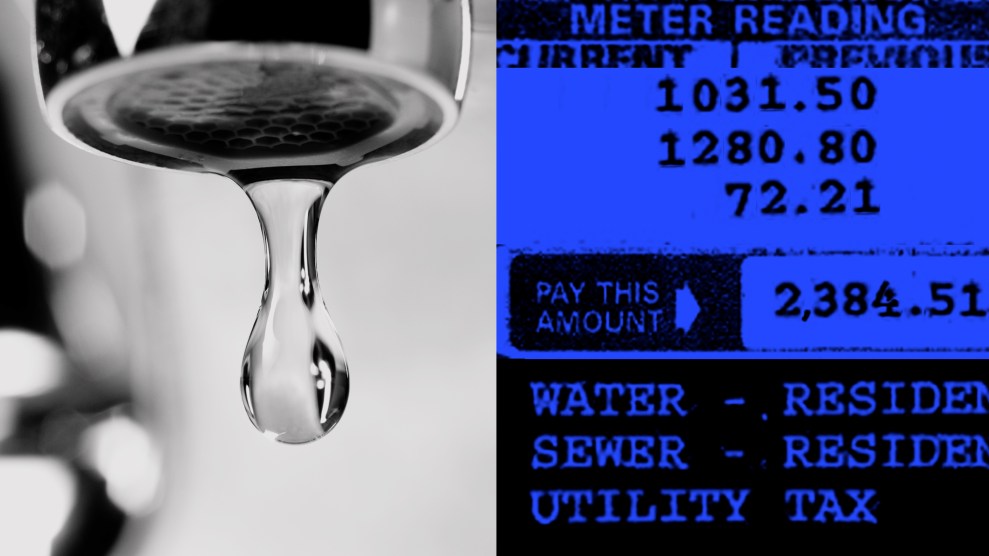

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

When Tyrone Pettway saw his water bill in October 2021, he thought it was a typo. The bill was for $2,384.51, some $2,300 more than what he usually owed the Prichard, Alabama, water board every month.

The document claimed Pettway, his wife, and their five kids had used 167,000 gallons of water over the course of the 34-day billing period, amounting to nearly 5,000 gallons a day. But Pettway was sure they had used no more water that month than they normally did: 3,700 gallons total, or about 18 gallons per person per day—much less than the national average of 82 gallons a day per person.

They hired a plumber who said there was no leak on their property. Pettway was not surprised. “If I had a leak, pushing that kind of water, I would see it somewhere,” he told NBC 15 News following the incident. “Even if it was underground. It’s going to float up somewhere.” So they disputed the amount. They did not have much choice. Pettway is a self-employed construction worker. He makes enough to provide for his family and his community—he builds ramps for free for disabled people—but that’s about it. Instead of acknowledging Pettway’s concerns, however, the Prichard Water Works and Sewage Board sent him a new bill for November, which took his charges and added extra expenses, bringing the cost to almost $3100, according to court records. Pettway again disputed the bill. In response, his water was shut off.

It was two days before Thanksgiving. The family had to move their holiday plans. They showered at the neighbor’s house and brought in water from outside sources to drink. “It was an emotional strain,” said Roger Varner, a lawyer who Pettway hired. “You have to say to your son or daughter, ‘We have to bathe elsewhere because I can’t afford to provide as a parent.’”

After the technician left, Pettway found Varner, a young Black man and rising star attorney in Mobile, a city seven minutes south of Prichard. Varner had never heard anything about Prichard Water before meeting Pettway. But once he did, 10 other Prichard residents came to him with similar stories. In May, he filed a complaint against Prichard Water for negligence, breach of contract, and deceptive trade practices, among other things. “Prichard is one of the poorest cities in Alabama,” Varner told me, referring to the fact that 30 percent of the nearly 19,000 residents live in poverty and the median household income is $32,900. “These are just completely unpayable bills.”

Prichard is not alone in facing astronomical water bills. They are a problem in communities of color across the country, where repairs of decaying infrastructure have not kept apace with inflation. “These issues are pervasive,” Marccus Hendricks, a professor of urban studies and environmental planning at the University of Maryland, told the Bloomberg School of Public Health’s podcast last year. “There are cities, both big and small across the nation that are suffering from infrastructure in disrepair.”

