<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/ammichaels/8122518497/sizes/z/in/photostream/" target="_blank">cheeseslave</a>/Flickr

“Come at the king, you best not miss,” the character Omar famously observed on The Wire. Does the law of the streets apply to the politics of food? Writing in the The New York Times Magazine last month, Michael Pollan laid down the gauntlet on Prop. 37, the California ballot initiative that would have required labeling of genetically modified foods. “One of the more interesting things we will learn on Nov. 6 is whether or not there is a ‘food movement’ in America worthy of the name—that is, an organized force in our politics capable of demanding change in the food system,” he wrote.

Pollan ended his essay by suggesting that passage of Prop. 37 would be a sure way to convince President Obama of the importance of food-system reform.

Over the last four years I’ve had occasion to speak to several people who have personally lobbied the president on various food issues, including G.M. labeling, and from what I can gather, Obama’s attitude toward the food movement has always been: What movement? I don’t see it. Show me. On Nov. 6, the voters of California will have the opportunity to do just that.

And make no mistake, Prop. 37 was the food-system equivalent to a lunge at the king. No fewer than two massive sectors of the established food economy saw it as a threat: the GMO seed/agrichemical industry, led by giant companies Monsanto, DuPont, Dow, and Bayer; and the food-processing/junk-food industries who transform GMO crops into profitable products, led by Kraft, Nestle, Coca-Cola, and their ilk. Collectively, these companies represent billions in annual profits; and they perceived a material threat to their bottom lines in the labeling requirement, as evidenced by the gusher of cash they poured into defeating it (more on that below).

Well, now the deed is done. We’ll never know if Prop. 37 would have emboldened Obama, now re-elected, to change course on food policy. What does its failure mean for what Pollan calls the food movement?

First, it’s important to ponder the question of what the food movement is. I see it as a loose, widely distributed thing—it contains a broad range of people, from grandmotherly community gardeners in some of New York City’s poorest neighborhoods to high-profile writers like Pollan. Like any social movement, it’s an unwieldy, occasionally self-contradictory coalition, with both grassroots and inside-politics elements. The goals, it seems to me, are twofold (most strands of the movement emphasize one or the other, but at least dabble in both):

- To temper and reform the damaging aspects of the existing food system, everything from low pay for workers to health-ruining junk food to pollution from large-scale livestock farms to corporate consolidation; and

- To create alternative, non-corporate-owned food networks that answer more directly to farmers, consumers, and communities.

Prop. 37 was very much within the realm of goal number one. And it was by far the boldest and most organized move in that direction to date. As I and others have noted, the initiative—assuming that it would have survived Monsanto’s inevitable legal challenges—likely would have inspired the processed-food industry to label foods everywhere, since making separate labels for California would have been costly and troublesome. And national GMO labeling probably would have sparked a real national conversation on just what’s going on with our food supply—how it got so homogenized, uniform, and reliant on a narrow base of seed types owned by a tiny number of giant companies. Prop. 37 was a kind of quasi-national referendum on corporate domination of the food system. That’s why national-level writers like Pollan, Mark Bittman, Marion Nestle, myself, and others go so involved with it.

Now that the referendum failed in a popular election, we have to ask, pace Pollan, whether there is a “an organized force in our politics capable of demanding change in the food system.”

I think the answer is an obvious, “yes.” First of all, Prop. 37 isn’t the movement’s first incursion into California’s ballot-initiative sweepstakes. Back in 2008, animal-welfare groups—very much a strand of the food movement—organized Proposition 2, which mandated that egg-laying hens, veal calves, and pregnant pigs not be confined to tight cages. There’s not much large-scale veal or hog production in California, but commercial egg interests are substantial, and they raised $8.5 million to fight the proposal. In retrospect, I’m surprised they didn’t raise much more. The US egg industry is big and relatively consolidated—here’s some work I did a couple of years ago to untangle its complex structure—but it’s not nearly as vast or top-heavy as the meat industry.

Gigantic meat companies like Tyson, JBS, and Smithfield might have been expected to pitch in to the effort to beat back Prop 2, on the grounds that a California confinement restrictions could be the peak of a very slippery regulatory slope.

For whatever reason, they didn’t (list of donors here); and Prop. 2 supporters, led by the Humane Society of the United States, actually managed to raise more money—$10.3 million total—and the initiative won by a margin of nearly two-to-one. The Prop. 2 victory was just what Pollan recently called for—a flexing of political muscle by the food movement. And the triumph has national implications—the national egg industry, after fighting Prop. 2 bitterly, is now joining forces with its erstwhile adversary, the Human Society, to take California’s cage standards national. The logic: It’s more economical to have a single national standard than a hodgepodge.

