"Downfall," everyone's favorite canvas for subtitle humor.

On Monday morning I wrote my most controversial and reviled post of the year so far. The subject was subtitles in movies. Perhaps, I suggested, they are not the greatest thing since sliced bread.

Subtitles! Does this strike you as an odd topic to generate a huge Twitter storm? If so, it just shows that you don’t know Twitter very well. Of course people went nuts over it. It’s Twitter! A couple of people decided they didn’t like what I said, and a mob followed in their wake.

Normally I just get a laugh out of this stuff. The tweets are mostly from the same gang of folks who despise me already and don’t really care what the latest two-minutes hate is about. But a few of the comments were offered in good faith, and they got me curious. Before I get to that, though, here’s a short clarification of my position on movie subtitles:

Do you, Kevin Drum, hate subtitles?

No, not at all. More on that later.

Then you must hate the hearing impaired?

Nope. I myself am mildly hearing impaired and always watch movies on TV with closed captioning on. But my post was about subtitles (i.e., words that are translations from the spoken language of a film), not closed captioning (i.e., words in the same language as the film, primarily meant as hearing assistance). They are different things.

Then you must be racist. Why do you hate foreign films? Why do you hate Korea? Why do you hate Parasite?

Don’t be ridiculous.

You said you didn’t see any movies last year. But if you know nothing about movies, why even weigh in on this?

It’s true that I went to very few theatrical releases last year. Partly this is because I just didn’t, and partly it’s because my moviegoing has been severely curtailed since I got cancer. (Generally speaking, it’s good to avoid crowded, germy places when your immune system is compromised.) However, this doesn’t mean that I’ve never seen any movies and know nothing about them. Nor does it mean that I never watch movies on TV.

Your father was a film scholar! Your parents wrote a biography of Carl Th. Dreyer! How could you?

This is true, and my father, if he were alive, would be the first to defend subtitles. However, my father was also good at reading comprehension, so he probably wouldn’t have been upset at my brief little post.

Why not?

Because I didn’t say that subtitles are bad in an absolute sense. I said that subtitles detract from the theatrical experience and there are legitimate reasons to dislike them. This seems obvious: if possible, everyone would prefer to watch movies made in their native tongue. This is because subtitles distract from the cinematography; take a long time to read for some people; don’t replicate the vocal nuances of the spoken voice; and never perfectly capture the words written by the screenwriter and spoken by the actors. We need subtitles if we want to watch foreign language films, but that doesn’t mean we have to deny that they do indeed have drawbacks.

This really should be all I need to say, but it turns out that many people got upset by a collateral point I made: that everyone hates subtitles and it’s faux sophistication to pretend that no one should have a problem with them. So let’s address that.

First off, “everyone hates subtitles” was, I thought, humorous hyperbole. I meant that most people dislike subtitles. What’s more, the context was my annoyance at Alissa Wilkinson saying that “Americans just don’t like reading subtitles,” a derisive attitude that’s uncalled for since in fact it’s a very global phenomenon.

But is even this true? Do most people around the world dislike subtitles? This is not really a provable statement, but I think the evidence certainly points strongly in that direction. What follows is a bit scattered, but should be enough to persuade you that, indeed, “most people dislike subtitles.”

Let’s start at the start: When sound was added to movies, intertitles went away almost instantly all over the world. Plainly, people preferred to listen to human conversation instead of reading dialogue on the screen.

Next: Anyone of my age who’s traveled a lot has seen the changes in film translation in Europe since the ’70s. In the past, an American could turn on a TV in Europe and find quite a bit of English-language content because most imported shows were subtitled American productions. Over time, that went away. There were more shows produced locally, and the remaining American shows were mostly dubbed. Subtitles slowly but steadily disappeared.

More recently, Monday’s subtitle Twitter storm was kicked off by the fact that Parasite was the first subtitled movie to win Best Picture and that, more generally, subtitled movies have long had difficulty gaining large audiences in America. This certainly suggests something pretty similar to “most people dislike subtitles.”

