The hall of historic Waiola Church in Lahaina and nearby Lahaina Hongwanji Mission are engulfed in flames along Wainee Street on Tuesday, Aug. 8, 2023, in Lahaina, Hawaii.Matthew Thayer/AP

Fires have been raging across Hawaii’s Maui Island since Tuesday night. It is already the second deadliest wildfire in United States history, with 270 structures and 2,000 acres burned, 55 people dead, and 11,000 people without power. More than 11,000 people were evacuated on Wednesday, says Hawaii Department of Transportation director Ed Sniffen. The population of Maui is 164,000.

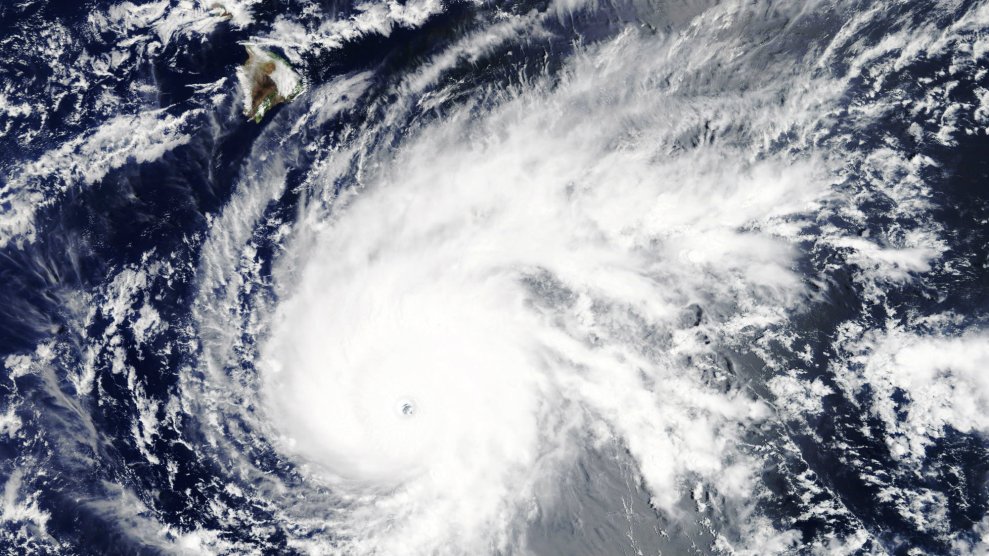

The fires are especially horrifying because Hawaii is not a natural fire ecosystem and has not evolved to rebound after wildfires. Not surprisingly, preliminary reports suggest climate change is partly to blame, since the intense winds of Hurricane Dora traveled hundreds of miles to reach the island. Erica Fleishman, director of the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute at Oregon State University, explains that “there’s an increasing trend in the intensity of hurricanes worldwide, in part because warm air holds more water.”

And there’s another culprit: The widespread, nonnative grasses that have taken over certain parts of the island.

These invasive species, like guinea grass, were introduced to Hawaii by 19th century settlers who forcibly shifted the land away from indigenous resource management practices and towards large-scale agriculture, such as cattle ranching and plantations like the Dole Pineapple Company. “The historic changes to the plants and the vegetation is really what’s making us vulnerable and susceptible to an event like this,” Clay Trauernicht, a specialist in wildland fire science and management at the University of Hawaii, Manoa, told the San Francisco Chronicle.

The plantations were then abandoned, allowing the non-native grass to spread from their bounds. Trauernicht tweeted: “The fire problem is mostly attributable to the vast extents of nonnative grasslands left unmanaged by large landowners as we’ve entered a ‘post-plantation era’ starting around the 1990s.” The number of wildfires Hawaii experienced rose drastically in the same era.

A 2021 study in the journal Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics similarly concludes that large-scale monocropping “led to the rapid loss and degradation of native ecosystems through increasing dominance by non-native plants,” and that these plants have contributed to the frequency and strength of fires. Plants native to Hawaii, on the other hand, have been shown to be beneficial in limiting wildfires.

Kaniela Ing, a former Hawaiian legislator and current director of the Green New Deal Network, tweeted that “the gross mismanagement of land by greedy developers and land speculators destroyed our natural landscape and buffers and enabled the rapid spread of the fire.”

The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)‘s sixth and latest report explains that colonialism has exasperated climate change. The report says thatcolonized areas are more likely to face worse climate disasters and linked to studies that show direct connections between environmental damage and robbing Indigenous communities of their land. Others have argued that colonialism is the direct cause of climate change, citing a fundamental societal value that motivated both colonial action and environmental degradation. “Instead of treating the Earth like a precious entity that gives us life, Western colonial legacies operate within a paradigm that assumes they can extract its natural resources as much as they want, and the Earth will regenerate itself,” said Hadeel Assali, a lecturer and postdoctoral scholar at the Columbia’s Center for Science and Society.

The fires are particularly tragic because this colonial background continues the history of harm against the Kānaka Maoli, the native Hawaiian people. The fires have wiped out Lahaina, which was once the capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom, an important cultural and historical epicenter. “Our ancestors, especially Native Hawaiians fought them every step of the way. [It] is also a reminder of that history of resistance,” Ing told NBC news on August 9th.

He also tweeted a reminder that Lahaiana isn’t just a place of history, “King Kamehameha’s palace is here. Kānaka Maoli still live here, on their ancestral land from the 1800s.”