Why didn’t Prop. 37 enjoy similar success? Some have pointed to the string of prominent state newspaper editorial boards that opposed it, including the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Sacramento Bee. But that can’t be right; those same papers also came out against Prop. 2. Who takes newspaper endorsements seriously any more?

The obvious difference is money. Prop. 2 went after a relatively fringe sector of Big Food, eggs, where Prop. 37 went against big money interests. In short, Prop. 37 got crushed under fat stacks of cash: its supporters raised $8.7 million, vs. $45.6 million for its opponents. In other words, while Prop. 2 supporters managed to raise more than the industry it went up against, Prop. 37 got outspent by a margin of five dollars to one. The two biggest donors to the anti-labeling effort, Monsanto and DuPont (list of leading donors to both sides here), contributed a combined $13.5 million. That’s more than one and a half times the entire cash hoard that went into fighting the caged-hen proposition.

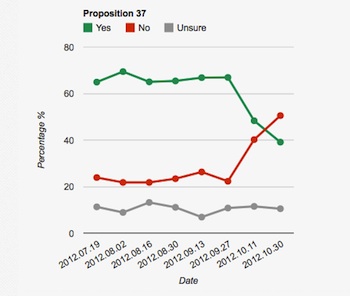

On Oct. 1. “No on Prop. 37” started its TV-ad blitz. Pepperdine University/California Business RoundtableWhat do you get for $45.6 million? You get a slick, relentless, truth–challenged campaign, crafted by veteran GOP political hand and former tobacco flack Thomas Hiltachk. The “No on Prop. 37” campaign began its television ad blitz on Oct. 1, a campaign spokesperson told me. At the time, Prop. 37 was leading in the Pepperdine University/California Business Roundtable poll by a factor of three to one. By the time of the next poll, Oct. 11, the race had tightened to a near dead heat—the proposition’s slide toward defeat had begun.

On Oct. 1. “No on Prop. 37” started its TV-ad blitz. Pepperdine University/California Business RoundtableWhat do you get for $45.6 million? You get a slick, relentless, truth–challenged campaign, crafted by veteran GOP political hand and former tobacco flack Thomas Hiltachk. The “No on Prop. 37” campaign began its television ad blitz on Oct. 1, a campaign spokesperson told me. At the time, Prop. 37 was leading in the Pepperdine University/California Business Roundtable poll by a factor of three to one. By the time of the next poll, Oct. 11, the race had tightened to a near dead heat—the proposition’s slide toward defeat had begun.

By the day before the election, its fate had become obvious. “In a campaign reminiscent of this summer’s successful fight against a proposed tobacco tax in California, opposition funded by Monsanto Co, DuPont, PepsiCo Inc and others unleashed waves of TV and radio advertisements against Proposition 37 and managed to turn the tide of public opinion,” Reuters reported Monday.

Given the formidability and deep pockets of the opposition, I think it’s overblown to treat Prop 37 as a pass-fail test of the food movement’s political viability. The movement made a strong move at the king and missed, but it isn’t going anywhere. George Kimbrell, who, as senior attorney for the Center for Food Safety, helped craft the legislation, told me that activists are gathering signatures to push a labeling initiative in the state of Washington in 2013, and he expects to see labeling bills in statehouses in Maine, Oregon, New Mexico, and others. “You try and try and fail, and eventually you succeed,” he said.

Meanwhile, explicitly political efforts like Prop. 37 are only one part of the food movement. The other part, the effort to build viable, non-corporate alternatives to big food, moves forward in thousands of on-the-ground projects nationwide. These efforts proceed completely independent of and unimpeded by the machinations of Monsanto and its ilk. One of my favorite ones is Added Value in Red Hook, Brooklyn, which has been growing fresh food, running a farmers market, employing teens, and partnering with schools in a low-income neighborhood for more than a decade. (Here’s my 2006 profile of Added Value). The project suffered a blow stronger than any that even Monsanto could dole out last week—Super Storm Sandy flooded its 2.75 acre Red Hook Community Farm with three feet of seawater last week, wiping out its fall harvest. But as you’ll see in the video below, Added Value is mounting a strong comeback, borne along by strong community support. So, I predict, will the broad, multifaceted food movement.