latest data from the US Department of Agriculture shows the clade has since spread across the United States up to Alaska’s western coast. With flocks moving up and down the Atlantic Flyway, the invisible highway that birds use to migrate from North America to the Caribbean, Central America, and South America, the virus has already migrated far south. Late in November 2022, roughly 14,000 seabirds, including pelicans and blue-footed boobies, died along the coast of Peru. Each body was disposed of in a black bin bag.

In short, this outbreak of bird flu is unprecedented. What happens next is anyone’s guess. “It might mean that the virus is just going to become endemic [in wild birds] for a while,” says Digard. The birds that have already survived infection might harbor some innate resistance, and in time that immunity may spread. In the meantime, this highly lethal flu will be a constant threat to avifauna around the world.

The virus’s persistence and geographic spread also raise the risk of it spilling over into humans. “It’s hard to predict, but there’s no reason why it can’t happen,” Digard says.

Since April 2022, H5N1-HPAI-clade 2.3.4.4b has infected two people, one in the United Kingdom, one in the United States. Both caught the virus from domestic birds, and both were asymptomatic. But it’s a sign that this virus is at least somewhat familiar with our biology. The virus has also evolved to evade the immune systems of mammals, animals that are much more closely related to us than birds. Though rare, each such case is a step closer to spreading between humans.

“They’re all low probability events, but potentially high consequence, so you have to worry about them,” Digard says.

This strain of avian flu is capable of jumping to mammals; its spread has led to seal deaths in the Gulf of Maine.

Michael Doolittle/Alamy Stock Photo via Hakai Magazine

As ominous as this bird flu appears, there are also signs that this virus is evolving away from human transmissibility. Samantha Lycett, a molecular epidemiologist at the University of Edinburgh who studies the genetic evolution of influenza, has yet to see the sort of mutations that allow the virus to threaten our bodies.

To Lycett, H5N1-HPAI-clade 2.3.4.4b appears content in wild birds. “It’s doing quite well for itself,” she says. “You are getting these spillovers [into mammals], but is that basically because there’s just a lot of [the virus] about? I think that probably is the case.”

Short of the virus increasing its ability to leap into humans, Digard says, “I also worry that if you have lots of dead birds in the environment, then domestic cats are going to be interested, dogs are going to be interested.” Dogs like Bernie. “I really wouldn’t want to see cases of infection of pets,” he adds.

While some infectious diseases emerge from our forays into a cave or a patch of forest, avian influenza has unfurled around coastlines, easily accessible conduits to human communities. Even if this particular variant doesn’t spread through our species, our collective conscience should be heavy. Indirectly, we gave birth to this highly pathogenic menace.