On her phone, Crystal Rodriguez keeps a photo of her father hooked up to a ventilator. Nurses at the hospital sent her the image after he’d spent close to a month in the intensive care unit at UCHealth Medical Center of the Rockies in Loveland, Colorado, battling severe complications from COVID-19. At 58, he was unable to speak or visit with family. Rodriguez is convinced that her father was exposed to the coronavirus at work on the meatpacking line at JBS, a Brazilian-owned multinational that brings in $50 billion annually as the world’s largest meat processor. “They have so much money and so much knowledge of everything,” Rodriguez says. “Why didn’t they help protect us?”

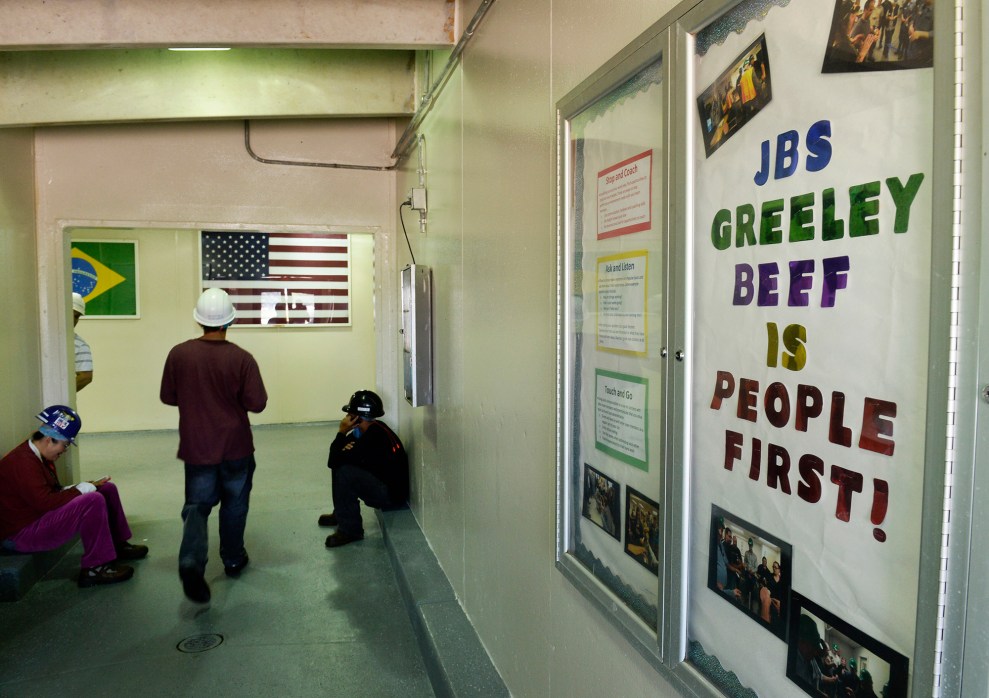

A 33-year-old single mother of four, Rodriguez grew up in Greeley, Colorado, home to JBS’s American headquarters and a massive plant that employs 6,000 workers. Rodriguez has worked there, on and off, alongside her father since she was 18. In the photo on her company ID, she has thick black hair and a wide smile, but her happy expression belies the reality at work. She says JBS is like a bad ex-boyfriend who you keep trying to leave, “but you still go back for some reason.”

Courtesy Crystal Rodriguez

Every workday in Greeley, plant employees herd 5,000 cattle onto the kill floor, where more workers stun, bleed out, dehide, dehair, gut, and split the carcasses. The hanging halves are chilled and aged, before a line of still more workers, standing along a snaking conveyor system, butchers each into individual cuts for packaging. For eight hours each shift, Rodriguez stands elbow to elbow with a dozen other employees, pulling slabs of beef off a conveyor belt and swiftly trimming them into cuts of lean brisket. The work is taxing, and the repetitive, forceful motion takes a toll. Rodriguez says her hands tingle at night, and her fingers are curled and misshapen from holding a knife and hook all day. She calls them her “grandma hands.”

