How do you find an elusive animal that most people have never even seen dead in a fish market? Matthew McDavitt, above, knows how.Melody Robbins

This story was originally published by Hakai Magazine and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Peter Kyne sits down at his desk to write a eulogy for a fish he’s never met. It’s summer 2019. No scientist has seen signs of the critically endangered Rhynchobatus cooki, or clown wedgefish, since a dead one turned up at a fish market in 1996. Kyne, a conservation biologist at Charles Darwin University in Australia who studies wedgefish, has worked only with preserved specimens of the spotted sea creature. “This thing’s dust,” Kyne thinks, feeling defeated as he writes the somber news in a draft assessment of the global conservation status of wedgefish species for the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Wedgefish are a type of ray. They look like sharks that swam head first into a panini press, with flat faces and sharkish tails. The clown wedgefish is the runt of the 11 known species, about as long as a baseball bat. Along with their cousins, sawfish and guitarfish, wedgefish are among the most endangered animals in the sea, thanks largely to fishers who supply the shark fin trade. Fetching up to $1,000 per kilo, wedgefish’s spiny fin meat is some of the most highly sought in this ecocidal economy because it’s perfect for shark fin soup, a delicacy favored by wealthy East Asian seafood connoisseurs.

Wedgefish’s pointy snouts are easily snagged in fishing nets, so they’re also a frequent, unintended casualty of commercial fisheries. This double whammy has led to the near eradication of wedgefish worldwide. Nine species are critically endangered. Kyne is about to add an extinction to that list.

Conservation biologist Peter Kyne.

Courtesy Charles Darwin University

Just hours before submitting the final assessment, though, Kyne learns that a dead clown wedgefish has just shown up at a Singapore fish market. Relieved, he and his colleagues revise their work. But the swift action necessary to help the species won’t be possible without more information. The scientists don’t even know the critter’s habitat requirements. Somehow, they must find out where the last holdouts live.

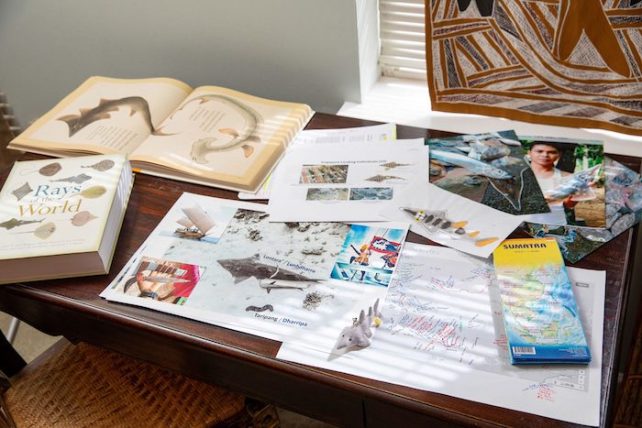

Kyne mentions the problem in a Zoom meeting about wedgefish conservation. Luckily for Kyne, his friend Matthew McDavitt is among the attendees. McDavitt is an amateur academic well versed in an emerging research methodology that turns the virtual sea of social media posts into information scientists can use to track the world’s rarest species. His curiosity ignited, McDavitt gets to work. Kyne doesn’t know it yet, but the hunt for the clown wedgefish is on.

Matthew McDavitt happens to be an expert on wedgefish and their relatives, but he’s no scientist. He grew obsessed with sawfish as a kid, when the ray’s long, toothy snout hooked his curiosity. At university, McDavitt studied archaeology and became fascinated with ancient cultural ties to sawfish when he learned the Aztecs buried sawfish snouts under their temples and rendered the fish’s likeness in paintings.

After graduating, he wanted to study the sawfish’s importance to other cultures around the world. But sawfish-adjacent ethnozoologist jobs weren’t exactly falling from the sky, so McDavitt pivoted to a legal career. He earned his law degree and became a research attorney, ghostwriting trial briefs and law articles for other attorneys, judges, and mediators, but he never gave up his passion. He started obsessing over guitarfish and wedgefish, too, cramming his marine studies into what little free time he had, sometimes unable to touch them for months. “I do it on breaks. I put in the time when I can,” he says. “I do it on weekends sometimes.”

As a student of archaeology, McDavitt grew enamored with the cultural ties of ancient civilizations to sawfish. His enthusiasm later extended to guitarfish and wedgefish.

Melody Robbins/Hakai Magazine

In the early 2000s, as the internet gained traction and social media began its rise, McDavitt mined a treasure trove of information about wedgefish and sawfish—fishing-trip photos, sightings, ancient art, whatever he could find. Over two decades, he compiled thousands of pictures and posts about various species and stored them on his computer.