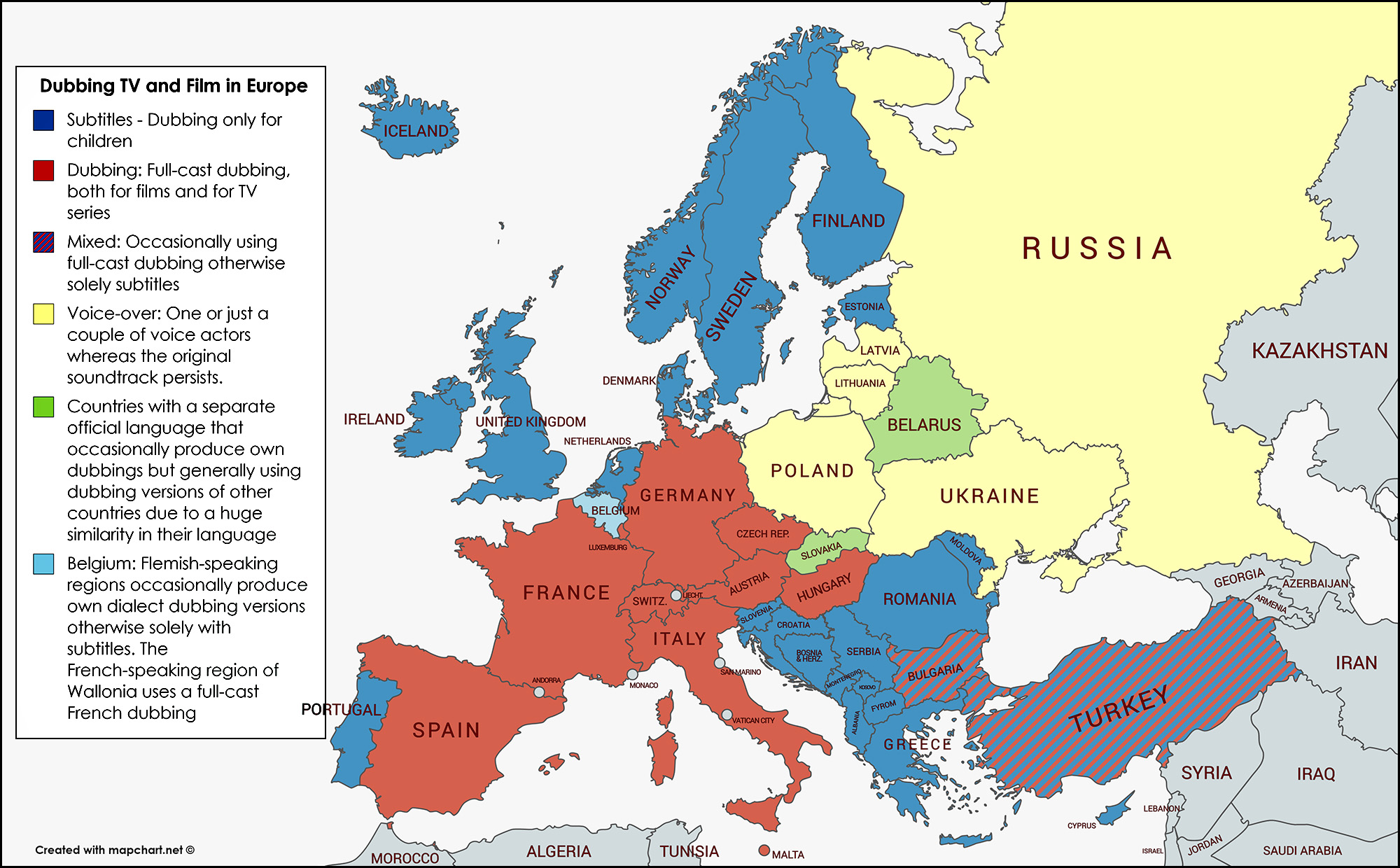

But different countries have evolved different preferences. Germany, France, Italy, and Japan, for example, are “dubbing countries,” meaning that dubbing is popular with theater audiences. The Nordic countries, by contrast, are “subtitle countries.” But even there nuances abound. In France, for example, Hollywood blockbusters are always dubbed, while smaller, less popular films are usually subtitled.

Why? Mostly it’s because dubbing is expensive, which means it’s only practical in countries with a fairly large movie market. Generally speaking, dubbing is common in large, rich countries, while subtitles are common in smaller, poorer countries. This suggests that subtitles are mostly used only where there’s no choice. They start to fade away as countries become richer and develop a large, mass movie market that can support the cost of doing voiceovers instead.

But there are exceptions. China, for example, started out as a dubbing country, even though it was very poor, for reasons related to literacy rates, political dictates, and a desire to standardize Mandarin—although this is changing as China continues to develop its own movie industry. Spanish-speaking countries, regardless of how rich they are, have long been dubbing countries and still are, for reasons that are unclear. Conversely, the United States, the richest country of all, has always been a subtitle country (albeit one with a very limited appetite for foreign films).