Some argue that the trouble with Prichard Water Works & Sewage Board began in early 2018, when members of the board allegedly began embezzling public funds. An early 2022 joint FBI-Mobile sheriff raid found items ranging from Gucci bags to plasma TVs hidden away at the home of Water Board manager Nia Bradley. Further investigation led to Bradley’s arrest and subsequent charges of theft for embezzling as much as $3 million between 2018 and 2021, according to a local news station. Since then, several other Prichard Water employees have been arrested on similar charges. Mobile County District Attorney Ashley Rich said during a press conference that residents’ high-water bills were also part of the investigation, AL.com reported. Ross, the water board’s own attorney, called it “the worst case of public corruption I have ever seen.” (Bradley’s lawyers have said some of the purchases were authorized as part of her compensation package and denied the existence of other purchases.)

Meanwhile, the pipes were falling into disrepair. In the weeks before the raid, Prichard Water asked the Alabama Department of Environmental Management, which supervises utilities and enforces environmental policy in the state, to award it over $300 million for infrastructure projects, including repairing leaks. ADEM commented that it was the highest ask of any Alabama utility. In a statement at that time, ADEM External Affairs Chief Lynn Battle wrote, “ADEM will prioritize funding based on financial and engineering needs.” ADEM awarded Prichard $400,000, about 13 percent of their original request.

A later request for funds by Prichard Water to the Alabama’s Department of Environmental Management’s Clean Water State Revolving Fund—made in September 2022, after Bradley and her co-conspirators were off the board—was also denied. In an email to Prichard Water, ADEM stated the utility “failed to demonstrate the technical, financial and managerial ability to operate and maintain the facilities over the useful life and to repay the loan.” Six months later, the federal government filed a complaint under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act against the Alabama Department of Environmental Management for “withholding resources from communities of color lacking proper sanitation access.” Despite its fair share of sewage problems, Prichard was not included in the complaint, which focused on the unique disparities in the Black Belt.

While ADEM was denying Prichard resources, they were also monitoring the dangers of the city’s water system. “The state of disrepair of Prichard’s water lines cannot be overstated,” the department concluded in a report released this year. They explained that “with such infrastructure conditions, providing reliable water service remains challenging…a matter that warrants expedited attention for the protection of public health.” But their most notable finding, perhaps, was that between between 2019 and 2022, as much as 60 percent of the water Prichard Water bought to serve residents was lost. ADEM’s recommended system water loss is 15 percent. While some of this is due to expected causes—liked documented water main breaks or water used for fire suppression—the board can’t account for what happened to most of its water, the report concluded. Those losses have cost Prichard Water some $2.7 million per year.

In July, Varner filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of residents and organizations in Alabama Village, connecting the dots between the water loss and the high bills. “Prichard Water Board’s water system has at all material times experienced high levels of water loss due to poor and aging infrastructure,” his case alleges. “This led to a reduction of water quality for customers and lead to a financial drain on customers.”

Ross maintains that the two are not related. “There’s a lot of leakage,” he admitted. But, he insisted, it’s been contained to the Alabama Village area of Prichard, known for having the worst infrastructure in the area. Yet that doesn’t account for the inexplicably high bill at the Pettway home, just 2 miles from Alabama Village.

The utility’s solution to the leakages is eliminating Alabama Village as a problem. Prichard Water has threatened to end service to the area entirely and has started the process of eminent domain. “Instead of trying to start to help the people of Alabama Village,” said resident Archie Rankin, “they want to abandon Alabama Village.”

All this trouble has gotten Prichard Water into an even deeper hole. Not only are they being sued by their customers, they are being sued by their bank, who are calling on a judge to appoint a receiver to manage the utility. In their suit, Synovus Bank alleges that Prichard Water is “suffering from gross mismanagement, a lack of fiscal integrity, and endangering public safety by failing to maintain vital system infrastructure.”

