Last night I read a couple of articles about a new bipartisan Medicare proposal cosponsored by Rep. Paul Ryan and Sen. Ron Wyden. However, the details were vague enough that I decided to wait until today to write about it.

So here it is: a 12-page white paper explaining the plan. (Though, tellingly, only six pages are dedicated to the plan itself.) A shorter summary, coauthored by Ryan and Wyden, is in the Wall Street Journal today.

Overall, it doesn’t sound too bad. It has the usual unfortunate dodge of grandfathering everyone older than 55 into the current system, but I’m willing to concede that  this is probably politically necessary. It caps Medicare growth at GDP+1%, the same goal as Obamacare. It institutes means testing, charging lower premiums to low-income seniors and higher premiums to high-income seniors. And it features an out-of-pocket cap to protect seniors from catastrophic costs.

this is probably politically necessary. It caps Medicare growth at GDP+1%, the same goal as Obamacare. It institutes means testing, charging lower premiums to low-income seniors and higher premiums to high-income seniors. And it features an out-of-pocket cap to protect seniors from catastrophic costs.

None of this is especially new. What is new is their proposal to create a national exchange for Medicare providers. Basically, the federal government would set a minimum benefit level, and everyone who wants to provide Medicare services, including the traditional government-run Medicare program, would enter a bid:

The second-least expensive approved plan or fee-for-service Medicare, whichever is least expensive, would establish the benchmark that determines the coverage-support amount for the plan chosen by the senior. If a senior chose a costlier plan than the benchmark, he or she would be responsible for paying the difference. Conversely, if that senior chose a plan that cost less than the benchmark, he or she would be given a rebate for the difference. Payments to plans would be risk-adjusted and geographically rated. Private health plans would be required to cover at least the actuarial equivalent of the benefit package provided by fee-for-service Medicare.

This is similar to Obamacare in a lot of ways. In fact, the entire Wyden-Ryan plan goes a long way toward making Medicare similar to Obamacare. Basically, Obamacare moves our current private insurance system in the direction of government support with competitive bidding, while Wyden-Ryan moves our current federal Medicare system in the direction of private support with competitive bidding. Somewhere in the middle they meet, and our entire healthcare system becomes a fairly homogeneous blend of public and private, similar in some ways to the systems in Switzerland or the Netherlands. Yuval Levin makes this point explicitly here, and as a conservative he’s not especially happy that this is where we could end up. But done right, it wouldn’t necessarily be a bad place to be.

At the same time, the Wyden-Ryan plan is still vague enough that it’s impossible to say anything firm about it. There are just too many open questions, many of which Austin Frakt outlines here. But competitive bidding, done right, could rein in cost growth somewhat, and it’s not something liberals should automatically oppose. The real question is whether it will have a substantial effect. Jon Cohn doesn’t think so:

Some advocates for premium support claim it would save money because private plans are inherently more innovative and efficient than old-fashioned, government-run Medicare. Not to be blunt, but the evidence for this is non-existent: Medicare has lower overhead, enormous economies of scale, and the ability to keep down costs by dictating prices to the providers of care. (Conservatives may not like that last part, but purely in terms of lowering prices it’s quite effective.)

In the end, the heavy lifting on cost control will most likely be done by the GDP+1% cost cap. This is not an inherently ridiculous cap, like the one in Ryan’s earlier plans, and Ryan and Wyden also claim it would work differently than other caps:

Unlike other proposals, spending that exceeds the cap would neither be addressed through bureaucratic cuts nor passed on to seniors by default as higher premiums. Instead, Congress would be required to do its job: Determine why the costs exceeded the cap and—when the evidence merits—reduce payments to providers, drug companies, or others who may be responsible for escalating costs.

I get nervous anytime a plan relies on “Congress doing its job,” but obviously this is the kind of detail that would end up getting completely transformed anyway if the Wyden-Ryan plan ever made it through the legislative sausage grinder. So there’s not much point in getting too worked up about it.

