<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&language=en&ref_site=photo&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&use_local_boost=1&searchterm=grocery%20aisle&show_color_wheel=1&orient=&commercial_ok=&media_type=images&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&color=&page=1&inline=221971015">Tooykrub</a>/Shutterstock

Ever been advised to “eat like your grandmother”—that is, to seek food that’s prepared in ways that would be recognized a generation or two ago, untainted by the evils of industrialization? That’s nonsense, writes Rachel Laudan in a rollicking essay recently published in Jacobin.

Her polemic is actually a reprint. It originally appeared in Gastronomica way back in 2001—five years before the publication of Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, at the dawn of a boom in farmers markets and other ways to “know your farmer” and “eat local.” And yet it’s just as bracing to read today as it was then.

The backlash against stuff like chicken nuggets and boxed mac ‘n’ cheese is “based not on history but on a fairy tale,” Laudan writes. Food-system reformers tend to evoke a “sunlit past” of wholesome, home-cooked meals, to which she offers a stark riposte: “It never existed.”

Thing is, implicated though I may be in Laudan’s blistering critique, I largely agree with it—with a caveat.

You wouldn’t know it from grazing the virtuous bounty on display at Whole Foods, but securing good food has always been a struggle. Laudan, a historian who has authored a book on food and empire, spices her essay liberally with pungent facts about preindustrial food. “All too often,” she writes, “those who worked the land got by on thin gruels and gritty flatbreads,” because all the good stuff went to their feudal lords and a rising urban merchant class. French peasants “prayed that chestnuts would be sufficient to sustain them from the time when their grain ran out to the harvest still three months away,” while their Italian counterparts “suffered skin eruptions, went mad, and in the worst cases died of pellagra brought on by a diet of maize polenta and water.”

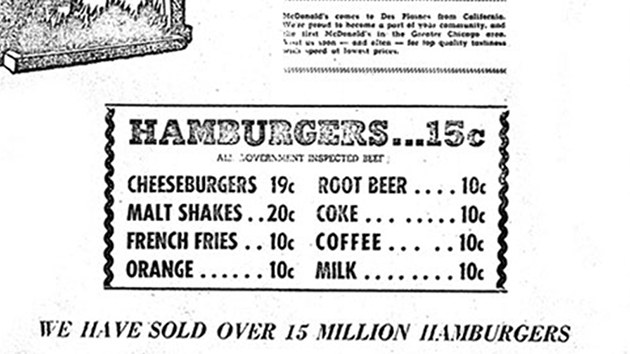

And she notes, as I have with great relish, that fast food is hardly the invention of midcentury US burger kings. “Hunters tracking their prey, fishermen at sea, shepherds tending their flocks, soldiers on campaign, and farmers rushing to get in the harvest all needed food that could be eaten quickly and away from home,” she writes. But the real fast-food action was found in cities, forever packed with people living in tight quarters with few cooking resources:

Before the birth of Christ, Romans were picking up honey cakes and sausages in the Forum. In twelfth-century Hangchow, the Chinese downed noodles, stuffed buns, bowls of soup, and deep-fried confections. In Baghdad of the same period, the townspeople bought ready-cooked meats, salt fish, bread, and a broth of dried chick peas. In the sixteenth century, when the Spanish arrived in Mexico, Mexicans had been enjoying tacos from the market for generations. In the eighteenth century, the French purchased cocoa, apple turnovers, and wine in the boulevards of Paris, while the Japanese savored tea, noodles, and stewed fish.

Yum!

In short, Laudan has delivered an evocative corrective to the culinary romanticism that pervades our farmers markets and farm-to-table culinary temples.

Yet her “plea for culinary modernism” contains its own gaping blind spot. If Laudan’s “culinary Luddites” feast on tales of an imaginary prelapsarian food past, she herself presents a gauzy and romanticized view of industrialized food.

Starting around 1880, she notes, US and European farmers began spreading more fertilizer and using better farm machinery, sparking the agricultural revolution that’s with us today: reliance on hybrid (now genetically modified) seeds, agrichemicals, monocrops. To hear her tell it, it’s been nonstop progress ever since.

For all, Culinary Modernism had provided what was wanted: food that was processed, preservable, industrial, novel, and fast, the food of the elite at a price everyone could afford. Where modern food became available, populations grew taller, stronger, had fewer diseases, and lived longer. Men had choices other than hard agricultural labor, women other than kneeling at the metate (Mexican corn grinder) five hours a day.

What she misses, of course, are the downsides. She celebrates the year-round availability of fruits and vegetables, but doesn’t mention the army of ruthlessly exploited workers (Mexicans in the US West, and in the South, until recently, the descendants of enslaved African Americans) required to plant, tend, and harvest it. Yes, meat, once enjoyed “only on rare occasions” by working people, is now within easy reach of most Americans, but Laudan doesn’t pause to ponder what it means for the people who work for poverty wages in factory-scale slaughterhouses. To speak nothing of fast-food, restaurant, and supermarket workers.

Nor does she ponder the people cut off from industrialized food’s bounty: The nearly 1 billion people, most of them in the Global South, who lack enough to eat—many of whom work on plantation-style farms that provide wealthy consumers with coffee, sugar, bananas, and other fruits and vegetables.

She also evades the ecological question. Large Midwestern farms provide the grain that feeds our teeming factory meat operations. In doing so, they systemically foul water with agrichemicals and hemorrhage topsoil, essentially a fossil resource. Meat farms, meanwhile, have become overreliant on antibiotics—contributing to an antibiotic-resistance crisis that now claims 700,000 lives worldwide. California’s agricultural behemoth, which churns out the bulk of US-grown fruits and vegetables and nearly all US-grown nuts, relies on oversubscribed and rapidly depleting water resources. And so on.

Finally, there’s health. Laudan is right that starvation is mostly a thing of the past in the industrialized world, but she has little to say about how our modern diet is contributing to new forms of misery: high rates of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and cancer.

I share her annoyance at the historical fantasia that often passes for analysis among foodies. The key insight to be drawn from Laudan is that our species has rarely if ever experienced an equitable or sustainable way of feeding itself. But that doesn’t mean we should stop trying—or that monocrops and agrichemicals bring us any closer.