For Prichard residents, the rising bills are just one problem. The ADEM report notes that “excessive water loss can adversely affect system pressure, potentially leading to public health concerns that would warrant boil water notices.” It also found several instances where chlorine—which is used to protect against bacteria like E. coli—was at significantly lower levels than the required amount. “Potential for inadequate disinfection is an added concern,” the report states.

The mayor has claimed the water is safe to drink; residents are not so sure. Many have begun to boil water or buy it bottled. “We’ve had millions of tons of sewage spilled out in our community,” says local environmental justice activist Carletta Davis, in reference to Prichard’s frequent sewage overflows. “It is our belief that if the infrastructure is so poor, and they’re losing water, then what is stopping the other contaminants from coming into the pipes as well?”

Davis and many others argue that Prichard Water’s problems started long before Bradley was using public money to buy Gucci bags. In fact, for Davis, the story is more complicated than “Prichard Water is bad.” While she was one of many who called for Bradley’s ouster, she feels the gutpunch of déjà vu. Just years before, Davis was fighting against a leak of Mercaptan, the bad-smelling chemical that is added to natural gas as an alert for leak protection and is itself dangerous—it can cause skin irritation, breathing problems, and even comas. The leakage went ignored for over 8 years, despite Davis and others’ activism.

“We have suffered for years from disinvestment,” Davis said. Case in point is the historic redlining in the area, which was once a hub of industry with its own railroad station. No formal study has been done of lending practices in Prichard, but Mapping Inequality, a project of University of Richmond that looks at New Deal era redlining, has documented how, in nearby Mobile, areas with Black residents and business were marked by banks as “hazardous” and labeled with notes such as “should be demolished.” Even today, Mobile is ranked the worst in Alabama for modern-day redlining, a now-illegal lending practice. Black residents are more than 5 times less likely to be approved for a loan than other residents.

There is a strong correlation between the value of housing and the potential for community infrastructure. “The vast majority of spending on local water services in the US is by local governments,” says Erika Smull an advisor at Breckenridge Capitol. “We live in a country with extreme decentralization of fiscal responsibility for water infrastructure. It is truly the fiscal responsibility of local municipalities.” But local municipalities are funded by local taxpayers, and not all taxpayers have been given the same opportunities to accrue capital. “If you really want to understand the quality and condition of broader neighborhood infrastructure, you can usually look to the quality and condition of the housing stock,” said Hendricks, the public health professor. “That is directly connected to a broader community tax base, which is the fundamental financing mechanism for community infrastructure.”

All this is compounded by the fact that it is harder for Black communities to get outside funding for repairs. A recent study by Smull found that there was a penalty against communities of color in the municipal bond market, which is the main source of funding for projects in low-income communities. “Rating agencies aren’t supposed to look at race,” Smull explained to me. It is not so simple, however. “Race is so intertwined with all the variables that would impact overall credit.”

“We are not unlike many other black communities around the country,” says Davis. “Our community just really has been totally neglected.” She worries that focusing too much on the board’s embezzlement will contribute to the stereotype that “Black people can’t manage or run anything,” and she wants people to look at the larger picture: Even the most talented water board does not have the ability to fix a broken water system without adequate resources. “These majority white cities and majority white communities. They’re flooding them with grants, Community Development Block Grant funding, and all this other kind of stuff. And they thrive,” says Davis. “And it’s like, well, try withholding some of that money from over there and see what will happen.”

But Davis is not waiting around for ADEM to rethink its approach. The Southern Poverty Law Center recently partnered with We Matter Eight Mile Community Association, the local environmental justice group Davis leads, to investigate the finances and distribution of funds in both Prichard Water and the Alabama Department of Environmental Management.

“We are requesting records, we’re investigating.” Crystal McElrath, a SPLC senior supervising attorney said at a local meeting in July. “We know that when you take our access to water, when you take our access to healthcare, when you take our land, you are stripping us over and over and over again and preventing our ability to build generational wealth. And the Black people in America, Black people in the South, have been dealing with this on so many fronts over and over and over again.”

And while the Pettway family remains on the hook for a multiple-thousand-dollar charge, the small army of residents battling unfair bills that he has helped build is not going anywhere. “You can’t terminate their water because you haven’t done your job as a government,” says Varner.