Trump wine on display at a Trump campaign rally in March 2016Richard Graulich/Palm Beach Post via ZUMA

President Donald Trump is a teetotaler. He has never had a drink, he says, because he saw what booze did to his beloved older brother Freddy, an alcoholic who died at the age of 43. As far back as 1999, when he was first contemplating a run for the White House, Trump told Larry King that if elected, he’d “come down tough on alcohol.” Five years later, he told Esquire, “I never understood why people don’t go after the alcohol companies like they did the tobacco companies. Alcohol is a much worse problem than cigarettes.”

Trump now has the power to follow through on his promise. Instead, though, his administration is helping the alcohol industry attack what could be the first law in the world to mandate cancer warning labels on alcoholic beverages—similar to the warning labels that appear on tobacco products around the globe.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer, an arm of the World Health Organization, declared alcohol a likely carcinogen in 1988, and it’s been linked to seven different types of cancer, including colon and breast cancer. Scientists estimate that alcohol accounts for about 5 percent of all cancer deaths globally, or 426,000 deaths each year. The WHO has recommended warning labels on alcohol as one way of combating cancer, but no country has successfully implemented one so far. Several have been trying, most recently Ireland, which has seen a furious pushback from the industry—as well as opposition from the Trump administration.

In late March, the Office of the US Trade Representative issued its annual report on foreign barriers to trade. It’s a document that lays out all the laws in other countries that the administration views as impediments to selling US products overseas. The report also serves as a roadmap for future challenges to those laws at the World Trade Organization, an international organization that oversees trade agreements and has the power to ensure countries comply with them.

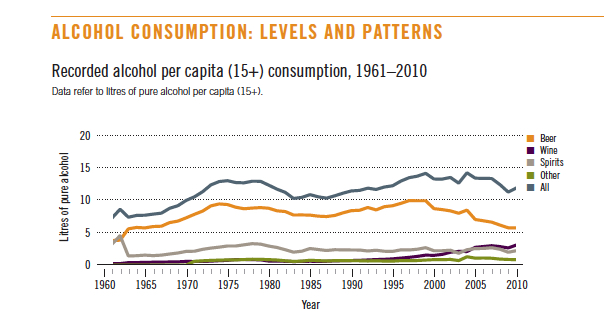

Listed for the first time in this year’s report was legislation pending in Ireland that is designed to help bring down alcohol consumption in a country that’s got a pretty big problem with it. Years in the making, the bill, introduced in 2015, was spurred by evidence that alcohol consumption had skyrocketed in the country since 1960—an increase accompanied by a near tripling of liver disease deaths between 1990 and 2007. By 2001, yearly per capita alcohol consumption in Ireland topped 14 liters (about 3.7 gallons), much higher than in other European countries and the United States. One out of every 10 euros of health spending on hospital discharges in Ireland is related to the use of alcohol, according to the Irish Health Research Board.

Irish alcohol consumption over time

World Health Organization

In the early 2000s, the Irish government attempted to tackle the problem with a series of voluntary, self-regulatory measures supported by industry. Eunan McKinney, an official with the public health group Alcohol Action Ireland, says that by 2009, it was clear the voluntary efforts weren’t working. Per capita consumption was still hovering at around 12 liters per year, an amount Ireland’s primary health research institute worked out to be 41 liters of vodka, 116 bottles of wine, or 445 pints of beer for every adult over the age of 15. (About 20 percent of Irish citizens abstain, so this figure is even higher for actual drinkers.)

In 2013, the Irish government created a task force to develop new ideas to try to bring consumption down to about nine liters per person. Those proposals made their way into the 2015 legislation. (At the time, McKinney was an adviser to the health minister who negotiated and helped craft the bill.) It included restrictions on booze marketing and sports sponsorships, as well “minimum unit pricing,” which was intended to increase the cost of cheap, fortified wine and other such products favored by the down and out. In 2017, as the evidence about alcohol as a carcinogen was becoming increasingly well known, the bill was amended to include a requirement that booze packaging include a warning label informing consumers that alcohol is linked to cancer. The upper house of the Irish parliament passed the bill in December, and it’s now about halfway through the approval process in the lower house. If the law passes, Ireland would become the first country in the world to mandate a cancer warning on alcohol products.

That’s apparently a precedent the alcohol industry doesn’t want to see. Even before the cancer provision was added, the bill had encountered fierce opposition from the industry. After the cancer language was included, industry lobbyists pushed back even harder, insisting that alcohol was no more carcinogenic than “burnt toast.”

Frances Black, an Irish senator and backer of the alcohol bill, decried the industry’s resistance to the labeling provision in a speech before the senate in November. “Over the past year, it’s been really shocking and disheartening to see the intense lobbying and misinformation that has been spread regarding this vital piece of public health legislation,” she said. “This is especially true when it comes to cancer. Like the tobacco lobby in the US in the 60s and 70s, the link between alcohol and cancer, an empirical medical fact, has been regularly denied. I almost couldn’t believe it when I watched one of the most senior and vocal lobbyists against this bill, on Ireland’s national broadcaster just a few weeks ago, flat out denying the link between alcohol and cancer. This is shameful behavior, and we have to call it out.”

