Brad Plumer takes a look today at recent research on overfishing:

Brad Plumer takes a look today at recent research on overfishing:

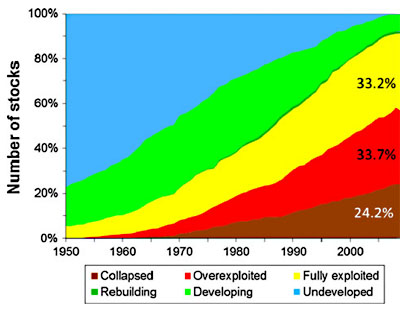

Ideally, we’d have in-depth stock assessments for the entire world, but those are difficult, expensive, and fairly rare. So, in their paper, Pitcher and Cheung review a number of recent studies that use indirect measurements instead. For example, they note that recent analyses of fish catches suggest that about 58 percent of the world’s fish stocks have now collapsed or are overexploited.

Note that 91 percent of all fish stocks today are either fully exploited or overexploited. There are some success stories of fish stocks being rebuilt, but that’s the almost invisible dark green line near the top. It represents less than 1 percent of all global fish stocks.

But all is not lost. Most of these success stories are in advanced economies, including the U.S., Australia, Canada, and Norway, which is exactly where you’d expect progress to begin. Low-income countries lag behind, but that may change as the success stories start to percolate downward:

Yet many low-income countries lack the resources to monitor their fisheries. And even richer nations struggle to enforce the laws they have: In Europe, regulators have consistently set lax fishing quotas — in part due to lobbying from the fishing industry. (“Europe is not one of the places that’s doing well,” says Pitcher, “with a few exceptions like Norway.”) Meanwhile, as climate change warms the ocean and disrupts ecosystems in unpredictable ways, regulating fisheries may become even more difficult.

“Attempts to remedy the situation need to be urgent, focused, innovative, and global,” the paper concludes. But that’s harder than it sounds.

Yes it is.