Her latest stint at JBS began in August of last year. She says the money was decent, and she could share lunch breaks with her dad, who had spent the last 40 years working there. Sergio Rodriguez took a job at JBS at the age of 18, shortly after arriving in the US from Durango, Mexico. In doing so, he joined the legions of new arrivals, immigrants from Latin America and later refugees from countries like Somalia and Myanmar, who today make up half of the workforce at all of America’s meatpacking plants. Roughly half of those immigrants are undocumented. Often with limited English skills—at the Greeley plant alone there are roughly 30 languages spoken at any one time—they find themselves relegated to one of the most dangerous jobs in the country.

Still, Rodriguez says her father raised her and her siblings on his JBS wages. For years he worked in fabrication, shearing away meat from the ribs and spine, until he sustained a work-related hand injury and was reduced to “light duty” in the laundry department, passing out gloves to the other workers. Growing up, Rodriguez remembers he’d warn her and her siblings to stay in school. He didn’t want them to work at JBS. “They treat you like you’re nothing, like you’re an animal,” he’d tell them.

By mid-March, Rodriguez says she started noticing co-workers missing from the line. The parking lot seemed emptier than usual. According to data from the county health department, COVID-19 had already begun spreading among workers at the plant. Yet even as Colorado schools were ordered to close and the country declared a national emergency, the production line at JBS continued to run as usual.

On March 20, Rodriguez showed up for her shift at 5:45 a.m. and later that day shared lunch with her dad. As she left that afternoon, her mom called to say her dad had come home sick and gone to urgent care with a high temperature. Doctors said his symptoms were consistent with COVID-19 and advised him and the rest of the family to self-quarantine. Rodriguez says she called her supervisor to report that she’d likely been exposed. “They said, ‘But you’re not symptomatic, so you should come to work.’” If she wanted to take two weeks off to quarantine, Rodriguez says, she was told she would lose her job and would have to reapply after 90 days. “No one is forced to come to work and no one is punished for being absent for health reasons,” a JBS spokesperson said in an emailed statement. “If anyone experienced something different, that is troubling and not consistent with our culture or our policies.”

A week after visiting urgent care, Rodriguez’s father was admitted to the hospital, where he tested positive for the virus and was placed in the ICU on a ventilator. Days later, news hit the local press: The JBS plant was in the grip of a full-blown outbreak. Since then, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment has found that more than 245 workers have tested positive, and six have died. But the company has refused to offer tests of its line workers, and it reopened earlier this week—barely halfway through a two-week quarantine mandated by the health department. On Tuesday, President Trump issued an executive order to classify meatpacking plants as critical under the Defense Production Act, meaning that plants would be required to remain open. “We thank the Administration for acknowledging the important role food companies serve and ensuring that our food supply will remain resilient during these unprecedented times,” JBS wrote in a statement praising the move.

Workers fear that JBS is signaling that it intends to use the White House order as cover to continue production, even as advocates argue that protections for workers are insufficient. “All these years that my dad has given them,” Rodriguez says. “This is how they’re going to show they care?”

In rural America, especially in the Midwest and Great Plains, meatpacking plants have emerged as the most significant COVID-19 hot spots. More than 1,000 cases have been linked to a single Smithfield pork packing plant in Sioux Falls, South Dakota—over half of all cases in the entire state. The situation in Sioux Falls was so localized and severe that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention deployed an investigation team to assess work conditions at Smithfield. The agency used the case study to develop guidelines for slowing the spread, unveiled by Republican Gov. Kristi Noem at a press conference on April 20. The changes seemed modest: improved social distancing, use of face shields and other protective equipment, and better lines of communication with workers and their families. “There’s nothing in this report that I think will be difficult to accomplish,” Noem said. Still, the interim guidance, issued jointly by the CDC and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, is entirely voluntary and explicitly allows asymptomatic workers who have been exposed to COVID-19 to remain on the line.

“These were already workplaces with impossibly high injury rates for people in close-quarter work with cut injuries and crippling injuries from the high speed of work,” says Darcy Tromanhauser of Nebraska Appleseed, a nonprofit that does immigrant advocacy work in dozens of meatpacking towns. “Now, there’s this new layer of risk to life.” In recent years, meatpackers have pushed for loosening of government oversight to allow production lines to move faster, yielding more meat and greater profits with less inspection by the Department of Agriculture and less oversight of work conditions by OSHA. Nebraska Appleseed and other advocacy groups and local unions have long pushed for improved worker safety measures in packing plants, and they were some of the first, nearly two months ago, to call for new PPE and improved work protocols amid the pandemic.