Bottom line: this isn’t necessarily a bad plan. Unfortunately, it’s also not clear if it’s really a very effective plan either. But I’d certainly put it into the broad bucket of plans that are reasonable starting points for conversation. Given Paul Ryan’s immense credibility with the tea party wing of the Republican Party, it’s significant that he’s put his name to this. It’s worth a conversation.

tax rates by either taking lower-paying jobs than they could, or working less — not in every individual case, but in aggregate.

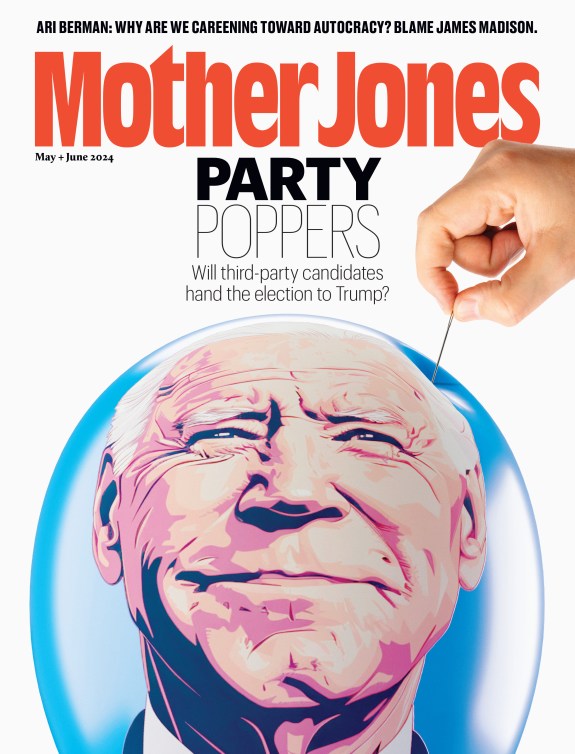

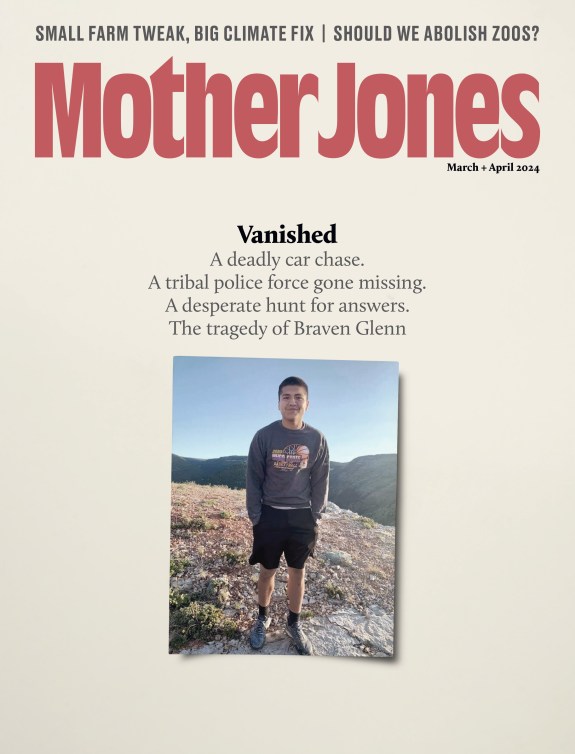

out there on the front lines, producing first-person accounts of the stories that progressives care about most.

out there on the front lines, producing first-person accounts of the stories that progressives care about most.

this is probably politically necessary. It caps Medicare growth at GDP+1%, the same goal as Obamacare. It institutes means testing, charging lower premiums to low-income seniors and higher premiums to high-income seniors. And it features an out-of-pocket cap to protect seniors from catastrophic costs.

this is probably politically necessary. It caps Medicare growth at GDP+1%, the same goal as Obamacare. It institutes means testing, charging lower premiums to low-income seniors and higher premiums to high-income seniors. And it features an out-of-pocket cap to protect seniors from catastrophic costs.