“It is a bit like being in a cathedral. It has high ceilings and when you’re standing inside the mountain, there’s hardly any sound."NordGen

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

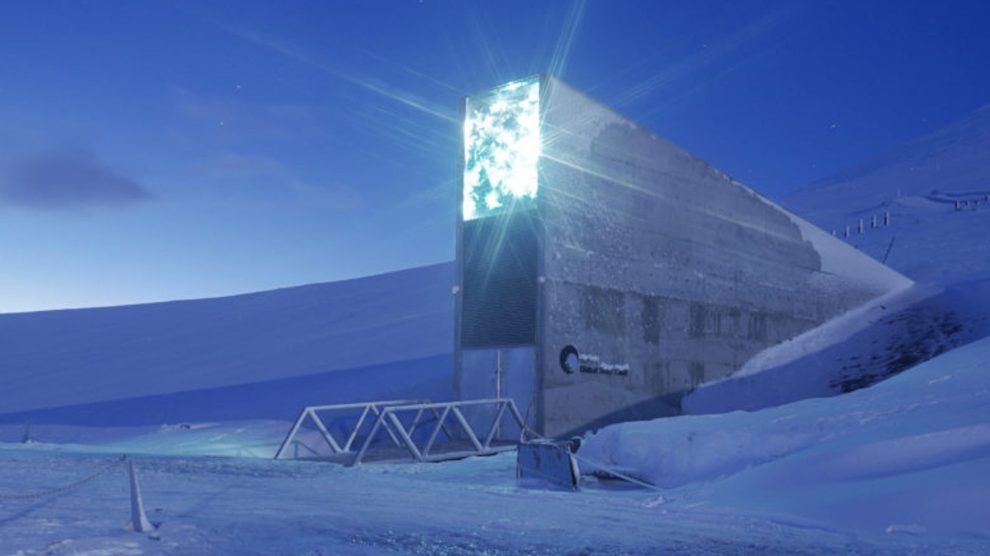

Jutting out of the permafrost on a mountainside on Spitsbergen, in the Svalbard archipelago, the entrance to the world’s “doomsday” seed vault is worthy of any James Bond movie. Surrounded by snow, ice and the occasional polar bear, the facility houses 1.2 million seed samples from every corner of the planet as an insurance policy against catastrophe. It is a monument to 12,000 years of human agriculture that aims to prevent the permanent loss of crop species after war, natural disaster or pandemic.

The Global Seed Vault in the Norwegian Arctic, which opened in 2008, is closed to the public and shrouded in mystery, the subject of numerous internet doomsday conspiracy theories. Now, to celebrate the vault’s 15th anniversary, everyone is invited on a virtual tour to see inside the vast collection of tubers, rice, grains, and other seeds buried deep in the mountain behind five sets of metal doors.

The deep-freeze, designed to last forever, is co-managed by the Norwegian government, the Crop Trust and NordGen, the genebank of the Nordic countries. The seeds could hold answers to agricultural challenges posed by climate crisis, invasive species, pests, changes in rainfall patterns and rampant biodiversity loss are studied, and it opens three times a year to accept new deposits from other seed banks around the world. Scientists say they hope people will learn more about their work through the virtual tour—without running the risk of falling prey to a polar bear.

“It is a bit like being in a cathedral. It has high ceilings and when you’re standing inside the mountain, there’s hardly any sound. All you can hear is yourself,” says Lise Lykke Steffensen, executive director of NordGen, which is responsible for the day-to-day operation of the vault. “When you open the door [to the collections], it’s -18C—the international standard for conserving seeds—which is very, very cold. Then you see all of the boxes with seeds from all of these countries. I’ve been so many times and I’m still curious.”

After the Aleppo seed bank was destroyed in the Syrian civil war, the vault was used to replenish seeds for the first time by the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, a regional hub based in Aleppo to study crops from the cradle of civilization where agriculture first began. Research into the resilience of these crops and plant species could be vital as the planet heats in the coming decades.

It may look like an ordinary warehouse, but it’s actually “one of the most important global public goods we have on Earth.”

NordGen

Away from the panoramic view of the Arctic night from the vault’s entrance, the virtual tour takes you down a long tunnel deep into the mountain. Eventually, you arrive at the “cathedral,” home to the three seed chambers, each of which can store nearly 3,000 seed boxes. Each species is sealed in an aluminum airtight bag and kept in its country’s box. As you make your way between what look like the shelves of a DIY warehouse, you can click on a country’s box to find out more.

In theory, the seeds are safe, although the entrance to the facility flooded with meltwater in 2017 after a heatwave in Svalbard. The island is the most rapidly warming part of the planet but experts say the deposits are buried so deep in the permafrost that they will be safe for centuries. Seeds are replaced every few decades and if the cooling system ever failed, it would probably take hundreds of years for the temperature inside the vaults to rise above zero.

“The virtual tour gives everybody the opportunity to look inside. We think that is a general question of transparency and accountability to the broader public,” says Stefan Schmitz, executive director of the Crop Trust. “What is secured inside the vault is one of the most important global public goods we have on Earth. But we need to protect them, secure them and to make sure that they are conserved in perpetuity.”

This week, the vault welcomed first-time deposits from Albania, Croatia, North Macedonia and Benin, alongside wild strawberry varieties from a German research institute. Plants such as these could be key to helping humanity feed growing populations in a warmer world, says Schmitz.

“These wild strawberries are amazing. They have proved simply by their ability to survive in nature for millions of years that they are robust,” says Schmitz. “They can withstand changes in climate, they can withstand harsh situations with hardly any soil and that is exactly what plant scientists and breeders are interested in. Today, we can start breeding from varieties that are resilient to harsher climates.”