JBS employees at the Greeley plant interviewed for this story report that there was talk of installing protective plexiglass shields between workstations, but they were only erected in the break room a week before the plant closure. Workers were not issued face masks, much less face shields, according to a letter sent from a local union to Colorado Gov. Jared Polis on April 11. (JBS acknowledges that it did not provide workers with masks until “early April.”) Health information posted around the plant was written only in English, and some report that, as concerns grew about preventing spread, they were left without basic sanitary supplies. “People don’t have the soap they need to wash their hands after they go to the bathroom,” Crystal Rodriguez said of the Greeley plant. “People just have to wash their hands with pure water.”

All of the workers we interviewed said they had been hearing rumors about co-workers testing positive for the coronavirus for more than a month before it finally hit local news, but plant supervisors weren’t sharing that information. Instead, line workers say they were repeatedly pressured to just keep working, even if they were feeling ill or had been exposed to people who were.

A JBS spokesperson said “if someone is sick or lives with someone who is sick, we send them home,” and that the company has protocols in place for quarantining people who have potentially been exposed to COVID-19. The spokesperson said the company’s high-risk workers (those older than 60, pregnant, battling cancer, or on dialysis) are receiving full pay and benefits while quarantining at home. Any worker who does not qualify as high-risk, but who is concerned about COVID-19, “can choose to self-quarantine and take unpaid leave.”

Andy Cross/The Denver Post/Getty

Before the pandemic hit, plants like JBS already struggled to keep enough workers on their production lines. The industry has acknowledged a labor shortage, thanks to previously low unemployment rates and policies enacted under the Trump administration that limit the number of refugees into the country. The Greeley plant had enough workers to run at full capacity, “but it wasn’t like they had a reserve of workers,” said Kim Cordova, president of United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 7. Internally, industry executives, managers, and sales representatives have been warning restaurants and grocery stores that even temporary plant closures would cause disruptions in getting fresh meat to market. Meanwhile, wholesale beef prices have risen so sharply that the USDA on April 8 promised to widen an existing investigation into the possibility that JBS and other meatpackers have engaged in collusion and price fixing.

JBS has declined to comment on these allegations, but other industry leaders insist that climbing prices are simple supply and demand. As capacity to slaughter and butcher cattle and hogs has dropped by more than 20 percent since early April, prices have started to climb as experts warned of a coming meat shortage. “The food supply chain is breaking,” John H. Tyson, chairman of Tyson Foods’ board of directors, wrote in a full-page ad that ran in the Sunday edition of the New York Times on April 26. “We have a responsibility to feed our country. It is as essential as healthcare.”

JBS was made aware of the first positive case among its Greeley workers as early as March 26. That day, the company gave employees 5 pounds of ground beef as a thank you for coming to work, and the plant continued to operate as normal. As more workers, including Crystal Rodriguez’s father, were hospitalized and tested positive, fear began to spread. On Monday, March 30, more than 800 employees walked off the job at the plant in Greeley. According to the UFCW Local 7, the mass no-show was likely prompted by panic among workers after JBS disclosed internally that it had 10 positive coronavirus cases. But the next morning, the plant once again opened as usual, and JBS still had made no public acknowledgment of its cases.

That same day, March 31, Cuyler Meade, a reporter with the Greeley Tribune, received an anonymous tip in his inbox. The sender never explained their connection to JBS but claimed that several workers at the plant had tested positive for COVID-19, and now four were hospitalized. Meade ran a story about the walkout, and the messages from workers began spilling in. “All of a sudden, it’s just a flood of people coming forward saying it’s really bad,” he said, “and these are the things they’re doing wrong.” Through anonymous and on-the-record sources, Meade was able to report on Beatriz Rangel, the daughter of longtime JBS worker Saul Sanchez. Rangel had tried desperately to inform supervisors that her father had tested positive for the virus. Another source described how a different JBS employee had failed to receive the regular wages he’d been promised as he fought for his life on a ventilator. Meade credits Rangel’s willingness to speak on the record with helping to “break open the usually impenetrable concrete walls of the beef plant during a critical time.”

