Workers on the line at a Triumph Foods pork processing facility, April 28, 2017 in St. Joseph, Missouri.Preston Keres/Planet Pix via ZUMA Wire

A new bill, jointly released last week by Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), seeks to address an injustice laid bare by the coronavirus pandemic: the gaping power differential between the people who process the US meat supply and the executives and shareholders who profit from their labor. It would do so by protecting meatpacking workers from repetitive stress injuries, which have become endemic to the occupation. The legislation would also likely bolster worker safety during future viral outbreaks.

In an important sense, the COVID-19 era has been a tale of two pandemics: one for people whose jobs require them to toil indoors at close quarters, and another for those who can make a living without facing such hazards. Few industries sum up the situation more neatly than meatpacking. An October 27 report from the US House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis found that in plants run by the five biggest US meatpacking firms—JBS, Tyson, Smithfield, Cargill, and National Beef Packing Company—at least 59,000 workers tested positive for the virus during the first year of the pandemic, and at least 269 died. At several individual plants run by these multinational conglomerates, upward of 44 percent of the workforce tested positive in that period. “The full extent of coronavirus infections and deaths at these meatpacking companies was likely much worse than these figures suggest” because of incomplete data, the report added. It concluded:

Instead of addressing the clear indications that workers were contracting the coronavirus at alarming rates due to conditions in meatpacking facilities, meatpacking companies prioritized profits and production over worker safety, continuing to employ practices that led to crowded facilities in which the virus spread easily.

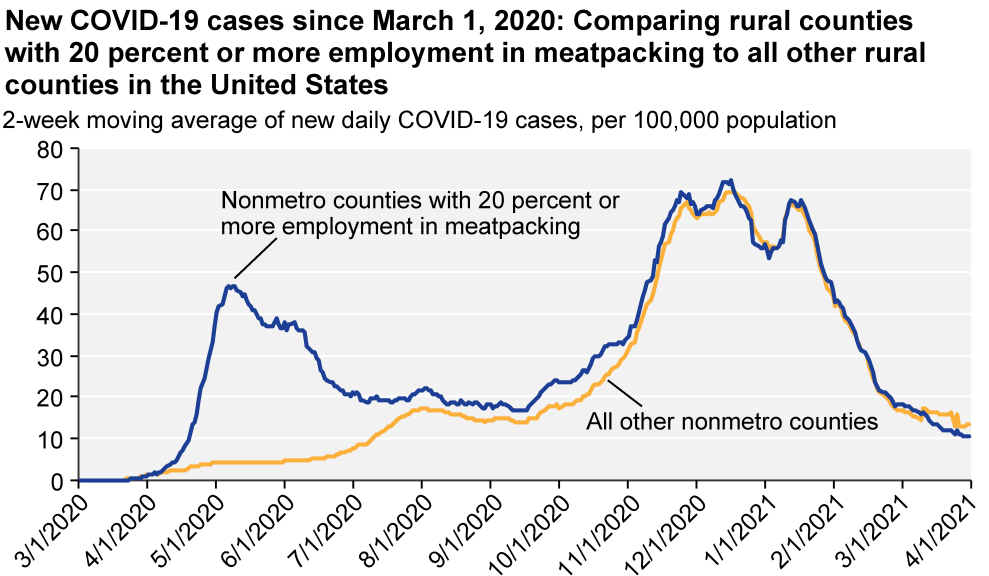

The outbreaks spilled out into surrounding communities as meatpacking plants emerged as prime vectors for spreading the virus into rural America. A May 2021 US Department of Agriculture report told the story in one grim chart, comparing COVID cases in meatpacking-intensive rural counties to their non-meatpacking-heavy peers.

Economic Research Service / US Department of Agriculture

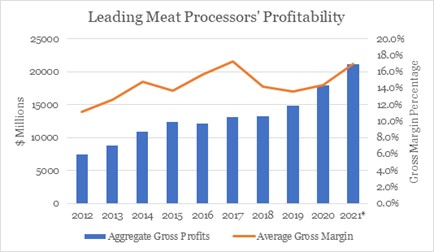

For the industry’s executives and shareholders, the crisis brought opportunity. The conglomerates that dominate the trade successfully lobbied against emergency rules to protect their workers and pushed to speed up their lines, making it ever more difficult to maintain social distance on the shop floor. For their trouble, these companies brought home “record profits” during the pandemic, a September 2021 report from the National Economic Council found.

