<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/hynkle/5026480882/sizes/z/in/photostream/">hynkle</a>/Flickr

Every year in the Chesapeake Bay, an algae bloom spreads out, sucking oxygen out of the water and destroying fish habitat. This year’s “dead zone” stretches from Baltimore Harbor to south of the Potomac River, the Washington Post reports. It’s on track to become the bay’s largest ever. Already, fully a third of the bay—once one of the globe’s most productive fisheries—is incapable of supporting sea life.

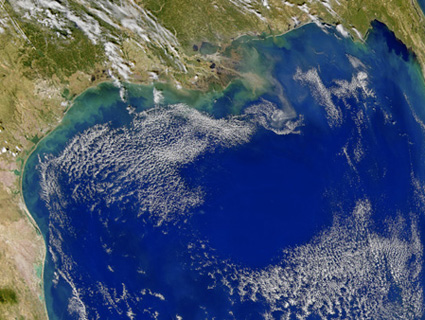

Meanwhile, down the Gulf of Mexico, the same thing is happening on an even grander scale. According to Texas A&M University researchers, this year’s Gulf dead zone blots out 3,300 square miles of our nation’s most important fishery—”roughly the size of Delaware and Rhode Island combined,” they calculate. Before the year’s out, it could as much as triple in size, the researchers fear, which would make it the Gulf’s largest hypoxic (oxygen-depleted) area ever.

Why such huge dead zones this year? The immediate cause is heavy rains in both the Midwest and the Northeast, which wash vast amounts of nutrients down streams and rivers and into the sea at key river delta areas like the Chesapeake and the Gulf. There, the nutrients provide a feast for algae, and voilà, dead zones.

But the ultimate source of the nitrogen and phosphorus that feed the algae blooms is industrial agriculture: millions of acres of fertilizer-guzzling corn farms in the Mississippi River watershed and massive concentrations of chicken farms right on the banks of the Chesapeake.

In both cases, agribusiness groups deny responsibility for the phenomenon. Their case was aptly summed up by this 2010 post on the National Corn Growers Association blog:

Urban areas contribute a large amount of nitrogen. Golf courses lay out copious amounts of chemicals to stay a lush green even in areas where they may be the only green grass for miles. City streets, even apartment buildings contribute as the rain washes away the chemicals that make modern urban life possible.

But this is pure industry hucksterism. In the Gulf, according to the US Geological Survey, “agricultural sources contribute more than 70 percent of the nitrogen and phosphorus…versus only 9 to 12 percent from urban sources.” As for the Chesapeake, Pew Environment Group has just released a major report called Big Chicken (PDF) that demonstrates the poultry industry’s devastating impact on the bay. The poultry industry has chosen to concentrate enormous production on the bay’s eastern shore, known as the Delmarva Peninsula. The factory-scale poultry farms there generate more than 40 million cubic feet of nitrogen- and phosphorus-rich manure—much more than can be effectively absorbed by the area’s limited farmland as fertilizer. As a result, all too much of it runs off into the bay, Pew shows.

In a sense, the Gulf and Chesapeake dead zones are linked. In the Midwest, farmers grow huge amounts of corn using annual cascades of synthetic nitrogen and mined phosphorus. The corn crop only takes up so much of these fertilizers (about 40 percent, in the case of nitrogen), leaving the rest available to runoff into the Mississippi. Then some portion of that very corn goes to the feed the millions of birds in Delmarva’s poultry factories—some of which exits them in the form of nutrient-rich manure prone to leaching into the bay. Growing a massive corn crop and feeding about 40 percent of it to confined animals essentially gives us two dead zones for the price of one.

And in doing so, we’re sacrificing what could be robust, self-sustaining wild fisheries for resource-intensive factory farms churning out dodgy meat. In the end, only shareholders in the big agribusiness firms benefit from this bargain.