Even as news reports of new cases and deaths continue by the hour, many workers still feel afraid to speak out. Saul Sanchez and his daughter had US citizenship, giving them some security to answer questions from the press. But those working without legal status, who account for an estimated quarter of meatpacking workers in America, do not feel so empowered. They are particularly worried now, as Trump-era crackdowns mean that publicly raising concerns about workplace safety might not only mean losing their jobs but facing immigration raids and deportation. Several workers at JBS expressed grave concerns about the workplace but declined to be fully interviewed for this story, citing the possibility of consequences at work.

By the time Meade’s story ran, a team of local epidemiologists from the Weld County Department of Public Health and Environment had already begun interviewing employees in private. Data collected directly and from local health care providers found that 194 workers or their family members had visited an emergency room or clinic for “respiratory illness suspected or confirmed for COVID-19” between March 1 and April 2. Dr. Mark Wallace, head of that team, ordered immediate changes to workspaces and use of personal protective equipment for all employees. In a letter sent to JBS, Wallace emphasized that investigators had been told by workers that their supervisors were not taking steps to stop the spread of the virus. “These concerns expressed to clinicians included a perception by employees of a ‘work while sick’ culture,” he wrote. “If I find evidence of continued violations,” he concluded, “I will seek assistance from the District Attorney to consider criminal actions against you.”

Still, the line continued to run. And workers began to die. Saul Sanchez was the first. An employee at JBS for more than 30 years, rising to become a “green hat” supervisor, Sanchez was 78 years old. In one of his last conversations with his daughter, calling from the ICU at Greeley’s North Colorado Medical Center, he promised that he would be out of bed and back to work at the plant within the week.

Sanchez’s death stunned the community. Cuyler Meade wrote another story about Sanchez’s funeral, accompanied by painful images of his family gathered graveside, almost all of them wearing face masks, many of them with surgical gloves. Against doctors’ recommendations, his wife, children, and more than a dozen grandchildren embraced and consoled each other, as Sanchez’s casket was lowered.

And still, the line continued to run.

Alex McIntyre/The Greeley Tribune/AP

By the time JBS received Dr. Wallace’s letter on April 4, the company already had a widening problem among several other meat plants. Days earlier, JBS spokesperson Cameron Bruett announced that its beef plant in Souderton, Pennsylvania, had “temporarily reduced production because several senior management team members have displayed flu-like symptoms.” On April 3, Teresa Anderson, director for the Central District Health Department, which covers three counties in Nebraska, announced that the JBS plant in Grand Island had 10 new cases. At an online news briefing, Grand Island Mayor Roger Steele told reporters that he had been in touch with staffers for Republican Gov. Pete Ricketts and management at JBS. After those conversations, he had decided to allow JBS to operate as normal. “As mayor, I must balance the need for critical infrastructure, such as food processing and agriculture,” Steele said, “against the need for all of us…to practice social distancing and stay home when possible.”

JBS began vigorously disinfecting all surfaces and equipment with bleach. When Ana, a worker at the Grand Island plant whose identity we have agreed to protect by using a different name, started suffering severe headaches, she initially assumed they were caused by all the chlorine in the air. But then she heard other workers say someone had fainted on the production line and they were told to leave because they were possibly infected. Frightened, Ana left work. In her first few days off, her headache persisted. She developed a fever, a cough, and body aches. Meanwhile, she said, her supervisor continued to call, asking if she could come in for her shifts. Ana had to speak with a doctor about her symptoms before she could be placed on a waiting list to be swabbed. More than a week after she had left work on April 1, she tested positive for COVID-19.

In retrospect, Ana says she’s not surprised that she fell ill. As news stories of the virus’s rapid spread made national news, Ana says JBS took inadequate precautions to prevent spread within the plant. No one took their temperatures as they entered for shifts, she says, and efforts to promote social distancing in the break room didn’t begin until mid-April. When hand sanitizer ran out, it would be days before anyone refilled it. The bathrooms had no soap, and the hot water was shut off. Ana works on the production line in a refrigerated room, where temperatures are often just above freezing. “There’s a lot of people who preferred not to wash their hands when there wasn’t hot water,” she said in Spanish. (The JBS spokesperson stated that its plants “have plenty of available personal hygiene products.”)

