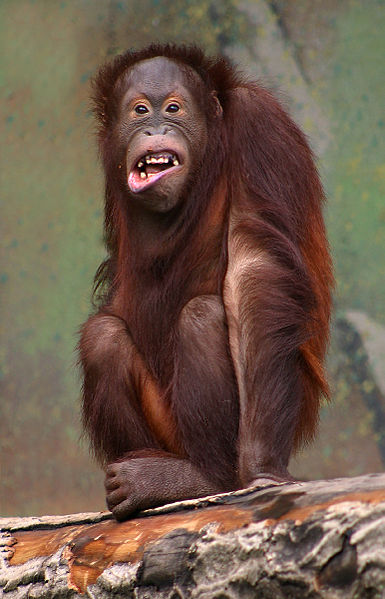

A mother Orangutan and her baby.Media Drum World/Zuma

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The high intelligence levels of orangutans have long been recognized, partly due to their practical skills such as using tools to crack nuts and forage for insects. But new research suggests the primate has another handy skill in its repertoire: applying medicinal herbs.

Researchers say they have observed a male Sumatran orangutan treating an open facial wound with sap and chewed leaves from a plant known to have anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving properties.

It is not the first time wild animals have been spotted self-medicating: Among other examples, Bornean orangutans have been seen rubbing their arms and legs with chewed leaves from a plant used by humans to treat sore muscles, while chimpanzees have been recorded chewing plants known to treat worm infections and applying insects to wounds.

However, the new discovery is the first time a wild animal has been observed treating open wounds with a substance known to have medicinal properties.

“In the chimpanzee case they used insects and unfortunately it was never found out whether these insects really promote wound healing. Whereas in our case, the orangutan used the plant, and this plant has known medical properties,” said Dr Caroline Schuppli, senior author of the research based at Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Germany.

The team say the findings offer insight into the origins of human wound care—the treatment of which was first mentioned in a medical manuscript dating to 2200 BC.

“It definitely shows that these basic cognitive capacities that you need to come up with a behavior like this…were present at the time of our last common ancestor most likely,” said Schuppli. “So that that reaches back very, very far.”

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, Schuppli and colleagues report how they made the discovery while working in a research area of a protected rainforest in Indonesia.

The team describe how, while tracking a male Sumatran orangutan called Rakus, they noticed he had a fresh facial wound—probably the result of a scrap with another male. Three days later, Rakus was seen feeding on the stem and leaves of Fibraurea tinctoria—a type of liana climbing vine.

Then he did something unexpected. “Thirteen minutes after Rakus had started feeding on the liana, he began chewing the leaves without swallowing them and using his fingers to apply the plant juice from his mouth directly on to his facial wound,” the researchers write.

Not only did Rakus repeat the actions, but shortly afterwards he smeared the entire wound with the chewed leaves until it was fully covered. Five days later the facial wound was closed, while within a few weeks it had healed, leaving only a small scar.

The team say the plant used by Rakus is known to contain substances with antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-fungal, antioxidant, pain-killing and anticarcinogenic properties, among other attributes, while this and related liana species are used in traditional medicine “to treat various diseases, such as dysentery, diabetes and malaria.”

It remains unclear whether Rakus figured the process out for himself or learned it from another orangutan, although it has not been seen in any other individual.

Schuppli added that Rakus appeared to have used the plant intentionally. “It shows that he, to some extent, has the cognitive capacities that he needs to treat the wound with some medically active plants,” she said. “But we really don’t know how much he understands.”