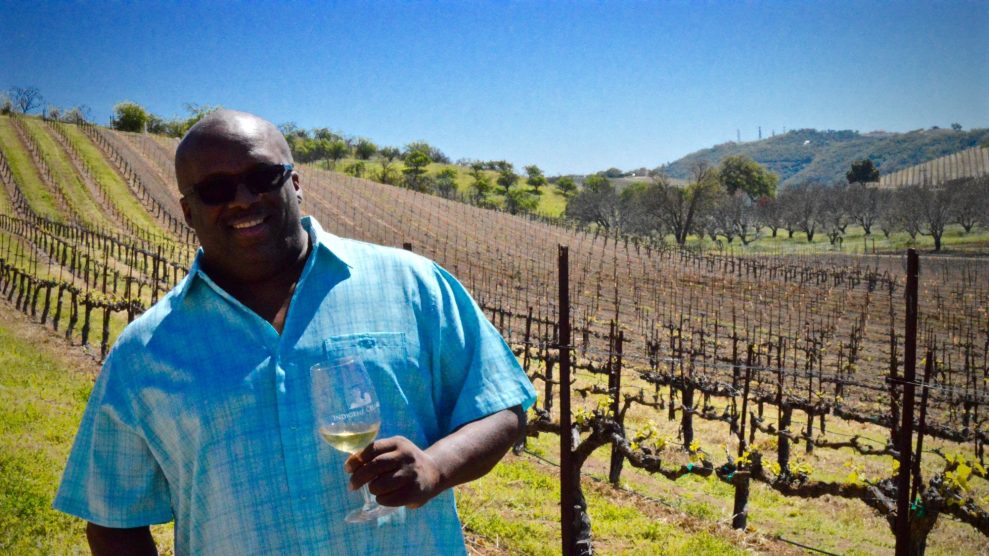

Xavier Morgan, who joined the FFA chapter at his Chicago high school, recently moved to San Diego for work. He has been advocating for racial equity in the organization, which is predominantly white.Peggy Peattie./FERN

This story was originally published by Food and Environment Reporting Network.

When Xavier Morgan first enrolled in the Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences in 2010, he wasn’t necessarily interested in farming. In fact, his admission to the school, which his aunt recommended due to its strong reputation for career and technical education, was in part a product of chance.

“I actually have no family ties to agriculture whatsoever,” says Morgan, who grew up in Chicago. “We went one day, took an application, and then I got in.”

By his sophomore year, Morgan found himself involved with the school’s chapter of the National FFA Organization, formerly known as Future Farmers of America. He was first drawn to the organization—the largest student-led farm group in the country, with 600 members at his school—for its leadership opportunities. But soon he came to have a passion for agriculture, eager to shape the future of an industry that he now considers “the most important in the world.” He began to rise through the group’s leadership ranks.

In his diverse community of peers and teachers, Morgan felt supported as a Black man embarking on a career in agriculture. Yet he had an unnerving experience when, in 2011, he attended his first national FFA convention. He was struck by the homogeneity of the crowd. Flanked by many friends of color from his local FFA chapter, he wasn’t used to being in a room filled with aspiring white farmers.

“I remember walking in and eyes turning,” he says. “It was a shock walking into that convention and not really seeing that diversity that we have at our chapter.”

Outside of rural and farming communities, FFA is generally not well known. Yet the $31 million organization has over 700,000 members in all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. It boasts over 8 million alumni who work in all levels of the agricultural industry—from farms to equipment dealers to the biggest food and agrochemical companies. It writes agriculture curriculums that are taught across the country.

Yet much like the agriculture industry, FFA is disproportionately white. According to a 2019 report, white members make up nearly 70 percent of the organization, while around 15 percent are Hispanic, and only four percent are Black. In fact, the percentage of Black members hasn’t budged since the early 1990s. This disparity is even starker for FFA’s adult advisers, who oversee the high school chapters and often serve as students’ introduction to the program. A study published in 2013 found that nearly 70 percent were white men.

