One Saturday night, I saw a post in a Facebook group for my autoimmune disorder: Thanks to Dr. Brooke Goldner’s vegan smoothie diet, the poster said, she’d been able to stop all medicines for our shared chronic illness. Goldner, a practicing psychiatrist, has garnered a strong social media following, thriving book sales, and business success around an extraordinary claim: that she was able to “reverse” her own case of lupus, a painful autoimmune disorder with no known cure that impacts around 5 million people worldwide. With her guidance, she says, people with all kinds of autoimmune conditions and chronic illnesses can do the same.

It can take years for people with chronic illnesses to get the right diagnoses. Some, like myself, were told that our physical illnesses were the result of anxiety. I thought the symptoms of my own autoimmune disorder would go away after I learned what was making me sick. That has not been the case, and it took me a few years to accept. My medication helps keep my oxygen level above 95 percent, but I’m still exhausted every day.

Naturally, I wanted to learn more about Goldner’s “Goodbye Lupus” program.

Goldner claims that her expensive “nourishment” courses—whose participants pay thousands of dollars to consume, almost exclusively, vegan smoothies for four to six weeks—can not only put autoimmune disorders and other chronic illnesses in remission, but reverse them entirely. In her self-published books, three of which currently rank in Amazon’s top five “Best Sellers in Lupus,” Goldner claims she was able to stop all lupus medications by turning to her vegan dietary protocol. Participants in her six-week program are supposed to log everything they eat in a journal, which they submit to Goldner for feedback, and join weekly group meetings. They also receive daily motivational videos; if they sign up for the four-week one-on-one program (at nearly $6,000), they get a personal phone number to text Goldner for advice. After the course, people can continue with the smoothies and other plant-based meals, including a nice-sounding avocado and pumpkin seed pesto pasta.

Autoimmune disorders, in which the immune system mistakenly attacks itself, affect millions of people in the United States, including 1.5 million living with lupus. Especially because around 80 percent of people who have an autoimmune disorder are women, treating them hasn’t always been the focus of intense research—despite the possibility of severe, potentially fatal complications. In 2000, one study placed autoimmune disorders among the ten leading causes of death in the US for women under 65.

Without medical management, people with lupus risk organ failure or death. But those medications can come with frustrating side effects, even if they do treat its symptoms. That makes alternative medicine appealing. And Goldner is a member of the Forbes Health Advisory Board, which gives what she promotes some legitimacy in communities where pseudoscience—and skepticism—are common. The global health and wellness industry has a value of $4 trillion, so there’s a lot to gain with claims of radical cures. It’s not clear how much her courses bring in annually, but in 2021, Goldner bought a more than 9,000-square-foot mansion near Houston, valued at over $2 million —in one Instagram video, Goldner’s husband circles the property in a Ferrari, two more luxury cars stationed outside.

On their own, some of Goldner’s smoothies look pretty good, like her “daily drinker” of raw kale, spinach, chard, frozen bananas, mangoes, and flax seeds. Some of those ingredients can benefit the immune system, but no analysis of peer-reviewed studies exists to show that vegan smoothies are as helpful in managing symptoms as, for instance, hydroxychloroquine. And in 2020 guidelines for her six-week program, Goldner warns that participants could “experience detoxification symptoms such as dizziness, light-headedness, mild rashes or itching, mood swings, changes in sleep patterns, flu-like symptoms, or even temporary spikes in pain levels.” Those aren’t fun symptoms on top of being chronically ill.

Some people do find that certain foods trigger certain symptoms, which registered dieticians can help explore. But Goldner’s advice—in her paid courses, books, and free guidance online—raises a question: When it comes to what health professionals promote on social media, where’s the ethical line?

For evidence backing her lupus-reversal protocol, Goldner points to a case report she co-published in February in the well-respected journal Frontiers in Nutrition. Three people, according to that paper, were able to reduce symptoms of Sjögren’s syndrome and lupus after going on her protocol. It’s not clear how the three were selected, and such reports rarely include a control group—case reports on individual bad reactions to vaccines, for instance, are a favorite of anti-vaxxers—but the cases used were all people who had positive experiences. Goldner does, however, make it clear that she’s the owner of the business that developed and sells courses to people participating.

An Instagram post by Goldner announcing her Frontiers publication.

In a phone call, Goldner told me she’d been approached about clinical trials by companies she’s “not going to name.” She has been hesitant, she said, because she wouldn’t be involved enough to make sure her protocol was implemented correctly. Goldner also said she wasn’t “anti-medication”—if, despite her diet, abnormal blood test results meant she had to go back on lupus medication, she would—but encourages people to talk to their doctors about dropping medications or cutting dosages if their health improves on her protocol. (Beyond adjusting their diets, Goldner writes in one of her books, people need to find the motivation to get better: “without it, you’re likely to be focused on what’s going on in your body; the daily aches and pains and struggles.”)

In a 2020 interview with a Texas local TV station, Goldner gave advice for limiting immune response to Covid-19—to not drink alcohol or eat delivery food—in her capacity as a self-proclaimed “autoimmune disease reversal expert.” Together with her MD, it’s a framing that could lead people to believe Goldner is a rheumatologist, a specialist physician who treats autoimmune disorders. Goldner also told me she was the sole autoimmune professor for an online nutrition certificate program run by Cornell University. Natasha Lantz, the executive director of Cornell’s T. Colin Campbell Center for Nutrition Studies, said in an email that Goldner is a featured expert for one class, where a video of her giving one lecture is reused. Featured experts do not have a continuing relationship with the program or its instructors, Lantz says, but Goldner did also receive a plant-based nutrition certificate from the center.