At first, McDavitt served only his own curiosity about different cultures’ connections to his favorite fish. But along the way, as he contacted ecologists who studied sharks and rays to ask questions and share his findings, he discovered species in locations where they hadn’t been formally recorded before. In some cases, he found what his new ecologist friends suspected were entirely new species. “I’ll often get into work and there, in my inbox, there’s something else he’s found,” says Kyne, who met McDavitt at a sawfish conservation workshop. “I’m like, Matt, how do you do this?” McDavitt began to realize his ethnozoological research could be used to study and protect imperiled marine animals.

McDavitt was practicing what is now known as iEcology, which relies on online public data sources to study the natural world. Scientists can download thousands of records of the species they’re studying without setting foot in the field. “It’s a huge amount of data,” says Ivan Jarić, a professor at Université Paris-Saclay in France and one of iEcology’s most devout advocates. “It is, in many cases, freely available, so it’s easy and cheap to obtain it.”

Many social media posts come tagged with dates and locations, allowing scientists to track animals through space and time to study movement patterns, interspecies behavior, and the abundance and spread of invasive or endangered species. One study used pictures and videos from Italian tourists to track blue sharks along the Mediterranean coast over a decade. Another used Facebook and Instagram posts to count whales on their annual migrations along the coast of Portugal. Scientists in Hawai‘i have used tourist photos to monitor critically endangered Hawaiian monk seal populations.

The pandemic stymied field studies, but scientists took advantage of internet platforms where they could find pictures of wedgefish.

Melody Robbinsl/Hakai Magazine

iEcology’s origins trace back to at least 2011, but the method began to gain traction in the past several years, as Jarić and other scientists proselytized its advantages. It got another boost in 2020, when the pandemic scuttled fieldwork for many scientists, as iEcology offered them a remote way to continue their research. “It basically saved two years of my career,” says Valerio Sbragaglia, a behavioral ecologist at the Spanish National Research Council’s Institute of Marine Science, who spent the COVID-19 lockdown using amateur angler videos to monitor the spread of an invasive grouper species as it pushed north through a warming Mediterranean Sea.

There are other advantages, too. Field studies can be a constant game of catch-up, where data may become outdated before ecologists can publish their analyses. But iEcology allows them to monitor animals in near real time. These tools also make ecological surveys more accessible to scientists who can’t secure funding for expensive field trips. In Brazil, for instance, researchers used YouTube videos to find examples of people releasing pet fish into wild waterways, where they multiplied and became invasive. “For a developing country,” Sbragaglia says, “it’s a first source of information that can support future research.”

McDavitt’s iEcology skills have earned him a reputation among marine ecologists as a sort of super citizen scientist. His research has been cited in scientific papers detailing the illegal shark fin trade, and he has published his own research on the importance of sawfish to Indigenous peoples in Australia. McDavitt’s work was cited numerous times in a 2007 proposal that convinced the governing body behind the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, or CITES, to restrict the trade of seven species of endangered sawfish. “I’m good at finding weird things,” he says.

McDavitt begins his search for the clown wedgefish shortly after his 2019 Zoom meeting with Kyne. The first thing he does is create a methodology for sifting through social media posts. The known clown wedgefish sightings are all at fish markets in either Jakarta or Singapore. McDavitt figures the creatures must live somewhere between the two places, a vast stretch of sea dotted with thousands of islands, occupied by millions of people.

With this in mind, McDavitt compiles a list of about 25 common names for wedgefish from the local Indonesian, Chinese, and Malay dialects spoken across the western Indonesian archipelago. He targets the islands lining the coasts of Sumatra and Borneo, sometimes narrowing his queries to individual towns and villages he finds on Google Maps. His searches produce thousands of posts, many by local subsistence fishers showing off their catches. Dozens include wedgefish, but they’re all the wrong species. “I’m just going through picture after picture after picture, and most of it is, of course, not useful to me,” McDavitt says.

Hours of pouring over data gleaned from the internet eventually revealed the location of clown wedgefish, somewhere between Sumatra, Singapore, and Borneo.

Melody Robbins

In August, several weeks after Kyne almost wrote off the clown wedgefish, McDavitt hunches over a desk buried in teetering piles of legal paperwork, scrolling through Facebook posts. He pauses on yet another wedgefish photo. “It looked weird,” McDavitt says. The picture, from a 2015 post, shows a somber young Indonesian man hefting a small, flat fish. The white-edged fins and playful polka dots are unmistakable. McDavitt has found the clown wedgefish.

He jumps up from his desk and shouts for his wife. Then he emails Kyne, who has no idea what his friend has been up to until he receives the message. “If it was in the morning, I would’ve had coffee. If it was late at night, I would’ve had red wine. In either case, I probably did spit some out,” Kyne remembers.

The photo comes from Lingga Island, part of a cluster of islands wedged between Sumatra, Singapore, and Borneo. Kyne hurries to apply for grants to fund a full field study of the area. McDavitt keeps combing the web. Over the next few months, he finds five more photos of clown wedgefish from local fishers; some pictures are only a few weeks old. He and Kyne map their findings, establishing for the first time in Western science the clown wedgefish’s range, and publish their work in 2020.

