Gavin Schneider is trying to create a protein made from mycelium—the so-called "body" of fungi—that could help replace meat. Marc Fawcett-Atkinson/National Observer

This story was originally published by Canada’s National Observer and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In an anodyne gray North Vancouver business park, Gavin Schneider is growing a whitish paste he believes will one day replace meat and feed astronauts on Mars.

The paste is mycelium, the so-called “body” of fungi. This long-overlooked organism has recently burst into the spotlight, with proponents saying it offers remedies to some of the ills of industrialization, like plastic pollution. The Canadian Space Agency has even shown interest in Schneider’s work as a possible source of food for space missions.

“I think there is really going to be a niche of application,” said UC Davis professor Valeria La Saponara, an aerospace engineer who started working with mycelium several years ago.

A network of thread-like strands, mycelium can digest organic matter and some chemicals and be formed into different shapes and textures. That makes it ideal to create things like compostable plastics, “living” building materials that can repair themselves and techniques to clean soils of chemicals—but “it cannot replace everything,” she said.

And if Schneider is right, it could be the newest trend in alternative meats.

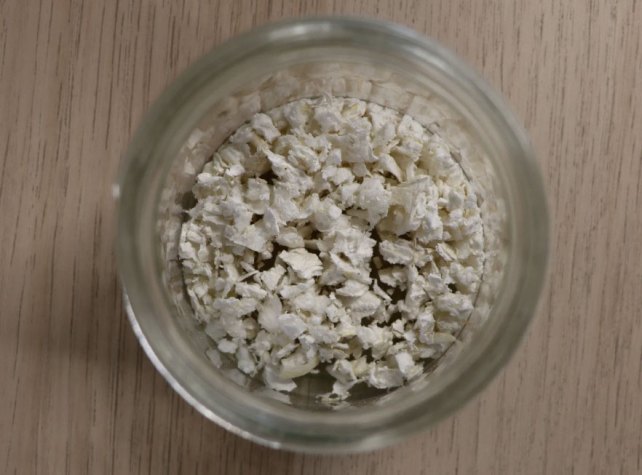

“It’s a fibrous, high-protein ingredient that will be used in meat analogs,” he explained, showing off a handful of the popcorn-like flakes his company, Maia Farms, made by drying the whitish paste. Once compressed, flavored and colored, the flakes can “become anything you want,” from imitation burgers to plant-based steak.

The mycelium flakes can be pressed into imitations of most common cuts of meat, Schneider says.

Marc Fawcett-Atkinson/National Observer

For commercial production, the mycelium can be grown inside large steel vats, similar to the ones used by microbreweries, that are filled with a liquid made from the residue of crops like canola, potatoes or barley. The organism feeds off this soup, producing a mat of mycelium—it resembles the so-called “mother” in kombucha—that can be harvested after a few days of growth.

Once the company scales up its production enough to start selling, Schneider estimates Maia Farms will be pumping out enough each week to equal the weight of roughly 700 cattle. With growing demand for protein and strong evidence we need to reduce meat production to address climate change, he believes “mycoprotein…will be a staple food source in 20 years.”

For anyone who follows the world of food, that might sound like a familiar pitch. Starting in the 2010s, dozens of alternative meat startups promised they were the key to drastically reducing meat consumption.

More people were growing concerned about the environmental and ethical impacts of animal agriculture—particularly factory farming—fueling widespread speculation that plant-based meats could be key to edging out the real thing. On the back of this hype, startups like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods shot onto fast-food chain menus and legacy meat processors like Maple Leaf Foods started investing heavily in the industry.

Recent months have tempered those expectations, with analysts now predicting more modest growth in the sector. Still, some observers say this more sombre outlook shouldn’t hit mycelium “meat” too hard.

Mycelium “is much cheaper to make. You don’t have to conduct so much processing. It’s more natural” than existing plant-based commercial meat alternatives, said Sylvain Charlebois, a professor at Dalhousie University who studies the food industry. Most common alternative meats rely on heavy processing to transform soy or pea protein into a stimuli-meat. That has made them expensive and less appealing to consumers, he said.

“Investors are looking at the product itself. Not the mystique, but the product itself—the ingredients, the taste,” he explained. “It’s all about cutting costs, making the product more natural with less sodium. That’s basically what the entire industry is aiming for.”