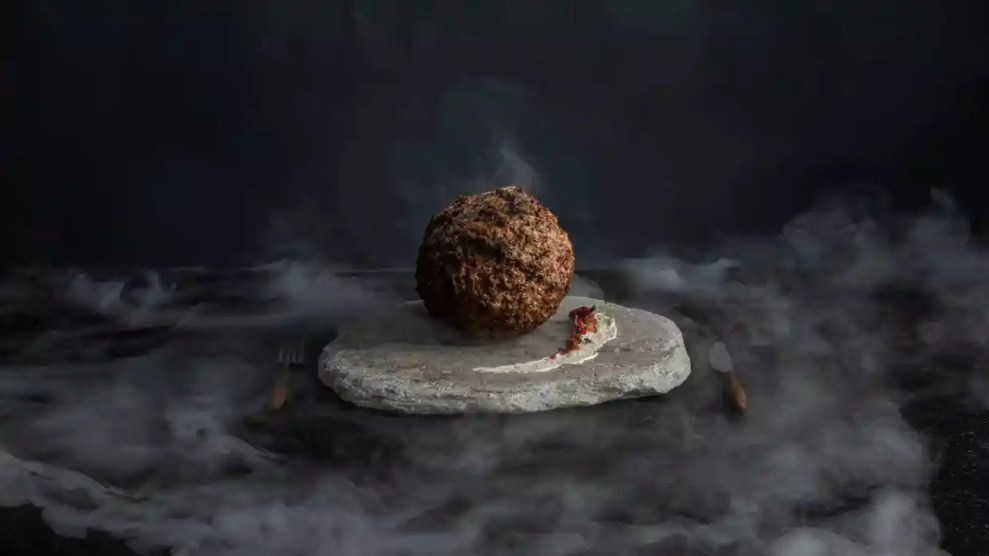

Vow created the mammoth meatball to demonstrate the potential of meat grown from cells, without the slaughter of animals.Aico Lind

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A mammoth meatball has been created by a cultivated meat company, resurrecting the flesh of the long-extinct animals.

The project aims to demonstrate the potential of meat grown from cells, without the slaughter of animals, and to highlight the link between large-scale livestock production and the destruction of wildlife and the climate crisis.

The mammoth meatball was produced by Vow, an Australian company, which is taking a different approach to cultured meat.

There are scores of companies working on replacements for conventional meat, such as chicken, pork and beef. But Vow is aiming to mix and match cells from unconventional species to create new kinds of meat.

The company has already investigated the potential of more than 50 species, including alpaca, buffalo, crocodile, kangaroo, peacocks and different types of fish. The first cultivated meat to be sold to diners will be Japanese quail, which the company expects will be in restaurants in Singapore this year.

“We have a behavior change problem when it comes to meat consumption,” said George Peppou, CEO of Vow. “The goal is to transition a few billion meat eaters away from eating [conventional] animal protein to eating things that can be produced in electrified systems.”

“And we believe the best way to do that is to invent meat. We look for cells that are easy to grow, really tasty and nutritious, and then mix and match those cells to create really tasty meat.”

Tim Noakesmith, who cofounded Vow with Peppou, said: “We chose the woolly mammoth because it’s a symbol of diversity loss and a symbol of climate change.” The creature is thought to have been driven to extinction by hunting by humans and the warming of the world after the last ice age.

The initial idea was from Bas Korsten at creative agency Wunderman Thompson: “Our aim is to start a conversation about how we eat, and what the future alternatives can look and taste like. Cultured meat is meat, but not as we know it.”

Plant-based alternatives to meat are now common but cultured meat replicates the taste of conventional meat. Cultivated meat—chicken from Good Meat—is currently only sold to consumers in Singapore, but two companies have now passed an approval process in the US.

In 2018, another company used DNA from an extinct animal to create gummy bears made from gelatine from a mastodon, another elephant-like animal.

Vow worked with Prof Ernst Wolvetang, at the Australian Institute for Bioengineering at the University of Queensland, to create the mammoth muscle protein. His team took the DNA sequence for mammoth myoglobin, a key muscle protein in giving meat its flavor, and filled in the few gaps using elephant DNA.

This sequence was placed in myoblast stem cells from a sheep, which replicated to grow to the 20 billion cells subsequently used by the company to grow the mammoth meat. “It was ridiculously easy and fast,” said Wolvetang. “We did this in a couple of weeks.” Initially, the idea was to produce dodo meat, he said, but the DNA sequences needed do not exist.

No one has yet tasted the mammoth meatball. “We haven’t seen this protein for thousands of years,” said Wolvetang. “So we have no idea how our immune system would react when we eat it. But if we did it again, we could certainly do it in a way that would make it more palatable to regulatory bodies.”

Wolvetang said he could understand people initially being wary of such meat: “It’s a little bit strange and new—it’s always like that at first. But from an environmental and ethical point of view, I personally think [cultivated meat] makes a lot of sense.”

The large-scale production of meat, particularly beef, causes huge damage to the environment, with many studies finding there must be a big reduction in meat-eating in rich nations in order to end the climate crisis.

Cultivated meat uses much less land and water than livestock, and produces no methane emissions. Vow said the energy it uses is all from renewable sources and that fetal bovine serum, a growth medium produced from cattle fetuses, is not used in any of its commercial products. The company has raised $56 million in investment to date.

Wolvetang thinks there will be increasing crossover between the technologies used in medical and human stem cell research and the production of cultured meats. For example, cells can be programmed to develop in response to their immediate environment, meaning cuts of meat containing muscle, fat, and connective tissue could be grown.

Seren Kell, at the Good Food Institute Europe, said: “I hope this fascinating project will open up new conversations about cultivated meat’s extraordinary potential to produce more sustainable food.”

“However, as the most common sources of meat are farm animals such as cattle, pigs, and poultry, most of the sustainable protein sector is focused on realistically replicating meat from these species,” Kell said. “By cultivating beef, pork, chicken and seafood we can have the most impact in terms of reducing emissions from conventional animal agriculture.”

The mammoth meatball will be unveiled on Tuesday evening at Nemo, a science museum in the Netherlands.