According to interviews with several former and current FFA leaders and staff, and a review of academic research on the organization, FFA has tried repeatedly for years to expand its Black membership and diversify its leadership, but it has failed. Although it remains a highly influential educational and leadership development program for young people interested in the agriculture industry—with ties to federal agencies and the biggest agribusiness companies—it has disproportionately served white students.

Given the organization’s racial disparities and a general aversion to engaging with political issues, Morgan was surprised when scrolling through Facebook on May 31, he learned of FFA’s attempt to wade into the national discourse on race shortly after the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers. FFA had added its voice to the growing chorus of organizations releasing statements about their commitment to racial justice. Many of those organizational statements have been criticized for opportunism and platitudes. But Morgan found FFA’s post, which has since been deleted, particularly disturbing, taking an equivocating tone.

“In my opinion, it was insensitive to the current situation,” he says. “I was just like, they shouldn’t have even posted if they’re going to post something like this.”

He shared the post with a few friends. Later that day, he noticed something else. An FFA alumnus who had previously served as one of seven national officers—the organization’s highest rung of student leadership—had posted a video to her Instagram account calling on her followers to support the Black Lives Matter movement. In the comments, a 2020 national officer, Lyle Logemann, had left a long comment disparaging the video and calling it “nonsense.”

“Wouldn’t kill you to advocate for your own country once in a while,” he wrote. “If it’s so bad and primitive then buy yourself a one-way ticket to a country you think is better.”

Morgan says this rhetoric was painful to encounter coming from a prominent FFA leader. “Especially as a person of color, that’s one of the things that we hear all the time from people: ‘Go back to your country,’ or, ‘go back to wherever you came from,'” he says.

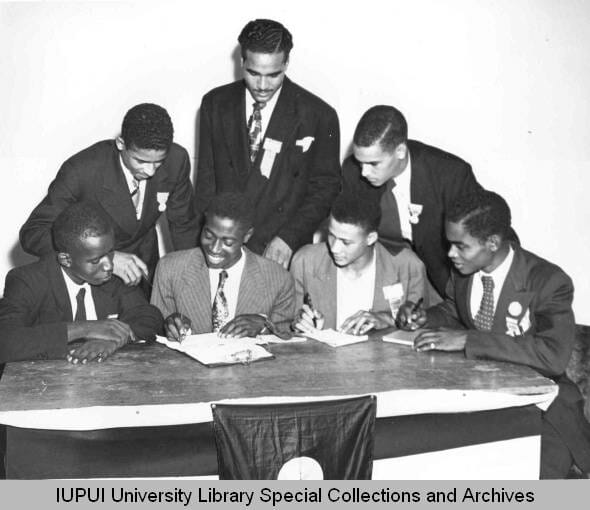

Xavier Morgan (top right) with the 2013-2014 Illinois Association FFA State Officer Team.

Xavier Morgan

Morgan and other FFA alumni began discussing what could be done and contacted the organization’s leadership to express concerns. At first, FFA planned to address the matter internally, says Mark Poeschl, FFA’s chief executive officer since 2016. He believed there was “an opportunity to provide some corrective instruction and to try to work with that individual to improve his sensitivity.”

But the next morning, Morgan received a more distressing message about Logemann. Another FFA member had discovered racist, xenophobic, and homophobic memes on Logemann’s Facebook account spanning from 2013 to 2019. Morgan decided to post the memes to his own Facebook page on June 3, along with a call to national FFA to take action. The post went viral. The next day, FFA announced that it was removing Logemann from his post as a national officer. Logemann has since been scraped from the website profiling current national officers, and apparently photoshopped out of the accompanying team picture.

Motivated by this quick response, nearly 400 FFA members, alumni, and former officers sent a letter to Poeschl demanding that the organization set concrete goals to enhance diversity and create a new staff position dedicated to that work. A petition with the same demands has garnered nearly 8,000 signatures. So far, the organization has committed to reviewing its national officer candidates’ social media as part of future vetting processes, but it has not yet responded to the entire list of demands.