All this said, there are also demographic differences between those who like subtitles and those who don’t—and this is true all over the world. This gets us into delicate territory. Sandra Vega explains things this way: “Popular classes prefer the dub, the sense of immediacy and ease in understanding, enjoyment effortlessly.” Put more bluntly, we intellectual types prefer subtitles. The unwashed masses prefer dubbed movies. More on this shortly.

Even rich, English-speaking countries can switch away from subtitles if people are given the opportunity. Great Britain, for example, is historically a subtitle country, but Miguel Mera tells the following story: “In 1987 the United Kingdom’s Channel 4 questioned the idea of a single dominant form by broadcasting twenty-six episodes of the French soap opera Châteauvallon twice weekly, once with subtitles and once in a dubbed version. This was the first time in the history of British television that such a long foreign language series had been shown and that a programme was transmitted with a choice of the language transfer method. The audience response to this experiment was gauged and the results were fascinating and completely unexpected. In a country that generally looks down on dubbing as being inferior, a significant preference was shown in all age groups for the re-voiced version.”

You should not be surprised to learn that in countries with a long tradition of dubbing, they’ve gotten very good at it. If you’re thinking about the kind of comical dubbing you hear in old Japanese Godzilla movies, think again. Because dubbing is uncommon in the US, most Americans are way behind the times on what the technology is like and haven’t bothered to learn anything new about it since the 1960s. But in many dubbing countries, lip syncing and voice acting have gotten very sophisticated, and the voice actors who do the dubbing have become well-known names.¹

Even in America, where our position as the world’s pre-eminent moviemaker has meant that we don’t have to tolerate foreign-language movies in any form, dubbing is becoming more popular as streaming companies start to buy up more foreign content. Netflix has been dubbing like crazy over the past few years. Why? Because their research shows that “dubbed versions of hit shows are more popular than their subtitled equivalents.” For example, “the German drama Dark was watched in its dubbed version by 81 percent of audiences in English-speaking countries.”

My main message here is: (1) Don’t be parochial. America is generally a subtitle country, and most of my readers are pretty educated folks. Of course you prefer subtitles! You’re a product of your culture just like everyone else. That’s probably also why I personally prefer subtitles most of the time. (2) Don’t be classist. People who aren’t film buffs generally prefer their Hollywood blockbusters to be dubbed, and that’s a perfectly defensible choice. Stop sneering at them because they don’t read as rapidly and fluently as you do.² (3) Don’t be stuck in the past. The technology of dubbing as an alternative to subtitles has changed a lot over the past couple of decades. (4) Don’t ignorantly sing the praises of subtitles. They are a necessary evil, not a sacred cow. A true film buff understands the pros and cons of both subtitles and dubbing and feels no need to pretend that subtitles are faultless. (5) Don’t be racist. Lots of movie audiences in brown-majority countries prefer dubbed movies over subtitles. Your preferences are no better than theirs.

And that’s that. Civil conversation about this is welcome, either in comments or on Twitter.

¹Here’s an excerpt from a Hollywood Reporter piece: “Christian Bruckner — the actor whose deep rumbling bass has been synonymous with Robert De Niro in Germany for nearly 40 years — has become a star in his own right, using his aural connection to the two-time Oscar winner to build a successful career in commercials and audio books….Across the globe, other voice-over stars have emerged. Spain’s Constantino Romero has given voice to Clint Eastwood for decades. In Japan, Koichi Yamadera is the go-to voice for pretty much every big African-American star from Eddie Murphy and Denzel Washington to Will Smith. Not wanting to become typecast, Yamadera also has provided the Japanese voice for Charlie Sheen, Jim Carrey, Brad Pitt and Tom Hanks. The prolific dubber recently pulled off an impressive double play, providing the voice for Don Draper in the Japanese version of Mad Men and Walter White for Breaking Bad.”

And another from The National: “Deeny Kaplan, executive vice president of Miami dubbing house The Kitchen, describes the process as painstaking work, going from breaking down the original script by syllable and delivering a translation in a metre and structure as close as possible to the original. Actors are used who have carefully studied the tone and tempo of the original speech, with intricate time coding also a feature of the process, while video is slowed down or sped up to correctly lip sync speech on occasions when an appropriate translation can’t help by itself. The key to a successful dub, she says, lies in ‘using native speakers, correct casting and proper adaption’. ‘There’s no room for mistakes today,’ she says. ‘You have several levels of quality checks, for everything from sound checks to music and mixing. All of it is scrutinised.’ ”

²Plus there are way more of them than you. This is why it’s safe to say that “most” people don’t like subtitles. The number of highly-educated film buffs may seem large on Twitter, but in real life there just aren’t that many of them.