Kherson, Ukraine in the aftermath of the Kakhovka dam breach.Maxym Marusenko/AP

This story was originally published by Slate and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

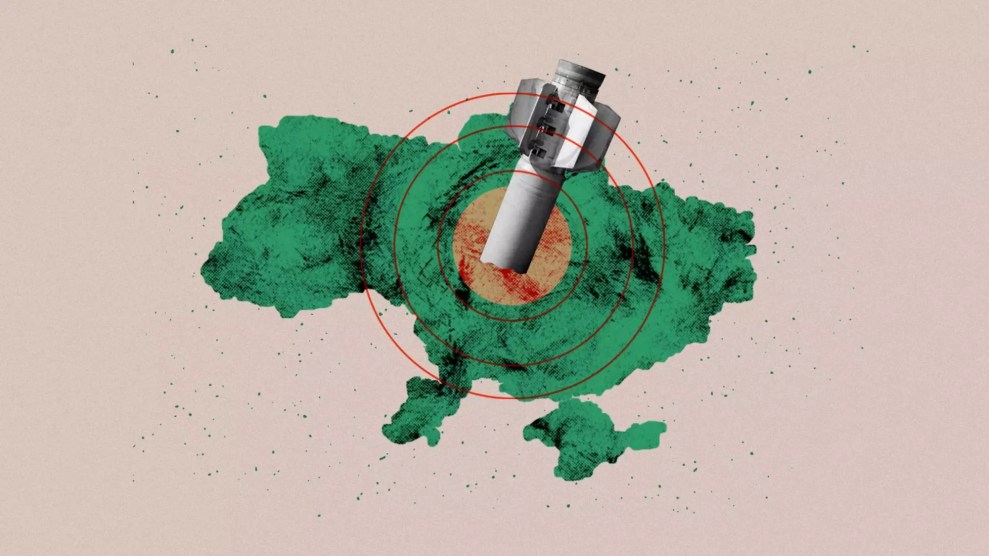

As the Russia-Ukraine War rages on, its most devastating impacts are adding up and extending far beyond Eastern Europe. Last week offered an extremely grim example: The Kakhovka Dam, perched on the Dnieper River in Kherson province, was blown up on June 6, draining the Kakhovka’s reservoir into the river and over its banks. Surrounding lands, homes, and infrastructure were deluged with poisonous runoff, forcing thousands of residents to flee.

While we still don’t know who is responsible for the demolition—each side has the blamed the other—Russia and Ukraine have both suffered serious damage; both nations claim different regions within Kherson province, and Kakhovka lies under Russian control. The dam’s destruction also doesn’t provide a clear advantage to either side in the conflict: The military front lines have devolved into muck, and the livelihoods of both Russians and Ukrainians are at risk. Really, the attack—which one former Ukrainian minister of ecology claimed might be the country’s “worst ecological disaster since Chernobyl”—won’t affect the war as much as it will hurt both countries for years to come, and the rest of the world with them.

It’s already bad. As water drained from the dam and flooded a 50-mile stretch of the Dnieper, Ukrainian territory along the western banks was swallowed up wholesale—farms, gas stations, land mines, armories, factories, houses, railroad tracks, forests. As the Dnieper River rose to dangerous heights, residents and government officials reported sickening sights across Kherson province. The floodwaters bore “pesticides, chemicals, oil, dead animals and fish,” and even detritus from graveyards, one Ukrainian told the New York Times; President Volodymyr Zelensky informed environmental activists that the runoff bore “sewage, oil, chemicals,” and maybe even toxic materials from “at least two anthrax burial places” located in the region. In a national zoo within the southern Ukrainian city of Nova Kakhovka, which is under Russian control, thousands of animals drowned. About 14 human deaths have been recorded, with dozens more missing and up to 100,000 at risk of displacement.

Unlike its opponent, the climate-minded Ukrainian government has brought ample attention to Kakhovka’s environmental and energy implications over the past week. The country’s officials have pointed out that the dam—one of the world’s largest—once served as both a major hydropower generator and a source of cooling water for the upstream Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant. The explosion won’t have a near-term effect on electricity supply; both the hydro and nuclear facilities were overtaken by Russian forces in the early stages of the 2022 invasion, and subsequently decoupled from Ukraine’s grid.