Some FFA alumni and members have argued on social media that Logemann’s actions were one forgivable mistake amid years of good work, and disagree that the organization has failed to serve its members of color. A petition to reinstate Logemann has racked up nearly 3,300 signatures and a GoFundMe to replace the FFA scholarship he reportedly lost with his removal from office has raised over $4,000. (Poeschl declined to comment on the status of Logemann’s scholarship. On July 30, Logemann filed suit against FFA seeking damages for the loss of his scholarship and position.)

Logemann says the memes he posted were “certainly insensitive and not funny as I mistakenly perceived through the eyes of my 14- and 15-year-old self,” though he stands by his comment on the former FFA leader’s Instagram post, which he characterizes as “derogatory and divisive.” In his time at FFA, Logemann says he “never witnessed any racial minority being discriminated against.”

But many FFA members and alumni of color believe that removing Logemann was only the first step towards addressing the organization’s ongoing issues with racism. “The removal of Lyle, that was not our goal. That was only one of the things that we wanted to address,” says Morgan. “We want to change FFA for the better.”

FFA was founded in 1928 in Missouri as an agricultural training program for farm boys but has since evolved into a federally chartered program that develops high school curricula on agriculture, working closely with the Departments of Agriculture and Education. FFA members, ages 12 to 21, participate in local and national competitions, training sessions, mentoring, and conventions. Many assume leadership positions at the local, state, and national levels and remain passionately engaged in the organization after aging out of it.

FFA’s members and leaders stress that since its inception, it has expanded its education and training programs to encompass a wide range of fields beyond farming. But the organization is still closely tied to the agriculture industry. Its top sponsors include the biggest agribusiness companies, such as Bayer, CHS, John Deere, Corteva, Cargill, and Syngenta. Over 80 percent of its alumni go on to work in the sector, including Morgan, now 24, who manages the San Diego region for Hormel Foods’ food service division.

Until the mid-1960s, the vast majority of FFA’s members were white men—and the legacy of that era remains. Despite efforts to diversify the organization, nearly all of its leadership positions are held by white people. The organization’s executive management team, board of directors, board of trustees, individual giving council, alumni advisory committee, and foundation sponsors board—over 80 positions—are overwhelmingly white. Of national FFA’s 162 employees, 19 are people of color, and eight are Black, according to a spokesperson.

This disparity mirrors the US agriculture industry itself, where around 95 percent of farmers are white, while the agricultural workforce is overwhelmingly made up of people of color. Over the last century, the number of Black farmers has also collapsed from nearly 1 million in the 1920s, about 14 percent of the nation’s total, to around 45,000, or under 2 percent, today.

FFA says it serves a wide range of young people interested in agriculture and emphasizes that 18 percent of its chapters are located in cities or suburbs. But despite the organization’s geographic reach, alumni say its curricula and leadership program haven’t effectively addressed internal racial disparities. Morgan says he took diversity as a given when he was working in local leadership in Chicago. “But once I left my section and traveled for FFA,” he says, “I was quickly reminded.”

DeShawn Blanding also had his most eye-opening experiences with racism in the FFA community when he ventured away from home. In 2016, he took a year off from North Carolina A&T State University, a historically Black college, to serve as an FFA national vice president, one of the most prestigious student leadership roles in the organization. His role entailed visiting FFA chapters around the country, serving as a role model for younger students, and advocating for agricultural education. But many of those visits amounted to “a culture shock, to say the least,” he says. “I didn’t really see myself reflected in any chapters.”

Other Black former FFA leaders recounted racist experiences they had while traveling to all-white FFA chapters around the country. One recalled encountering a white student who admitted she had never spoken to a Black person before. Others said they were confronted with confederate flags. Another remembered a visit to Missouri where a white student told her she wouldn’t listen to her presentation because she was Black.

Blanding says that he wasn’t necessarily surprised to encounter racism among the hundreds of FFA members he met, given the history and make-up of the organization. After all, he says, “You can’t really expect the high school program to be diverse if the actual industry isn’t diverse. The organization was created for white farm boys.”

The racial disparities in FFA’s membership are an issue, says Poeschl, FFA’s CEO. But diversity is broader than race, he says, and includes gender, religion, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation. “We look at it as a whole broad picture of what we need to accomplish,” he says.