Now, Ana, who is in her 30s and originally from El Salvador, says she’s recuperating but that she likely spread the virus to her mother and her husband, who have both tested positive. The family lives paycheck to paycheck, and no one is currently able to work. Like many JBS workers interviewed for this story, she is unsure if her employer plans on paying her for the time she’s been in self-quarantine. In the meantime, Ana says she’s rationing the family’s supply of food, including 10 pounds of hamburger presented by JBS to every Grand Island employee who continued to work amid the outbreak. During the day, she and her husband remain shut inside their bedroom, hoping to shield their four young children from the virus.

JBS has announced implementation of new safety measures in the Grand Island plant, including taking workers’ temperatures as they enter, installing plexiglass dividers between workstations on the production line, and “offering access” to face masks to each employee. (On April 19, the UFCW also announced it had negotiated a $4-per-hour pay increase for workers.) This past Monday, representatives from the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Global Center for Health Security inspected and approved the plant’s new safety protocols, but the steps may be too little too late. The Central District Health Department has now connected 237 cases of COVID-19 directly to the Grand Island plant, and Hall County, where the plant resides, accounts for nearly 40 percent of cases in the state of Nebraska.

Still, the line continues to run. On Friday, Gov. Ricketts was asked at a news conference what it would take for him to order closures of plants with outbreaks. “I don’t see a scenario to close them,” he answered. “You want to talk about some of these protests going on right now? Think about how mad people were when they couldn’t get paper products. Think about if they couldn’t get food.” Ricketts cautioned that if he tried to close meatpacking plants, “we would have civil unrest.”

Ana says she has no choice but to return to work when she can, but she dreads going back. Like many workers interviewed for this story at plants in Colorado and Nebraska, she says her trust in management has been shaken. Another worker, interviewed by Nebraska Appleseed, reported that supervisors at the Grand Island plant “are telling people that even if they are positive they can go to work, to keep it on the [down low]. And to not say anything or they will get fired.” JBS disputes this claim. “Under testing protocols,” a spokesperson said, “if a team member tests positive, they are quarantined.” But Ana says that whenever she asked if any of her co-workers had tested positive, her supervisors responded the same way. “They always denied it and said to not talk about things that we didn’t understand.”

On April 10, two more JBS employees in Greeley died. Tiburcio Rivera López, 69, had been quarantining at home, so official results would have to wait several days to confirm that his death was due to COVID-19. Family members said Rivera was always the last to arrive to any party and always entered carrying a case of Pepsi and a tres leches cake. “I just hope JBS can do something for his family,” a friend told Fox 31 in Denver. “He is the most humble person I’ve ever met in my life. Always smiling.” The family of Eduardo Conchas de la Cruz, 60, posted a GoFundMe page, explaining that he had been taken by ambulance to the hospital on April 2 with respiratory distress, heart failure, and kidney failure. Two days later, he was officially diagnosed with the virus and placed on dialysis. He never improved. The family’s GoFundMe request was for help covering his medical bills and funeral expenses.

That same day, JBS was given an order from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to close the doors of the Greeley plant immediately for two weeks. To reopen, JBS would have to implement several measures, including providing PPE and hand-washing to all employees, establishing social distancing within the plant, and, most importantly, testing all employees and performing contact tracing. At a White House press briefing, Vice President Mike Pence acknowledged the scale of the problem in Greeley and the challenge of testing thousands of employees, but he promised to directly coordinate the effort. “Our team is working with the governor to ensure that we flow testing resources,” Pence said.

JBS officials claimed they were already planning to take these steps and announced they would use Easter weekend to clean the plant. But on the following Monday, April 13, JBS said it would not test workers after all and instead would have them self-quarantine at home. Reporting by the ABC affiliate in Denver suggested that the reversal came after JBS began swabbing supervisors and found more than 40 percent were positive for COVID-19. JBS did not directly comment on that report. “We believe shutting down the facility was the most effective way to contribute to public health,” a company spokesperson wrote. “Testing does not stop the virus and only provides a one-time snapshot of infection.” Kim Cordova, president of UFCW Local 7, doesn’t accept that explanation. “I believe once it became apparent that many people were testing positive, they just stopped testing,” she said. “They don’t want the world to know how many people are sick in that plant.”