The industry opposition hasn’t been contained to the Irish parliament. The US alcohol lobby has been involved in the debate over the Irish bill, too, even though McKinney says US alcohol imports to Ireland total only 15 million euros per year, about .002 percent of the Irish alcohol market.

Because Ireland is a member of the European Union and the new alcohol bill would affect imports, the country was required to notify the European Commission, the EU’s trade administration body, about the proposed labeling requirements. The commission has the power to block the Irish legislation if it concludes the new regulations impede free trade.

Last month, the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States submitted an official statement to the EU commission arguing that the cancer label proposal violates the World Trade Organization’s Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement because, the group alleges, it’s not based on sound science. DISCUS—which represents some of the world’s largest liquor corporations and spent more than $5 million in federal lobbying in the United States last year—insisted that a cancer warning label would be inappropriate because the science “regarding cancer and alcohol consumption is far from settled.”

Christine LoCascio, senior vice president for international trade issues at DISCUS, argued that it would be unfair and confusing to consumers to put a cancer warning label on alcohol products given that drinking is, she claimed, essentially good for people. “Various health authorities and medical studies have found that moderate consumption of alcohol may be associated with certain health benefits for some adults, including a protective effect against cardiovascular disease and diabetes,” she wrote.

That statement is deeply at odds with a decade of research suggesting that the purported benefits of drinking are vastly overblown or nonexistent. Nonetheless, the opposition at the commission is now preventing the Irish lawmakers from enacting their bill for at least the next three months. DISCUS didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Despite the fact that the Irish bill has been pending since 2015, it was never mentioned in previous barriers to trade reports from the Obama administration’s US trade representative. But DISCUS recently found a sympathetic ear in the Trump administration. In 2017, DISCUS asked the USTR to demand that Ireland bring its bill and the new cancer label amendment to the WTO for review so that the industry could weigh in on it. The move is a prerequisite for a country to make a formal complaint, akin to filing a lawsuit, at the WTO.

In his public rhetoric, Trump has been no fan of the WTO, calling it “a disaster for this country” and “unfair to the US.” Nonetheless, his administration complied with the alcohol industry’s request, and a WTO committee is now reviewing the Irish alcohol bill. These opening salvos suggest that the industry may be hoping to block the bill through the WTO, which has the power to impose penalties on countries that violate trade agreements. Such penalties can include allowing an aggrieved country to ban all imports from the country that wronged it.

Jennifer Hillman, a Georgetown law professor and former WTO appellate body member, says the industry doesn’t seem to have much of a case with regard to the warning labels. She says trade agreements allow countries to enact legislation to protect public health and safety, so long as it isn’t more restrictive than necessary and doesn’t discriminate against imported products. The Irish bill applies equally to imported and domestic booze. “If everybody has to do the label, I don’t see how it distorts trade,” Hillman says.

But public health advocates say the alcohol industry’s moves at the WTO are part of a trend in which big corporations have used the mere threat of WTO action to stymie new regulations and deter other countries from making similar attempts. Margaret Chan, the former director-general of the World Health Organization, explained the technique in 2016 at the World Conference on Tobacco or Health. “What industry is aiming for is a domino effect, where countries fall in their resolve, one after another, under the threat of legal action,” she warned.

Indeed, the tobacco industry has been especially aggressive in this area. Recently, for instance, Philip Morris and British Tobacco spent five years challenging a law in Australia that required cigarettes to be sold in plain, drab packages, with nothing but blackened lungs and other graphic warning labels on them. Australia seems to have won its case—the ruling isn’t final yet—but the battle has sent a clear message to other countries that big companies are more than willing to fight expensive, years-long international court battles over public health laws.

A proposed Thai warning label for alcohol that says, “Drinking alcohol leads to inferior sexual performance.”

The Irish labeling proposal isn’t the first one challenged by an alcohol company at the WTO. In 2010, Thailand proposed adding graphic images to warning labels on alcoholic beverages similar to those already used on cigarettes in many places. The Thai law included warnings such as, “Drinking alcohol leads to inferior sexual performance,” and “Drinking alcohol leads to unconsciousness and even death.” The messages were accompanied by graphic photos of people killed in car accidents or a woman being threatened by a drunk man. One even featured the hanging feet of a suicide victim. The world’s alcohol-producing countries came out in force to oppose the measure at the WTO, and Thailand backed down.

The US intervention with the WTO and the EU isn’t sitting well with Irish public health advocates, who see the protests as an end-run around the country’s democratically elected parliament. “Trump and his administration may wish to dictate US-Ireland trading terms, but he can’t, and shouldn’t, tell us how we should inform and protect our own citizens,” says McKinney, invoking the president’s “America First” slogan. “In this instance it’s ‘Irish citizens’ health first’!”