The power imbalance between capital and labor in meatpacking long predates the pandemic. These days, just four giant companies slaughter and pack more that half of the beef cattle, hogs, and chicken grown in the United States. As the industry has consolidated into fewer and bigger conglomerates, the workforce—largely made up of people of color, many of whom are immigrants—faced ever harsher conditions even as their real wages deteriorated. A 2016 Oxfam report found that in poultry plants, workers were forced to work so rapidly and relentlessly that they were “routinely” denied bathroom breaks and sometimes resorted to wearing diapers. Oxfam added:

Supervisors mock their needs and ignore their requests; they threaten punishment or firing. Workers wait inordinately long times (an hour or more), then race to accomplish the task within a certain timeframe (e.g., ten minutes) or risk discipline.

Then there’s the problem of repetitive stress injuries: conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome, triggered by performing the same motion over and over, like meatpacking workers do. Federal regulators haven’t done a comprehensive study of how common such maladies are within this workforce, but when they have looked, the results are chilling. Two studies of individual poultry plants by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a branch of the CDC, both found that more than a third of employees were working despite showing evidence of carpal tunnel syndrome along with high rates of other musculoskeletal maladies.

In the 1990s, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration attempted to roll out rules designed to protect workers from repetitive stress injuries. As I showed in a piece last year, management-side labor lawyer Eugene Scalia, whose father then served on the Supreme Court, led a lobbying push that, in 2001, crushed the protective rules, known as an “ergonomic standard.” (Scalia served as secretary of the Labor Department, which oversees OSHA, under President Donald Trump.)

Twenty years later—over which time Human Rights Watch saw fit to drop not one but two scathing reports on the industry’s working conditions—the recent Booker-Khanna bill, Protecting America’s Meatpacking Workers Act, would finally bring such standards to slaughterhouses. The bill directs OSHA to come up with an industrywide protocol for protecting workers from repetitive stress injuries after evaluating the hazards of each job on the line, with worker participation in the process. And it would establish remedies for hazards, including “rest breaks, equipment and workstation redesign, work pace reductions, or job rotation to less forceful or repetitive jobs.”

The bill would also crack down on abuse of employees around bathroom use, requiring, among other things, that OSHA leans on companies to “allow employees to leave their work stations to use a toilet facility when needed and without punishment,” and cut down on bathroom lines by providing enough toilets to match the size of the workforce.

Debbie Berkowitz, who served as a top OSHA official during the Obama administration and is now a fellow at Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor, called the bill “terrific,” adding that it “addresses many things that would significantly improve conditions in meat and poultry plants and would make a great impact on reducing injuries and illnesses and deaths.”

In addition to the long-delayed ergonomic standards, the bill “strengthens retaliation protections for workers who raise safety concerns and brings those protections.” And giving OSHA the tools and mandate to enforce safe conditions in meatpacking plants would mean a much greater degree of protection for them if and when another pandemic strikes—or if the current one flares up again—Berkowitz said.

The question, of course, is whether it stands a chance of passing in a Congress with slim Democratic majorities and members in both parties who make a principle of promoting corporate over worker interests. Ferd Hoefner, senior strategic adviser for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and a longtime Hill watcher, says the bill “does not stand a chance of passing,” but “nonetheless could result in some important, though less comprehensive, outcomes.”

As an example, he noted that a previous Booker-sponsored bill, the Justice for Black Farmers Act, never found traction in Washington—but an important piece of it, $4 billion in debt relief for farmers of color, ultimately made it into the American Rescue Plan Act that passed last March. (That relief now hangs in the balance after being successfully challenged in court by right-wing political operatives, a story I laid out here.) Given the steep challenges Democrats face in the 2022 midterms for preserving their majorities, the window for any pro-worker legislation is probably closing fast.

Unless Booker, Khanna, and co-sponsors Sens. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.), Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) make a big fuss and generate some legislative magic, the perilous conditions faced by the workers who process the nation’s meat supply will persist indefinitely.

Maybe President Joe Biden will pitch in to the effort by publicly pressuring Congress to pass it. Back in May 2020, candidate Biden vowed to stick up for meatpacking workers, declaring that “absolutely, positively, no worker’s life is worth me getting a cheaper hamburger. No worker’s life is worth that.”