Yanomami youth in Alto Alegre, July 2000. Joedson Alves/EFE/Zuma

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The surveillance plane eased off the runway and banked west towards the frontline of one of Brazil’s most dramatic environmental and humanitarian crises.

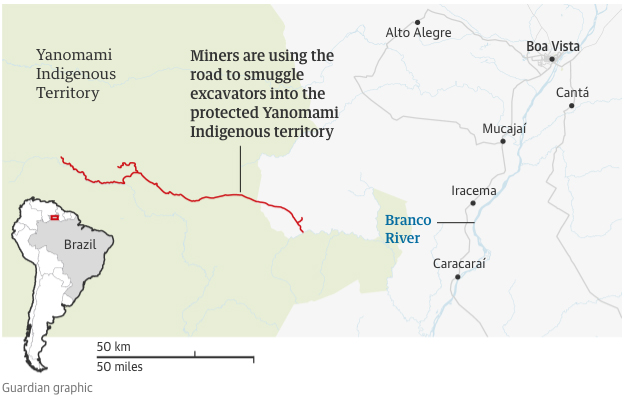

Its objective: a clandestine 75-mile road that illegal mining mafias have carved out of the jungles of Brazil’s largest Indigenous territory in recent months, in an audacious attempt to smuggle excavators into those supposedly protected lands.

“I call it the Road to Chaos,” said Danicley de Aguiar, the Greenpeace environmentalist leading the reconnaissance mission over the immense Indigenous sanctuary near the Brazilian border with Venezuela.

Illegal gold miners have carved a road through Brazil’s biggest indigenous reserve

Aguiar said such heavy machinery had never before been detected in the Yanomami territory—a Portugal-sized sweep of mountains, rivers and forests in the extreme north of Brazil’s Amazon. “We believe there are at least four excavators in there—and that takes mining in Yanomami territory to the next level, to a colossal level of destruction,” the senior forest campaigner said, as his team prepared to take to the skies to confirm the road’s existence.

The plane’s cabin filled with excited chatter an hour into the flight, as the first glimpses of the clandestine artery came into view. “We found it, people!” the navigator celebrated, while the pilot performed a series of stomach-churning manoeuvres over the canopy to get a clearer view of the dirt track.

“That’s the Road to Chaos,” Aguiar announced through the plane’s internal communication system.

“And this is the chaos,” he added, pointing to a gaping hole in the rainforest where three yellow excavators had clawed a goldmine out of the banks of the coffee-coloured Catrimani River.

In a nearby clearing, a fourth digger could be seen wrecking a territory home to about 27,000 members of the Yanomami and Ye’kwana peoples, including several communities that do not have contact with the outside world. Worryingly, one of those isolated villages is just 10 miles away from the illegal road, Aguiar said.

Sônia Guajajara, a prominent Indigenous leader who was also on the plane, suspected the criminals had benefited from Brazil’s recent presidential election to sneak their equipment deep into Yanomami lands. “Everyone was focused on other things, and they took advantage,” Guajajara said.

The arrival of excavators – witnessed for the first time by journalists from the Guardian and Brazilian broadcaster TV Globo – is the latest chapter in a half-century assault by powerful and politically connected mining gangs.

Wildcat prospectors known as garimpeiros began flocking to Yanomami land in search of tin ore and gold in the 1970s and 80s, after the military dictatorship urged poor Brazilians to occupy a region it called “a land without men for men without land”.

Huge fortunes were made – and often lost. But for the Yanomami it was a catastrophe. Lives and traditions were upended. Villages were decimated by influenza and measles epidemics. About 20% of the tribe died in just seven years, according to the rights group Survival International.

A global outcry saw tens of thousands of miners evicted in the early 1990s as part of a security operation called Selva Livre (Jungle Liberation). Under international pressure, Brazil’s then president, Fernando Collor de Mello, created a 9.6m-hectare reserve. “We have to guarantee the Yanomami a space so they don’t lose their cultural identity or their habitat,” Mello said.

Those efforts initially succeeded but by the next decade the garimpeiros were back due to soaring gold prices, lax enforcement and grinding poverty that ensured mining bosses a constant supply of exploitable workers.

The assault intensified after Jair Bolsonaro – a far-right populist who wants Indigenous lands opened to commercial development – was elected president in 2018, with the number of wildcat miners on Yanomami land reaching an estimated 25,000.

“It was a government of blood,” said Júnior Hekurari Yanomami, a Yanomami leader who blamed Bolsonaro for emboldening the invaders with his anti-Indigenous rhetoric and for crippling Brazil’s environmental and Indigenous protection agencies.

When Guardian journalist Dom Phillips, who was murdered in the Amazon last June, visited a mine in the Yanomami territory in late 2019, he found “a hand-operated industrial hell amid the wild tropical beauty”: mud-caked miners using wooden scaffolding and high-pressure hoses to blast their way through the earth.

“It’s astonishing. You’re in the lap of this great forest and it’s almost as if you’re in one those old films about ancient Egypt … All those monstrous machines destroying the earth to make money,” said the photographer João Laet who travelled there with the British reporter.

Three years later, the situation has deteriorated further with the arrival of hydraulic excavators and the illegal road.

Alisson Marugal, a federal prosecutor tasked with protecting Yanomami lands, said the introduction of such machinery was a troubling development for communities already facing an acute “humanitarian tragedy”.

Miners, some with suspected ties to drug factions, had brought sexual violence, malaria outbreaks and forced health posts to close, exposing children to “scandalous” levels of disease and malnutrition. Rivers were being poisoned with mercury by an illegal fleet of about 150 mining vessels.

Marugal said Brazil’s underfunded environmental agency Ibama launched sporadic crackdowns, blowing up and torching illegal airstrips, helicopters and planes used to reach the territory. But the intermittence of such missions – and the huge economic rewards involved – meant they were only a temporary inconvenience.

Bush pilots could receive up to 1,000,000 reais (£160,000) for a few, perilous months ferrying prospectors, supplies and sex workers to remote jungle camps. For their bosses, the profits were greater still.

Brazil’s incoming president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has pledged to put the garimpeiros out of business and slash deforestation, which has soared under Bolsonaro.

“Both Brazil and the planet need the Amazon alive,” Lula said in his first speech after narrowly defeating his rival in October’s election.

Marugal believed stopping illegal mining on Yanomami land was perfectly possible if there was political will, which was something entirely lacking under Bolsonaro. In fact, Ibama already had a plan involving a relentless, six-month offensive that would have cut off the miners’ supply lines and force them to flee the forest by starving them of fuel and food.

Aguiar argued a militarized crackdown would not succeed in the long term unless it was accompanied by policies attacking the hardship on which environmental crime was built.

“This isn’t going to be fixed just with rifles,” said the campaigner. “Overcoming poverty is an essential part of overcoming this economy of destruction.”

Hekurari Yanomami also hopes for a large-scale federal intervention when the new government takes power in January, but warns that defeating the garimpeiros will not be easy.

“These miners don’t just carry spades and axes … They have rifles and submachine guns … They are armed and all of [their] bases have heavily armed security guards with the same kind of weapons that the army, the federal police and the military police use,” he said.

The price of inaction would be obliteration for a people who have inhabited the rainforest for thousands of years.

“If nothing is done we’ll lose this Indigenous land,” Marugal said. “For the Yanomami, the outlook is grim.”