A rusty-patched bumble bee. Smithsonian's National Zoo/Flickr

Domesticated honeybees get all the buzz, but wild bumblebees are in decline too, both globally and here in the United States. What gives? It’s an important question, because while managed honeybees provide half the pollination required by US crops, bumble and other wild bees deliver the other half.

Insecticides used in agriculture are one possible trigger—they exist to kill insects, after all, and bumblebees are insects. But a different kind of farm chemical, one designed to kill fungi that harm crops, has emerged as a possible culprit. A new study by a team of researchers led by Cornell University entomologist Scott McArt adds to the growing dossier of studies pinpointing fungicide as a potential bee killer (see here, here, and here).

In their paper, McArt and his team looked at two factors related to bumblebee decline. The first is that many bumblebee species appear to be confining themselves to ever smaller geographical regions—a phenomenon known as range contraction. The other is a microscopic parasite called Nosema bombi, which has turned up at high rates in bumblebee species known to be deteriorating.

The team analyzed samples of bumblebees from eight species taken by previous researchers from 284 sites across the country between 2007 and 2009. For the areas surrounding each site, the McArt team crunched data for 24 environmental factors that might affect bee health: everything from the level of nearby residential development to the portion of land devoted to forests to the amount of insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides applied by farmers.

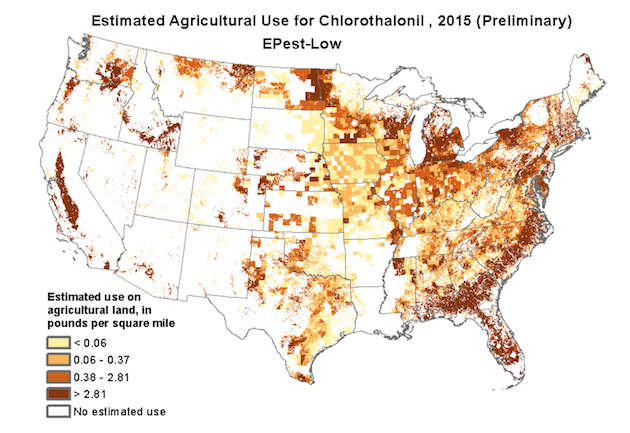

Their goal was to see which of these factors was most closely associated with shrinking habitats and Nosema bombi infections. Total fungicide applications in a given area emerged as the best predictor of range contraction; and a single widely used fungicide, chlorothalonil, proved to be the clearest indicator of Nosema bombi prevalence.

The result wasn’t a total surprise. A 2015 study by University of Wisconsin and US Department of Agriculture researchers found that bumblebee hives exposed to small amounts of chlorothalonil—which is widely used in fruits, vegetables, and orchard crops—”produced fewer workers, lower total bee biomass, and had lighter mother queens than control colonies.”

Here’s a map of where chlorothalonil is used, from the US Geological Survey:

To make matters worse, the fungicides can exacerbate the effect of other types of chemicals. “While most fungicides are relatively nontoxic to bees, many are known to interact synergistically with insecticides, greatly increasing their toxicity to the bees,” McArt said in a press release accompanying the study.

Meanwhile, bumblebees continue to struggle. In its final days, the Obama administration declared the rusty-patched bumblebee, pictured above, as endangered—and its plight is so severe that the Trump administration opted to secure the designation, after hinting it would undo it.

Unlike murders, ecological collapses rarely have a single perpetrator. Rather, they’re caused by a host of culprits working together in ways that are hard to unpack. Add fungicides to the list of potential offenders in the ongoing pollinator crisis.