FFA, for example, has worked for decades to grow its roster of female members. Women weren’t allowed into the organization until 1969, and a woman wasn’t elected student president until 1982. Today, nearly half of FFA members are women.

But just 18 of the organization’s more than 80 non-student leadership positions are held by women. And it was not until 2017 that the organization marked two milestones: the election of its first and only Black woman student president, and the retirement of its antiquated gendered dress code, in which women were required to wear skirts for official FFA events. (Now, women may also wear slacks.)

The group has also advertised its support for queer students, but evidence of the organization’s progress on recruiting LGBTQ members is thin. An FFA spokesperson said that the organization does not collect data on the sexual orientation of its members or leadership. Several alumni interviewed for this story said they weren’t aware of an openly queer state or national FFA officer ever, and that homophobic experiences were common among queer members.

Morgan Rutar, a white FFA alumna from New Jersey, made her bisexual identity a significant part of her platform when she ran for a national officer position in 2017. But some of her FFA mentors advised her that being open about her identity would disadvantage her in the selection process, and she was not ultimately selected for the role. “To this day, I still wonder if [being bisexual] was a contributing factor,” she says.

Some alumni have been tapped by FFA to help address its lack of diversity. But they say those efforts, too, have fallen short.

After serving as national vice president, Blanding joined an FFA task force focused on diversity and inclusion in 2018. He says it was the organization’s third such task force, this one focused on diversifying the curricula taught in local FFA chapters. But, he says, the task force was led by white professional FFA staff and advisers who took input, but not direction, from FFA student leaders of color. Ultimately, the outcome was “a cosmetic solution,” he says.

“They have ideas,” he says of FFA leadership. “[But] because it’s led by the voices of those that are not marginalized, they don’t understand the depth of the problem.” Despite his disappointment in that process, he is still working with fellow alumni to reform the organization.

FFA alumni are quick to connect the contemporary work of diversifying the organization with the legacy of racism in agriculture, and particularly the steep decline in the number of Black farmers since the turn of the 20th century.

One event that contributed to that rapid decline lies in FFA’s history, when the organization took over its Black corollary, the New Farmers of America (NFA), in a merger forced by the US government in 1965. Many of the FFA members working today to push the organization forward on racial justice point to that merger, and their miseducation about it by the FFA curriculum, as a spark for their current activism.

New Farmers of America National Officers, 1947.

Indiana University

NFA was founded in Virginia by young, rural Black men and their advisors in the 1920s, around the same time as FFA. In the following decades, the organization grew to span 18 states, 1,000 chapters, and over 58,000 members. As in FFA, NFA members participated in rigorous agricultural education, leadership development, and livestock competitions.

When NFA was founded, FFA was technically open to all races. But because FFA was built around school-based chapters, Black students were functionally excluded from the organization during the era of legal school segregation. In the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision in 1954, federal officials became concerned about the existence of segregated agricultural education programs. Discussion began about merging two groups, with one official writing in 1963 that authorities as high as the White House were “[dissatisfied] with the progress that is being made [in integrating FFA].”

With the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, the federal government applied a heavier hand in ushering the two groups together, specifically by integrating NFA members into FFA. In September 1964, Francis Keppel, then commissioner of education—the predecessor to today’s secretary of education—wrote to the FFA national advisor expressing his concern. The rank-pulling and decade of pressure worked. By February 1965, FFA and NFA had agreed to a merger plan. NFA members joined FFA on July 1, 1965, and the NFA was dissolved.