Kyne also taps Charles Darwin University PhD candidate Benaya Meitasari Simeon, who’s spent years researching other wedgefish species, to spearhead the study’s local initiatives. Simeon grew up eating wedgefish, a traditional Indonesian food. Now she’s vowed to protect them; she even sports a wedgefish tattoo on one arm. Simeon musters a team of students and locals to hang illustrated wedgefish guides—scientific wanted posters—in areas where the fish has shown up on Facebook, to help local fishers identify clown wedgefish in their catch and report sightings.

Images of the clown wedgefish are about as scarce as the fish itself. Two animals on the left are clown wedgefish, and three on the right are broadnose wedgefish.

Courtesy Matthew McDavitt

A big part of Simeon’s job is convincing locals to participate in the project. Some are wary of conservationists because they fear new fishing restrictions could harm their livelihoods. The key, Simeon says, is explaining to fishers that “if it’s gone, it’s gone forever and your kids cannot see it anymore.” Her efforts pay off: Her network reports around 10 clown wedgefish catches. All are dead.

In early 2023, Simeon travels from her home in Jakarta to a Sumatran hotel room where her colleagues have a juvenile clown wedgefish for her to inspect. She takes the palm-sized spotted carcass into the hotel bathroom for a closer look. She cries as she touches it. “I saw hope,” she says.

As popular platforms like Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and Instagram become major sources of research material, scientists must grapple with new challenges. Even experts can misidentify species in amateur photos when they can’t measure, touch, or see the creature for themselves. Researchers must meticulously review and confirm the records they’ve gathered to avoid false identifications. Some have been less thorough than others.

Last year, a group of European scientists published a paper claiming to have found the first record of a young goblin shark in the Mediterranean, a deep-sea species with a face straight out of a Ridley Scott sci-fi flick. They based their conclusion on a photo taken on a Mediterranean beach. But some experts noticed that the juvenile “shark” appeared to be missing a gill and was strangely rigid for a dead fish. McDavitt spotted the fraud immediately. The proof was on his living room shelf: a plastic goblin shark toy that matched the supposed animal in the picture. The authors retracted their paper after McDavitt and others raised concerns.

Scientists using social media data to study species that have been nearly eradicated by poaching run the risk of exposing those animals to further harm. “If it’s a very rare species, you don’t want to publicize the location where the species can be found because of potential misuse,” Jarić says. And the research raises a familiar ethical conundrum. In a social media–saturated world where personal privacy is itself endangered, how do you ethically scrape pictures and videos provided by the masses without their consent? For now, scientists manage this by anonymizing posts, blurring profile photos, and removing usernames.

The McDavitts of the world need months to compile data, searching for an animal rarely photographed. One day, artificial intelligence may make the job simpler.

Melody Robbins/Hakai Magazine

And there is always the prospect of misinformation and falsehoods making it into data sets. Artificial intelligence may prove a complicated partner in this regard. Researchers like Sbragaglia have recruited coders to develop machine-learning models for disseminating massive arrays of data about a specific species. They hope these AI models will pull, in a matter of hours, databases of pictures and videos that the McDavitts of the world would need months to compile. But with the alarming advance of artificially generated images, AI could also hinder scientists’ ability to tell real pictures from fake ones. “This is terrifying,” Sbragaglia says. “But I think for the moment, it’s far away.”

On a windy day in June 2023, Kyne dives into the turquoise waters off the coast of Singkep Island, just south of the location where McDavitt discovered the first clown wedgefish post in 2019. Jungle-clad mountains loom in the distance. Palm trees lean drunkenly over white sand beaches. Simeon and other scientists watch from the boat as Kyne disappears into the depths, clutching an empty one-liter bottle. Fleets of commercial fishing boats dot the surrounding sea, underscoring the urgency of the task.

Kyne and Simeon are here to collect samples for an eDNA study, supported by three years of funding that the Save Our Seas Foundation supplied for the wedgefish search, thanks in large part to McDavitt’s findings. When a creature swims through the water, it sheds genetic material that can reveal its presence once water samples taken from that area are analyzed. When the survey results are back in six months to a year, the scientists hope they can zero in on where clown wedgefish are hiding. Ultimately, they hope to convince the Indonesian government to enact laws that specifically protect the species. They have some traction: officials have already sought Simeon’s advice on where to implement stricter protections for endangered marine animals.

As Kyne swims toward the ocean floor, the water grows thick with debris. He can barely see the bottle in his hand when he reaches the sandy bottom, unscrews the lid, and fills it with seawater that he hopes will contain the next clue in his team’s long quest. The clown wedgefish may remain a shrinking target in a murky sea, and Kyne has yet to see one alive. But now, as he caps the bottle and swims for the surface, he’s confident the species is still hanging on, somewhere beyond the silt and trash. McDavitt keeps finding evidence of the fish on Facebook, including several specimens from a new location on the Sumatran coast. All the team has to do is find them IRL—in real life.