In the meantime, employees continued working until the morning of April 16, processing animals that had already been delivered from feedyards and awaited slaughter in their stock pens, and then reopened the kill floor on the morning of April 24—well short of the two-week closure and quarantine mandated by the Department of Public Health. On Monday of this week, all workers without symptoms were ordered back to the line. A JBS spokesperson said the company “implemented guidance” from the health department and other governmental agencies before reopening.

Andy Cross/The Denver Post/Getty

Those who have returned talk about improved conditions, including temperature monitoring before each shift and staggered lunch breaks, but there’s a looming fear that the virus is still spreading silently among the workforce. The company still hasn’t implemented all-employee testing and contact tracing or provided sequestration housing for sick workers, two strategies that the health department deemed necessary before the plant should reopen. Yet the Republican-controlled board of Weld County Commissioners is not only allowing JBS to remain open but encouraging all businesses in Greeley to reopen this week. “Opening too soon or without a staged plan,” leaders of local hospitals wrote in a letter to the commissioners, “[will] lead to widespread, severe illness that our health care system cannot handle. The resulting deaths will be tragic.” It remains unclear whether Democratic Gov. Jared Polis intends to intervene by ordering local businesses to remain closed.

Union president Kim Cordova has said she doesn’t believe it’s safe for her members or other meatpackers to return to work, calling the reopening of the JBS plant in Greeley “reckless and irresponsible.” She told ABC in Denver on April 22, “I think the workers are being sacrificed. I think that this could potentially be a death sentence.” The next day, she received a cease-and-desist letter from JBS saying that the union had violated its collective bargaining agreement when she suggested workers were at risk if they returned to their jobs on the plant floor. The company accused Cordova of attempting to “extort additional benefits” from JBS in the form of “specific safety protocols and health measures.” Matthew J. Lovell, JBS USA’s head of Labor Relations, Health, and Safety, wrote, “Not only have you conceded your intent to create negative publicity for the Company in an effort to force it to conform to the Local’s demands, but you are apparently proud of your flagrant disregard for the Local’s obligations under the [collective bargaining agreement].”

“The JBS plant is not a feudal fiefdom, which operates at the whim of its management nobility,” Cordova wrote in response. “It can, and should, be regulated by the appropriate health and safety agencies which exist to protect the public and workers at the plant.”

It’s not just JBS. In the course of reporting this story, we spoke to workers at Tyson Foods and Smithfield, as well as advocates representing workers at Hormel, Cargill, and dozens of regional packinghouses, who all reported similar conditions at other plants. In documents shared with us, Tyson Foods management, for example, promised to place dividers between employees on the processing line, even if that would mean slowing production. “The installation of dividers and barriers on the production floor and break rooms began in March,” Tyson spokesperson Gary Mickelson wrote in a statement. “The specific dates would vary by site.”

However, recent photos taken from inside a Nebraska Tyson plant, shared by a worker who asked to remain anonymous, revealed that as recently as April 16 there were still no barriers, and workers could be clearly seen working elbow to elbow. Despite commitments to run lines slower if necessary, earlier this month Tyson was granted waivers by the USDA to run lines faster in six of its plants. (Tyson says that all of the requests were submitted in February or earlier and were “appropriately made following the USDA process.”) Since the start of the pandemic, Tyson has closed plants in Iowa, Indiana, Kentucky, Washington, and, as of this week, Dakota City, Nebraska—after reportedly 669 workers in that location tested positive for the virus.