The far bigger concern, then, is with Kakhovka’s water discharges. Its reservoir, which is draining up to four cubic feet of water each day, is already at only a quarter of its pre-blast capacity. Concerns abound that as Zaporizhzhia draws from its water reserves to cool itself over the coming months, it may eventually run out of backup sources of water as well as skilled human laborers—which would cause a nightmarish meltdown in the area.

There’s also the matter of the debris the Kakhovka’s water has splashed across Eastern Europe—and the runoff that will inevitably flow to the Dnieper’s entrypoint into the Black Sea. Zelensky announced last week that because Kakhovka’s hydroelectricity turbines are now underwater, about 150 tons of the machine oils used for the plant’s engines have been washed away, polluting the floodwaters even before they traveled across Kherson. (There are 300 more tons of lubricants remaining in the plant that could yet be spilled, which would be horrific for the wildlife in the Black Sea, now rapidly transforming into a “garbage dump and animal cemetery” in the Ukraine government’s words.)

These waters have drenched more than 125,000 acres of forest, Zelensky said, and tens of thousands of birds and other animals may die as a result. His government’s Agriculture Ministry further noted that 25,000 acres of Ukrainian-controlled farmland were crushed by the water, and that Russia-occupied agricultural plains suffered even more; crops and livestock from both sides have been swept away from their homes. Freshwater fish that depended on the Kakhovka reservoir have washed away as well, and it’s likely they’ll die once they hit the saltwater-heavy Black Sea.

At this point, little in Ukraine has been spared: not the national parks, not the shellfish or aquatic plants, not the planting soil that’s being salinated by the floods, not the endangered mammals that depend on the Dnieper. The Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group warns that the fallow lands left behind from the disaster may soon be overrun with invasive species.

Such massive losses of habitat, vegetation, and farmland portend an even bleaker future for Ukrainians. Already, tens of thousands of them lack drinking water that the Kakhovka’s reservoir provided to them (that is, if their villages haven’t completely flooded as is), and Russia-controlled Crimea will also feel the tap shutoffs. For the farmers whose plots were spared, their worry now turns to much-needed irrigation.

Ukraine’s Agriculture Ministry estimates that about 1.2 million farming acres will have to cease production, and that the reservoir will need to be rewilded in order to prevent it from turning into poisonous dust (this being the result of the farming pesticides that ran off from croplands to collect at the very bottom of the reservoir). This could halt the growth of up to $1.5 billion worth of grain and oil seeds, the ministry added.

This gets into another emergency: what Ukraine’s industrial and agricultural damage portends for the rest of the world. The Black Sea, already Europe’s most polluted water body, is a region of high importance to its other coastal neighbors: Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, and Georgia. They’ve all played their own roles in muddying those waters, but they all also depend on the Black Sea for tourism, for trade and travel, for industrial and energy development. Accelerated pollution of the sea will harm each of those nations.

Furthermore, there’s cause for alarm over Ukraine’s specific exports, industries, and food supplies. If Ukraine’s Agricultural Ministry is correct in estimating that the Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Dnipro regions will be hardest hit by the destruction of the dam burst, then Ukraine’s trade partners should pay close attention—especially since so much of Ukraine’s farming goes to export. As the Wall Street Journal notes, the three aforementioned areas make for 12 percent of the country’s agricultural output, especially in vegetables and barley. To look at Kherson specifically, one only has to point out that several grain-storage siloes were destroyed in the explosion’s aftermath, while food-processing giants AgroFusion and Chumak own several factories and acres in the province.

Beyond the plundered commodities, which many poor countries rely on, there are still other industries at stake, and questions as to whether Ukraine will be able to trade much at all near-term. The country’s largest steel producer has halted operations for the time being in order to reduce water demand. A key ammonia pipeline was also broken alongside the Kakhovka dam, which will sap Ukraine’s fertilizer and grain exports. And numerous trading ports on the Dnieper River that helped transport products like crops and construction material “have been rendered unusable by the draining of the reservoir,” as the head of Ukraine’s Shipping Administration told the New York Times.

All of this will take years to repair, and some of it may not ever be fixed. Farmland turned brittle from lack of water and sediment deposits may never recover the rich yields that formerly blessed Ukraine’s economy. The animal and plant species impacted will take years to repopulate—if the most endangered among them don’t go extinct. The cities and villages that relied on the Kakhovka dam and the Dnieper River, many of which were evacuated, will not rebuild for a while yet. And we have no idea how long the war will continue, and how much more of Ukraine’s fertile lands, natural resources, and waters will be afflicted as a result. The dam collapse isn’t just a Russia-Ukraine disaster—it’s a global one.