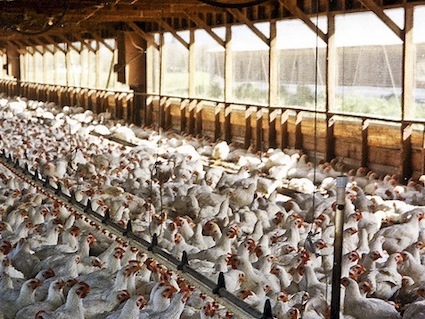

Here's how not to avoid salmonella superbugs. <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/farmsanctuary1/2163655674/sizes/z/in/photostream/">Farm Sanctuary</a>/Flickr

I’ve been writing a bit recently about the problem of antibiotic-resistant pathogens on factory animal farms, which are emerging as a lethal—and expensive—public-health threat.

The two major regulatory agencies that have a say in the matter—the USDA and the FDA—have acknowledged the severity of the problem, as has our main public-health-monitoring outfit, the CDC. Even the Government Accounting Office (GAO) has gotten into the act! None of this has led the federal government to actually crack down on the practice of feeding animals daily subtherapeutic doses of antibiotics.

Judging from the inaction, you’d think there’s simply no alternative to antibiotics as an integral part of livestock feed—and resistant bacteria as an inevitable product of meat factories, along with all the pork chops and chicken wings.

Turns out though, there is an alternative: Just ban antibiotics on farms, and force producers to adopt organic standards. In a study just published in Environmental Health Perspectives, a team of researchers looked at 20 large-scale chicken facilities—10 conventional, and 10 that had recently converted to organic standards, which include a ban on antibiotics. The result: The organic facilities had sharply lower presence of drug-resistant bacteria.

Here’s how lead researcher Amy Sapkota of the University of Maryland School of Public Health described the findings in an interview with the Washington Post:

We initially hypothesized that we would see some differences in on-farm levels of antibiotic-resistant enterococci when poultry farms transitioned to organic practices…But we were surprised to see that the differences were so significant across several different classes of antibiotics even in the very first flock that was produced after the transition to organic standards. [Emphasis mine.]

These results align with those of another recent research paper that compared conventional and organic poultry houses run by a single company. In that study, the organic facilities had not been recently converted—they had been organic for some time. Again, huge differences turned up. The conventionally raised birds were six times more likely to carry salmonella than the organic birds. And here’s the kicker: 40 percent of the salmonella carried by the conventional birds had resistance to no fewer than six different antibiotics—vs. none of the salmonella from the organic birds.

Crucially, both studies are looking at large-scale organic operations—what Michael Pollan labeled “industrial organic” in The Omnivore’s Dilemma. According to a lucid explanation of USDA organic poultry standards [PDF] from the National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service (ATTRA), organic birds have to get “access to the outdoors for exercise areas, fresh air and sunlight.” But in The Omnivore’s Dilemma, Pollan demonstrated that that rule is often implemented as a farce—birds have access to a door to the outdoors, but they never utilize it. Nor are there any stipulations on how densely the birds can be housed, ATTRA reports.

However, organic code forbids antibiotics and other “animal drugs.” And without being able to resort to daily lashings of pharmaceuticals, operators probably can’t stuff as many birds in an organically managed house as they do in a conventionally grown one. “Most [organic producers] look for at least 1.5 square feet (0.14 square meters) per bird,” ATTRA states. In conventional chicken houses where the feed is laced with antibiotics, the birds get about a half a square foot each, according to this Humane Society of the United States document [PDF].

What all of this suggests is that antibiotics and the resistant bugs they generate are not an inevitable aspect of poultry production; they’re an inevitable aspect of a highly consolidated food system. Recently, I wrote about how the ecological calamities of pork production could be largely solved by deintensifying it and spreading it out. The same is true of poultry production.

In an excellent recent report called “Big Chicken: Pollution and Industrial Poultry Production in America,” the Pew Trusts reports that the number of chickens raised each year in the United States jumped from 580 million in the 1950s to nearly 9 billion today.

Astonishingly, just four huge companies process 60 percent of those birds in a handful of gigantic plants—and as they took control over the market, they closed small slaughterhouses and forced 1.5 million farms, widely dispersed across the country, to either dramatically scale up their poultry operations or exit the business. Since the ’50s, the Pew report states, “the number of producers has plummeted by 98 percent, from 1.6 million to just over 27,000 and concentrated in just 15 states.” The average poultry farm now churns out 600,000 chickens per year.

The result, of course, is the destruction of highly productive ecosystems like the Chesapeake Bay. All for a whole bunch of flavorless chicken laced with antibiotic-resistant superbugs. If only there were a better way! Oh, wait—there is.