Andy Cross/The Denver Post/Getty

And like the workers at JBS, the employees of these other companies are often afraid to speak out. “They feel like they don’t have a voice,” said Daniela, a 23-year-old in Lincoln, Nebraska, whose father works in a Tyson packing plant and is a US citizen but still worries about retribution. The reluctance of workers to speak out, she says, combined with business-friendly politicians at all levels of government—as well as overwhelmed and cash-strapped advocacy organizations, and local media with dwindling resources and few reporters who speak Spanish—has created a culture of silence. Daniela believes that this not only permits worker mistreatment in the first place but also allows meatpackers to make promises to institute new safety measures without fear of follow-up from either politicians or the press. As a result, says Daniela, who asked that we not use her real name, Tyson has only installed barriers in the lunchroom. “They don’t want to do the extra work to put them in the work stations,” she said. “The regulation is to be six feet away from other people, and that is not what’s happening.”

Gloria Sarmiento of Nebraska Appleseed said she hears similar complaints from workers across the state. “They say the company is trying to improve conditions in the lunchroom or taking temperatures at the entrance, but inside, we are working elbow to elbow.” Without federal mandates—and even the recent guidelines from the CDC and OSHA being offered as a voluntary set of suggestions—the protection of workers has been uneven at best, and in some plants, adjustments to prevent the virus’s spread have been virtually nonexistent.

Even in plants where plastic or metal guards have been installed between workstations on the line, including the JBS plant in Greeley, experts worry they will have little effect in close quarters. “I’m not convinced they’ll do a lot to minimize spread,” said Tara C. Smith, an epidemiologist and a professor at the Kent State University College of Public Health, “especially since the employees are still standing very close and still may not have adequate PPE.” She said it’s hard to see how meatpacking work can be done safely without slowing the line and spreading out the workers. “They’re just too crowded,” she said, and laments that this problem hadn’t been tackled earlier. “It shouldn’t take deaths and a pandemic for us to realize how important these workers are.”

Araceli Calderon, who works with Centennial BOCES, a Greeley-based nonprofit providing agricultural workers and their families with education resources, agrees. “These are the poorest of the poor, and they’re just thankful to have work—however that doesn’t mean we can forget about them.” It is not lost on Calderon how quickly the hateful rhetoric from people across the country surrounding immigrants and refugees suddenly turned into declarations about how they are “heroes” and “essential” workers. Many people don’t seem to realize that being declared “essential” during the pandemic carries few benefits for workers; instead, it allows employers to impose greater work requirements with fewer restrictions. Calderon urged all Americans to consider citizenship protections to eliminate the current policy Catch-22 that has created a workforce largely made up of people who aren’t legally allowed to work and also, now, not permitted to stop.

“This is the moment that everybody needs to see individual faces,” says Calderon. “We need to look back and say, ‘Thanks to these people, I have food.’”

Nearly a month after being admitted to the hospital, Sergio Rodriguez has started toward a slow recovery. A few days after he was removed from the ventilator, he was discharged to continue recuperating at home. In a photo, the Rodriguez family stands outside UCHealth in Loveland, Colorado, surrounding Mr. Rodriguez, who is seated in a wheelchair and wearing a face mask. Ever since Crystal Rodriguez can remember, her dad has had the tendency to hide any physical pain or ailment, but now his muscles have atrophied so much that he requires assistance to shower and get around the house. His lungs are so battered that he struggles to talk without becoming winded. When her dad came home, he was still testing positive for the virus, but Crystal vowed this time that wouldn’t keep her at a distance of six feet. “I regretted that once he got put in the hospital, I couldn’t see him and I was going crazy,” she recalled. Now they hug in face masks and gloves.

Crystal says she’s done with JBS—with “the bad ex-boyfriend.” She says she’s never going back. But her father, despite having nearly lost his life, has told his family he would like to return to work at the plant. He’s near retirement and would like to finish out his career, if he is ever well enough to do so. Crystal says that growing up in Mexico he never had the chance to get an education. For people like him, she says, “that’s all they know: hard work.” He remains loyal to JBS, even as the consequences of the company’s refusal to test workers continue to reverberate.

Three more JBS workers in Greeley have died from COVID-19 in recent weeks. On Saturday, Crystal herself tested positive for the virus. Just a few days later, President Trump signed the executive order to keep meatpacking plants open to “ensure the continued supply of beef, pork, and poultry to the American people.” The line will continue to run.

This story was produced in partnership with the Food & Environment Reporting Network, a nonprofit news organization.

Top image: Alex McIntyre/The Greeley Tribune/AP