When I went to Goldner’s website, I found a disclaimer at the bottom that neither she nor anyone else associated with Goodbye Lupus “has, is, or will practice medicine with clients,” that they “limit their services strictly to guiding clients through a hyper-nutritious diet program,” and that any prescription changes would be left to a person’s doctor. Participants in her online programs sign a contract saying that they will “not contact Dr. Goldner for medical advice or treatment of any kind” and acknowledge that Goldner isn’t their doctor. Lisa Parker, a bioethicist and director of the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Bioethics and Health Law, reviewed some materials on Goodbye Lupus at my request; she says those disclaimers could reflect “the difference between how the Food and Drug Administration regulates food, dietary supplements on the one hand, and medicine on the other”—in other words, it’s safer to make extraordinary medical claims with a disclaimer about not practicing medicine.

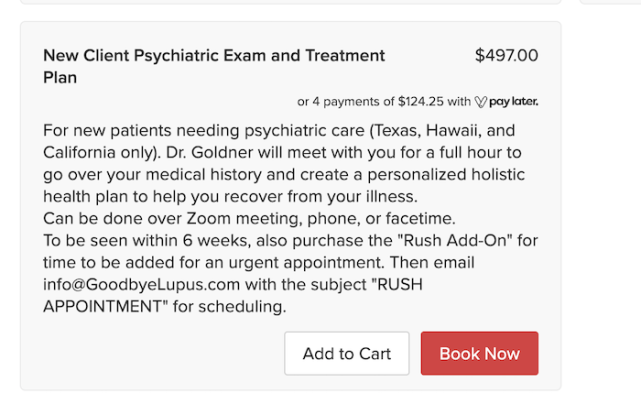

People can also sign up for one-on-one wellness coaching with Goldner on a separate platform, where she helps them “create a personalized recovery plan” based on diet. Or you can enroll in slightly cheaper sessions with Goldner’s husband, Goodbye Lupus co-founder Thomas Tadlock, who markets himself as a weight-loss expert. But there are also options to sign up for psychiatric appointments with Goldner by emailing a GoodbyeLupus.com address, open to patients in the three states where she’s licensed to practice psychiatry:

Goldner’s psychiatric appointment booking page.

But doesn’t Goldner claim not to give Goodbye Lupus clients “medical advice or treatment of any kind”?

Goldner says she doesn’t see psychiatric patients through Goodbye Lupus—she just tells them to use her Goodbye Lupus email to set up the visits. Parker, the bioethicist, had questions. “If she’s not willing to make recommendations about medication, then it is an unusual kind of psychiatry appointment,” Parker told me. Goldner acknowledged to me that she does prescribe some medication to people she sees as a psychiatrist, but said she takes a holistic approach.

Outside of her nourishment courses and one-on-one sessions, people can still get free advice from Goldner on social media—like in the Facebook group Smoothie Shred, another joint project of Goldner and her husband, which has over 60,000 members. Both on her Facebook page and in the group, Goldner hosts live video calls where she gives health advice. She occasionally responds to comments in the group, like a post asking about iodine supplements for Hashimoto’s disease, an autoimmune disorder that affects the thyroid. Goldner, who has spoken positively about iodine supplements, responded, “My recommendation is to follow my recommendation.” That may work for some people; it also sounds like medical advice.

“There are potential interactions between dietary supplements and medication, or even diet and medication,” Parker said, which doesn’t make such advice completely harmless. Iodine can interact with common medications like lithium to decrease thyroid function, which could make Hashimoto’s disease worse. Spinach, which Goldner recommends adding to her green smoothies, has a negative interaction with warfarin, a drug used to prevent blood clots from forming. The list goes on.

Goldner says she’s clear that she is not acting as anyone’s doctor when she gives online advice—though some people, she said, see her “like a mother.” She likens jumping into her advice without talking to a doctor to doing the same after watching celebrity physicians like Dr. Oz.

As a successful health influencer, Goldner has her supporters—who not only cheer her on social media, but also end up giving advice of their own. It’s not unusual in chronic illness groups for people to share their lived experiences and what’s helped them; it’s different when they’re doing so in support of a psychiatrist who says she can reverse incurable diseases like multiple sclerosis and diabetes. In a post that Goldner didn’t respond to, members of her Smoothie Shred group advised a poster’s sister with dementia to go off certain medications in favor of a raw food diet. (Starting vegan diets can also be dangerous for someone with dementia if they’re no longer getting the right nutrients.)

In an email, Dr. Asha Shajahan, the co-creator of MisinfoRx, a toolkit to help health care providers combat medical misinformation, said “any glimmer of hope will be attractive” for people who may be in denial about the chronic nature of an illness, “or anything that confirms their belief that they are not ill and can be cured.” In particular, Shajahan says, “personal stories and anecdotes from others who claim to have found relief from chronic illness symptoms through unconventional treatments can be compelling.”

The most notorious claim that a proprietary diet healed an incurable illness was that of Belle Gibson, a wellness blogger who, while promoting her Whole Pantry recipe app from 2013 to 2015, said her diet cured her brain cancer, a condition she never had (there is nothing to suggest Goldner isn’t honest about having lupus). Gibson’s story shows just how much people trust patient voices, let alone credentialed medical professionals—even when it leads them down a dangerous path.

Goldner seems to realize the power of a personal story, her own or otherwise. On her Instagram, she shares many testimonials on how people have said “goodbye” to neuromyelitis optica, ADHD, Sjögren’s syndrome, and other incurable conditions through her courses and books. She also seems to realize that Goodbye Lupus is a business, and that it owes some of its success to people’s trust in medical experts. “[Goldner] probably would not even say that they’re patients,” Parker said, “but they are at least clients, or they are customers who are entering into a trusting relationship with her because she is saying she’s a healthcare professional.”