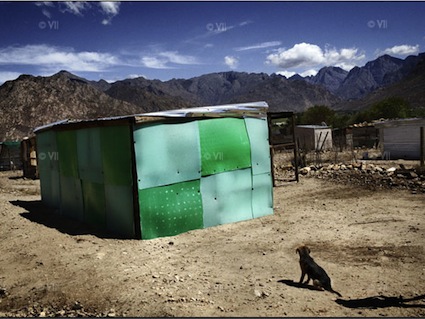

A farm worker collects grapes during harvest time in South Africa’s wine country. Marcus Bleasdale/Human Rights WatchYesterday, South Africa-born filmmaker Adam Welz and I had an exchange on my recent post on labor conditions in South Africa’s wine country, which discussed a Human Rights Watch report on the topic. I asked the report’s lead researcher and author, human-rights lawyer and writer Kaitlin Y. Cordes, to join the conversation. Her response follows.

A farm worker collects grapes during harvest time in South Africa’s wine country. Marcus Bleasdale/Human Rights WatchYesterday, South Africa-born filmmaker Adam Welz and I had an exchange on my recent post on labor conditions in South Africa’s wine country, which discussed a Human Rights Watch report on the topic. I asked the report’s lead researcher and author, human-rights lawyer and writer Kaitlin Y. Cordes, to join the conversation. Her response follows.

In the course of interviewing over 260 people about the human rights situation of farmworkers and farm dwellers in the Western Cape province of South Africa, my colleagues and I uncovered a range of exploitative conditions and rights abuses. The information from these interviews were documented in Human Rights Watch’s report, Ripe with Abuse: Human Rights Conditions in South Africa’s Fruit and Wine Industries, which was subsequently discussed in Tom Philpott’s article, “South Africa’s Wine Woes.”

The stories I was told by farmworkers and farm dwellers ranged in severity and composition, but what was perhaps most astonishing to me was that very few of the workers with whom I spoke had no problems of which to tell me. Of course, this does not mean that there are no farms without problems. As the report points out, conditions on farms vary, and some farm owners go beyond full compliance with the law to provide a number of other benefits to workers. Ripe with Abuse enumerates a number of these better practices. Yet the situations I discovered were not simply isolated incidents.

In my opinion, one of the most important points in the Mother Jones coverage of Human Rights Watch’s report is noting that these problems are not unique to South Africa. Indeed, last year, Human Rights Watch documented human rights abuses against child farmworkers in the United States and foreign migrant farmworkers in Kazakhstan. Just a few weeks ago, The New York Times hosted an online debate about foreign migrant workers in the US agricultural sector—and it was noted that wages would have to be increased 40 percent simply to rise above the federal poverty line. This is not a geographically isolated problem. (I also want to clarify that the HRW report documented abuses against workers in both the fruit and wine industries, and that the majority of the farms covered in the research were actually fruit farms.)

The release of Ripe with Abuse caused a frenzy of media coverage in South Africa and abroad; it also prompted a number of stakeholder responses that were at times emotional or politicized. Industry representatives and farmers’ associations said the report was biased; one trade union said the report was too weak and did not show the real misery that farmworkers confront. Government response was varied, although the Minister of Agriculture summoned us to present our findings to her and all the provincial Ministers of Agriculture, welcoming our report and asking us to do similar research in other parts of the country. In this flurry of responses, not a single inaccuracy has been brought to our attention; criticism leveled by industry instead focused on the fact that this could damage South African exports, with warnings that Human Rights Watch’s work might cause job losses for workers. In addition, Human Rights Watch was asked to name farms, so that high-level government officials could personally address problems, as well as to give consumers peace of mind over their purchases.

This brings me to Adam Welz’s criticism of Mother Jones’s coverage of the report, as well as, implicitly, criticism of the report itself. There are two main criticisms that are important to address: (1) the argument that actionable information should be provided to readers; (2) the argument that many workers have no other job choices.

The vast majority of the farmworkers with whom I spoke were scared to speak with an outsider who could identify them; all interviews that I conducted with farmworkers and farm dwellers were thus done in confidentiality, to protect against possible negative repercussions. Farmworkers have good reason to be scared: in South Africa, they often depend on farm owners for multiple benefits—not just their jobs, but also their homes, their transport, and sometimes even their children’s education. Losing a farm job can be devastating.

The confidentiality that we promised workers meant that we were unable to name farms, because of the possibility that interviews then could be traced to workers. Moreover, these were not isolated incidents, and I did not uncover every farm with exploitative conditions (nor, conversely, every farm with better practices). As the report points out, the government has committed to laws that protect farmworkers and farm dwellers, yet has failed to monitor and enforce those laws effectively. The primary solution for protecting these workers is simply to get the government to enforce its laws better.

It could start by hiring more labor inspectors; at the time of research, there were only 107 labor inspectors responsible for enforcing labor laws on approximately 6000 farms, as well as every other workplace in the province. It’s no wonder that most workers had never even heard of an inspector coming to the farm, or that one prominent wine farm told me that they had never received a visit from a labor inspector in ten years of operation. In this context, with the potential threats to workers, the large number of farms that I was not able to visit, and the failure of the government to enforce its laws, naming farms is not as helpful as simply getting the government to do its job better.

As a consumer, I know how frustrating it can be to read about poor labor conditions and to not be given the names of products to avoid or to seek out. But the government and other stakeholders need to make stronger efforts to improve labor and housing conditions for workers. Adam points to the Biodiversity Wine Initiative (BWI) as an example of progressive farms, but the HRW report was not focused on conservation issues. In respect of the wine industry, however, the Wine Industry Ethical Trade Association (WIETA) does exist, and is discussed in the report.

Yet WIETA covers only a small percentage of producers, does not require audits down the supply chain to ensure good working conditions on all supplying farms, and, as pointed out by a prominent South African wine critic, is mostly concerned with ensuring that accredited members comply with the law. If the wine industry wants to assure consumers that labor conditions are good, it must do much more to strengthen WIETA and expand its scope.

Having said this, Human Rights Watch recognizes that consumer pressure and involvement can be crucial. This is why we have described positive steps that consumers can take, including by explicitly asking retailers for products that are grown, harvested, packed, and bottled by producers who are subject to ethical audits.

This leads me to the second criticism: the argument that many workers have no other job choices. It is true that unemployment in South Africa is very high, and workers in rural areas have particularly few options. Our goal has never been to put these workers out of a job; even our press release was careful to point out that we were not calling for a boycott. At the same time, however, it is crucial to recognize that the South African government has committed to domestic laws, as well as to international and regional human rights conventions, that are meant to provide greater protections to workers than many currently receive.

The fact that jobs are important does not mean that employers can flout the laws. We cannot shy away from urging the government to do its job, or from asking farmers’ associations and industry bodies to assist. Avoiding uncomfortable discussions is not the answer. Rather, seeking sustainable solutions to improve labor conditions across the farming sector is the best way to ensure that South Africans in rural areas have jobs that allow them to live with dignity.