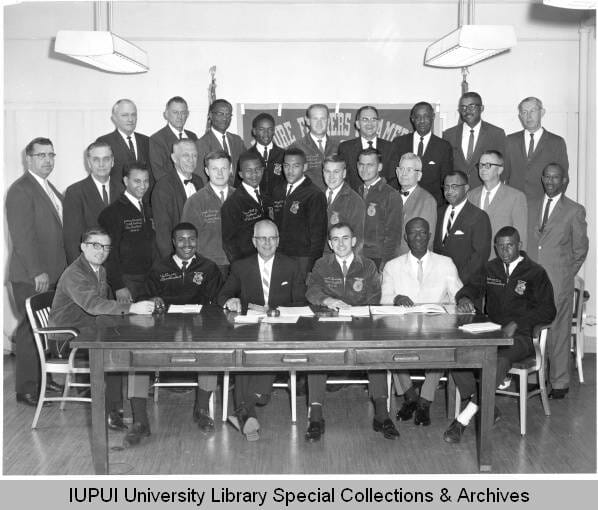

A joint meeting of the national student officers and administrative boards of the Future Farmers of America and the New Farmers of America in Washington, D.C., July 29, 1965.

Indiana University

Rather than creating a more diverse organization that could serve white and Black students alike, the merger actually reduced Black participation in agricultural education, and likely, professions. Following the takeover, Black members were not well represented in FFA leadership, which led to “poor morale and a loss of identity among Black students,” according to academic interviews with former FFA members. Where NFA’s Black agricultural educators had been deeply invested in their students, some of FFA’s teachers “certainly gave up on some of the African American kids,” one former member recounted.

The loss of NFA and the lack of support for Black students in FFA contributed to a steady decline in Black membership. Around 50,000 NFA members joined FFA, which at the time had over 450,000 members, in 1965; today, FFA has only about 30,000 Black members and a total membership exceeding 700,000.

Several FFA alumni say that they were misled by the organization about the merger, which is typically described in the FFA curriculum as a win-win scenario that enhanced the diversity of FFA and gave more opportunity to Black NFA members.

“We always talk about how it was so great that we merged [with NFA],” says Sean Harrington, a white FFA alumnus from Indiana. But when he recently learned more about the NFA’s history, he was “appalled.” He sees a connection between contemporary racism at FFA and the obfuscation of this racist chapter in the organization’s history. In May, he took to Twitter to express his frustration on the issue and to connect racism in agriculture to the contemporary uprisings for Black Lives Matter across the country.

Harrington soon connected with other FFA alumni who felt similarly frustrated. Within weeks, FFA’s clumsy statement on race and Logemann’s actions would engulf the national FFA community in a reckoning with institutional and systemic racism. Harrington, along with Morgan and a cohort of other FFA alumni, would soon be pushing the organization towards more dramatic change.

Today, a reckoning around racism and discrimination continues in the FFA community. On July 30, Logemann filed suit against the organization for breach of contract and is seeking damages due to the loss of the scholarship associated with his role. A letter sent from Logemann’s attorney on June 24 to top FFA leadership called Logemann’s removal “a betrayal,” and argued that FFA’s actions “[chose] cowardice to appease a mob to unfairly penalize a young man for posting distasteful memes as a teenager.”

Meanwhile, Morgan says that FFA has not completely addressed any of his and others’ demands. At times, he’s felt discouraged. “If they wanted to make it happen, they’d make it happen,” he says of FFA leadership. “I’m trying to remain positive, but it seems like some of the stuff they’ve told us seems like the runaround.”

Yet he is still working with Blanding, Harrison, Rutar, and other FFA alumni, including the organization’s first Black woman president, Breanna Holbert, who is also a member of the organization’s board of trustees, to hold the organization accountable to its stated commitments to diversity.

“There’s a lot more to address here in terms of Indigenous folks, the Latinx community,” says Holbert, who identifies as Latinx and Black. “National FFA uses a lot of Black students and people of color in their magazines but doesn’t really practice what it preaches.”

FFA’s progress on racial diversity is a crucial pillar to diversifying agriculture as a whole, the organizers say. Many of them currently work in the farm sector and related fields or want to pursue careers as agricultural educators. Agriculture, they say, must welcome people of all backgrounds.

“Agriculture seeps into every facet of Black Lives Matter,” says Blanding. “The movement is calling for the dismantling of systemic racism, and that goes into the racism inherent in the agriculture industry as well.”

Holbert says the industry faces an existential crisis if it doesn’t evolve and change. “If agriculture doesn’t step up,” she says, the field is “going to be left behind.”