Alice Waters, with cherries. Dvid Sifry/WikiMedia Commons

By the 1960s, food in the rapidly suburbanizing United States generally wasn’t great. There were exceptions, of course—but also plenty of heat-and-serve TV dinners; ground beef cooked with a canned sweet sauce, spooned onto buns, and then declared “Sloppy Joes”; and just-add-water Jello desserts.

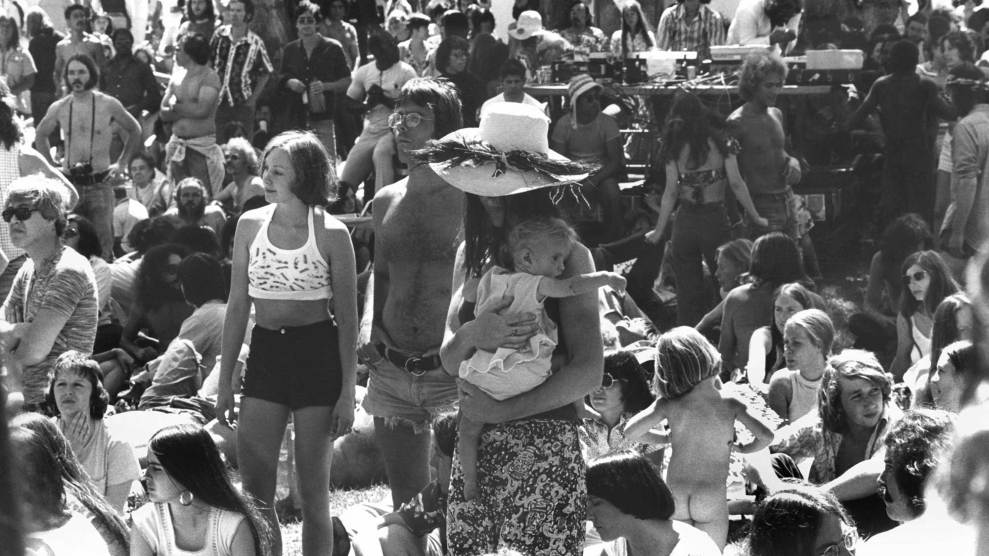

Thankfully, not everyone accepted these culinary affronts sitting down, waiting to be served their next plate of fish sticks and tater tots. In the latest episode of Bite podcast, we look at two mid-century revolts against industrial food, both of which took root in California.

One is hippie food, which basically took a decades-old “health food” trend and made it groovy, shaggy, and redolent of nutritional yeast. The second became known as “California cuisine,” which was built on applying French and Italian culinary traditions to ingredients from the state’s budding assortment of small organic farms.

Back in April at the Bay Area Book Festival, I interviewed two food luminaries about the history of these starkly different movements: Alice Waters, author of the recent memoir Coming to My Senses: The Making of a Counterculture Cook, and Jonathan Kauffman, a food columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle and author of Hippie Food: How Back-to-the-Landers, Longhairs, and Revolutionaries Changed the Way We Eat.

As a Berkeley student active in the anti-Vietnam War movement that engulfed the campus in the ’60s, Waters had contact with the hippies but never become one. Instead, she had a culinary awakening in the French countryside while on hiatus from protesting—and this ultimately led her to launch Chez Panisse, arguably the most influential US restaurant over the past half century.

“I didn’t want anything to do with the hippies’ style of health-food cooking,” she writes in her memoir. “To me, that world was all about stale, dry brown bread and an indiscriminate way of eating cross-legged on couches or on the ground with none of the formality of the table…I thought their approach was absolutely uncivilized, unrefined.”

I got Waters to talk more trash about hippie food and the “brown bread” of the time. And Kauffman recounted the exploits of “Gypsy Boots,” a man who emerged as the most well-known and charismatic proponent of hippie food in the ’60s.

But towards the end of our conversation, Waters revealed that she has come to embrace certain forms of hippie food—even whole wheat bread. She cited a diagnoses of high cholesterol, and the advice of friends that she should stick to whole grains. After years of disdaining the stuff, she worked with local wheat farmers and a baker to produce a whole wheat loaf that actually tastes good. She’s even working on making the Chez Panisse prix fixe dinner fully vegetarian one night per week.

I asked Waters for a recipe that exemplified her early approach at Chez Panisse, and she delivered the secrets to her most iconic dish. From Kauffman, I asked for a recipe for modern hippie food that “doesn’t suck,” and he came by with a great guide to making grain bowls at home.

Baked Goat Cheese with Mesclun Salad

By Alice Waters

Serves 4

½ pound fresh goat cheese (one 2 by 5-inch log)

1 cup extra-virgin olive oil

3-4 sprigs fresh thyme, chopped

1 small sprig rosemary, chopped

½ sour baguette, preferably a day old

1 tablespoon red wine vinegar

1 teaspoon sherry vinegar

Salt and pepper

¼ cup extra-virgin olive oil

½ pound Mesclun lettuces, washed and dried

Carefully slice the goat cheese into 8 disks about ½ inch thick. Pour the olive oil over the disks and sprinkle with the chopped herbs. Cover and store in a cool place for several hours or up to a week.

Preheat the oven to 300F. Cut the baguette in half and leave it in the oven for 20 minutes or so, until dry and lightly colored. Grate into fine crumbs on a box grater or in a food processor.

Preheat the oven to 400F. (You can also use a toaster oven.) Remove the cheese disks from the marinade and roll them in the bread crumbs, coating them thoroughly. Place the cheeses on a small baking sheet and bake for about 6 minutes, until the cheese is warm and the breadcrumbs are brown.

Measure the vinegars into a small bowl and add a big pinch of salt. Whisk in the oil and a little freshly ground pepper. Taste for seasoning and adjust. Toss the lettuces lightly with the vinaigrette and arrange on salad plates. With a spatula, carefully place 2 disks of the backed cheese on each plate and serve.

Grain Bowls with Herb Sauce

By Jonathan Kauffman

“I love a grain bowl covered with a mix of fresh and leftover vegetables. Freekeh is a favorite base—for its slightly smoky note—or quinoa cooked with one of those higher-end vegetable bouillon cubes to double up its umami. A grain bowl that looks like the ones at Sweetgreen can take a ridiculous amount of time if you’re cooking every component that night, so I’ll cook up a cup of grains on Sunday while I’m already in the kitchen cooking and stick them in the fridge for a weeknight dinner.

For the toppings, I’ll use roasted carrots or sweet potatoes, which I always seem to have on hand because I can’t get enough of them, and quickly blanch a tangle of chard, beet greens, or turnip greens snipped off the root vegetables I’ve bought at the market. Because I am in California, an avocado is usually called for, and because frying an egg is quick work, one of those, too. I never stint on salt, because vegetables and grains without enough salt are dreary.

But the main difference between the macrobiotic plates of 1970 and 2018 grain bowls I actually want to eat is a flavorful sauce. After years of buying bunches of herbs for recipes and later throwing away a clutch of slimy, brown and expensive leaves, I’ve been inspired by Anna Jones (A Modern Way to Cook) to turn all my leftovers into herb smash: In a bullet blender I whiz together a mix of soft herbs (a combination that can include parsley, cilantro, basil, tarragon, dill, mint) with garlic, oil and lemon juice, then quickly throw the pesto in the freezer to retain its color. I have several in there at any one time. I pull out a jar, defrost it, and spoon it over the grain bowl, sometimes mixing it with Greek yogurt if the pesto’s flavor is too pungent on its own.”